Spinal fusion surgery is a medical procedure designed to address issues involving the vertebrae, the small bones that form the spinal column. The process essentially involves “welding” two or more vertebrae to fuse into a single, solid bone. This fusion helps to eliminate painful motion between vertebrae or to provide added stability to the spine.

Typically, spine surgery is advised only after a doctor has identified the precise cause of a patient’s discomfort. Diagnostic imaging techniques such as X-rays, CT scans, and MRIs are often used to confirm the source of pain before recommending spinal fusion.

Spinal fusion surgery can be effective for treating several back issues, including:

- Degenerative disc disease

- Spondylolisthesis

- Spinal stenosis

- Scoliosis

- Vertebral fractures

- Infections

- Herniated discs

- Spinal tumors

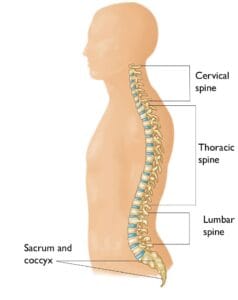

Gaining a basic understanding of spinal anatomy can be beneficial in learning more about spinal fusion and its purpose. For more insights into how your spine functions, see: Spine Basics.

Spinal fusion can be performed in any region of the spine.

Description

Spinal fusion surgery aims to reduce movement between vertebrae, helping to alleviate pain by preventing the stretching of surrounding nerves, muscles, and ligaments. This procedure is recommended when movement itself is a source of discomfort, particularly in cases of arthritis, instability due to injury, degenerative disease, or natural aging. The concept is that if the affected vertebrae no longer move, they should no longer cause pain.

For patients experiencing leg or arm pain along with back pain, a decompression surgery (laminectomy) may be performed alongside spinal fusion. This procedure removes bone and diseased tissue that press on spinal nerves.

While spinal fusion may limit some spinal flexibility, most fusions involve small segments of the spine, and many patients notice minimal or no impact on their range of motion. Your surgeon will discuss whether the specific procedure may affect your spinal flexibility or motion.

Procedure

Spinal fusion in the lumbar (lower back) and cervical (neck) regions has been a standard procedure for decades. Surgeons may use various fusion techniques and approaches depending on the location and nature of the condition.

For an anterior approach, the surgeon accesses the spine through an incision in the lower abdomen (for lumbar fusion) or the front of the neck (for cervical fusion). For a posterior approach, the incision is made in the back. In a lateral approach, the surgeon reaches the spine from the side.

Minimally invasive techniques are also available, allowing for smaller incisions and reduced recovery times. The optimal procedure will depend on your condition and the spine area involved.

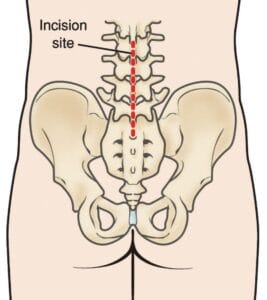

In a posterior approach to lumbar surgery, an incision is made down the middle of the lower back, over the vertebrae to be fused.

Bone Grafting

Bone grafting is essential in spinal fusion surgery to promote healing and fusion between vertebrae. Small bone fragments are typically placed between the vertebrae to stimulate bone growth and facilitate solid fusion. Sometimes, larger bone sections are used to provide structural support.

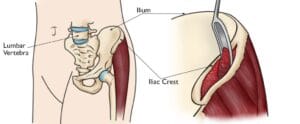

Most autografts are harvested from an area of the pelvis called the “iliac crest.”

Historically, bone grafts were taken from the patient’s pelvis in a procedure called autografting, which required an additional incision and could increase post-surgery pain. In cases where decompression is also performed, the surgeon may use bone removed during decompression as a local autograft, essentially “recycling” the bone to promote fusion.

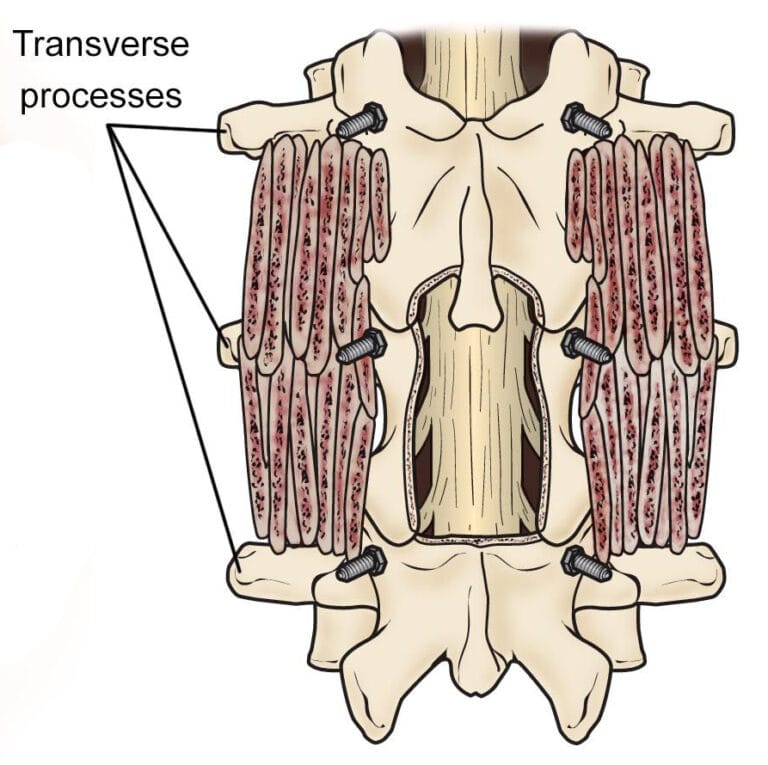

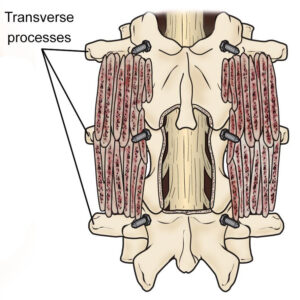

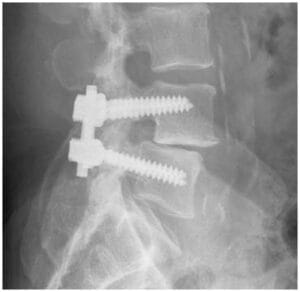

Illustration of a posterolateral lumbar fusion (PLF) shows bone graft material placed over the transverse processes of the vertebrae. Screws have been placed to provide stability to the spine while the fusion heals.

Other grafting options include allografts, sourced from cadaver bones, and processed through bone banks to ensure safety. There are also synthetic bone graft materials available:

- Demineralized Bone Matrices (DBMs): Created from cadaver bones with calcium removed, DBMs can take on a putty or gel consistency and are often combined with other grafts.

- Bone Morphogenetic Proteins (BMPs): These synthetic proteins stimulate bone growth, offering a powerful alternative to autografts in certain cases.

- Synthetic Bone: Often referred to as “ceramics,” synthetic bone grafts are made from calcium phosphate, mimicking the shape and consistency of natural bone.

Your surgeon will discuss which bone graft material best suits your condition and procedure.

(Left) This X-ray of the lumbar spine shows decreased disk space between the vertebrae. (Right) In an anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF), a metallic interbody cage has been inserted to restore the normal height of the disk space. The bone graft is contained within the cage and cannot be seen on X-ray.

Immobilization

After bone grafting, it’s essential to keep the vertebrae stable to support proper fusion. In most cases, surgeons use plates, screws, and rods to secure the spine in place, a technique known as internal fixation. This added stability often enhances the success rate of the fusion and allows many patients to begin moving sooner after surgery. Your surgeon may also recommend wearing a brace to protect the fusion site and support the healing process.

In this X-ray of posterolateral lumbar fusion (PLF), a rod and screws have been used to prevent motion at the spinal segments being fused.

Complications

Like any surgical procedure, spinal fusion carries certain risks. Your doctor will review these risks with you prior to the surgery and take preventive measures to minimize complications. Possible risks include:

- Infection: Antibiotics are administered before, during, and often after surgery to reduce infection risk.

- Bleeding: Some blood loss is normal, though typically minimal, so pre-surgery blood donation is usually unnecessary.

- Pain at Graft Site: A small number of patients experience ongoing discomfort at the bone graft site.

- Recurring Symptoms: In some cases, original symptoms may return. If this occurs, notify your doctor for further evaluation.

- Pseudarthrosis: This condition occurs when the bone does not fully fuse. Smoking, diabetes, advanced age, and premature movement post-surgery can increase the risk. Additional surgery may be required in such cases.

- Nerve Damage: Although rare, nerve or blood vessel injuries can happen during surgery.

- Blood Clots: Although uncommon, blood clots in the legs can be dangerous if they travel to the lungs.

Warning Signs

It’s essential to monitor for blood clots and infection following surgery, especially in the first few weeks.

- Blood Clots: Signs include calf, ankle, or foot swelling, tenderness, or pain, and redness. If a clot travels to the lungs, it can cause chest pain, shortness of breath, or coughing. Seek emergency help if these occur.

- Infection: Infection post-spinal surgery is rare, but possible signs include redness, swelling, persistent wound drainage, pain, chills, and a fever over 101°F. Immediate medical attention is necessary if these symptoms arise.

Recovery

Pain Management

Postoperative pain is expected as part of recovery, and your medical team will work to manage it for faster healing. A variety of medications, sometimes in combination, may be prescribed to manage pain while minimizing opioid use. Opioids, though effective, carry risks of dependency and overdose. Take them only as prescribed and discontinue use as soon as possible once pain subsides. If pain persists or if you were on narcotics pre-surgery, discuss your pain management plan with your surgeon.

Rehabilitation

Bone fusion is a gradual process, often requiring several months for complete solidification, though comfort typically improves more quickly. During healing, it’s critical to maintain proper spinal alignment. You will learn proper techniques for moving, sitting, standing, and walking to aid recovery. Initially, light activities, such as walking, are recommended. As strength returns, activity levels can gradually increase, and physical therapy may begin between 6 weeks and 3 months post-surgery, based on your surgeon’s recommendation.

Following your doctor’s guidance and maintaining a healthy lifestyle will support a successful recovery.

Research

Ongoing research is focused on alternative bone graft materials that offer safe and effective substitutes for patient tissue. Additionally, total disc replacements and motion-preserving techniques are emerging as alternatives to spinal fusion for certain conditions. New biological therapies are also being developed to prevent disc degeneration and related nerve compression.