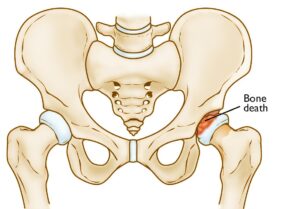

Perthes disease is a rare hip condition that primarily affects children. It develops when the blood supply to the femoral head—the rounded top of the thighbone—is temporarily interrupted. This lack of blood flow leads to the death of bone cells, a condition known as avascular necrosis.

Despite being called a “disease,” Perthes is better understood as a multi-stage condition that unfolds over several years. Initially, the femoral head weakens and begins to lose its shape due to the lack of nourishment. As the condition progresses, the bone may collapse. Eventually, blood flow to the affected area is restored, and the bone starts to regenerate and regain its structure.

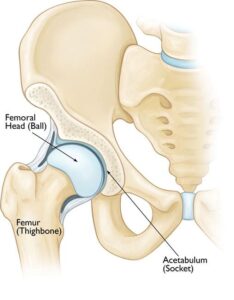

The goal of Perthes disease treatment is to encourage the regrowth of the femoral head into a rounded shape that fits properly within the acetabulum, the socket of the hip joint. Achieving this alignment helps maintain normal hip movement and reduces the risk of future complications, such as arthritis.

In most cases, the long-term outlook for children with Perthes disease is positive. With appropriate treatment, which typically spans 18 to 24 months, the majority of children resume normal activities without significant restrictions.

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint. The rounded head of the femur easily fits into the cup-shaped acetabulum to allow for a wide range of motion.

Overview

Perthes disease, also called Legg-Calvé-Perthes, is named after the three physicians who first identified and described the condition. It primarily affects children between the ages of 4 and 10 and is significantly more common in boys, who are five times more likely to develop the condition than girls. Both hips are involved in about 10% to 15% of cases, though this is less common.

Stages of Perthes Disease

Perthes disease progresses through four distinct stages, each marked by specific changes in the femoral head and its surrounding structures:

- Initial Stage (Necrosis):

During this stage, the blood supply to the femoral head is disrupted, causing bone cells in the area to die. This leads to inflammation and irritation, which may manifest as a limp or changes in walking patterns. The necrosis stage typically lasts for several months. - Fragmentation Stage:

Over the next 1 to 2 years, the body begins removing the dead bone beneath the articular cartilage and replacing it with new, softer bone. At this stage, the femoral head is fragile and prone to flattening or collapsing, often appearing fragmented or in pieces on imaging studies. - Reossification Stage:

In this phase, stronger new bone starts to form, giving shape to the femoral head. The reossification stage is the longest, potentially lasting several years as the bone continues to develop. - Healing Stage:

By this stage, bone regeneration is complete, and the femoral head reaches its final shape. The degree to which the femoral head retains its roundness depends on several factors, including:- The extent of damage sustained during the fragmentation phase.

- The child’s age when the condition began, as younger children have greater potential for bone regrowth and remodeling.

By addressing these stages through timely intervention, medical care aims to support proper bone development and minimize long-term complications.

In the first stage of Perthes disease, the bone in the head of the femur slowly dies.

Causes of Perthes Disease

The exact cause of Perthes disease remains unclear. However, recent research suggests there may be a genetic component influencing its development. Despite this potential link, more studies are needed to establish a definitive connection and understand the underlying mechanisms.

Symptoms of Perthes Disease

One of the earliest indicators of Perthes disease is a noticeable change in your child’s walking or running patterns, often becoming evident during physical activities such as sports. These changes may include limping, reduced range of motion, or an unusual running style, all caused by irritation in the hip joint.

Additional common symptoms include:

- Pain: This may be felt in the hip or groin and can also manifest in other areas like the thigh or knee due to referred pain.

- Activity-Related Discomfort: Pain typically intensifies during physical activity and subsides with rest.

- Muscle Spasms: Painful spasms around the hip may occur due to joint irritation.

Symptoms can vary based on your child’s activity levels and may appear intermittently, sometimes persisting for weeks or months before prompting a visit to a healthcare provider. Early recognition and diagnosis are critical for effective treatment and management of the condition.

Doctor Examination for Perthes Disease

To accurately diagnose Perthes disease, your child’s doctor will start by discussing their symptoms and medical history, followed by a detailed physical examination and imaging studies.

Physical Examination

During the examination, the doctor will evaluate the hip’s range of motion, as Perthes disease commonly restricts certain movements, including:

- Abduction: Moving the leg away from the body.

- Internal Rotation: Twisting the leg inward toward the body.

These limitations in movement often provide key clues for diagnosis.

X-rays

X-ray imaging is essential for confirming Perthes disease and understanding the extent of the condition. X-rays create detailed images of dense structures like bones, allowing the doctor to evaluate the health of the femoral head and determine the disease’s stage.

Children with Perthes disease will typically undergo multiple X-rays throughout their treatment, which may span two years or longer. It’s important to note that X-ray findings may initially show worsening of the condition before signs of gradual improvement become evident over time.

This comprehensive approach ensures accurate diagnosis and effective monitoring of the disease’s progression and response to treatment.

In this X-ray, Perthes disease has progressed to a collapse of the bone in the femoral head (arrow). The other side is normal.

In this X-ray, Perthes disease has progressed to a collapse of the bone in the femoral head (arrow). The other side is normal.

Treatment for Perthes Disease

The primary goals of Perthes disease treatment are to alleviate pain, maintain the round shape of the femoral head, and restore normal hip movement. Without proper treatment, the femoral head may become deformed and fail to fit properly within the acetabulum (hip socket). This misalignment can result in long-term complications, such as early-onset arthritis in adulthood.

Treatment plans are tailored to each child, with key factors influencing the approach, including:

- Age: Younger children (under 6 years old) have a higher capacity for femoral head regrowth and reshaping.

- Extent of damage: If more than 50% of the femoral head is affected by necrosis, the chances of regrowth without deformity are reduced.

- Stage of the disease: The progression of the condition at the time of diagnosis impacts the treatment options recommended.

Nonsurgical Treatment Options

Observation

For young children (ages 2 to 6) with minimal changes visible on initial X-rays, observation is often the preferred approach. Regular X-rays are used to monitor the healing and ensure the femoral head is regenerating properly as the disease progresses.

Anti-inflammatory Medications

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen, help reduce inflammation and alleviate pain caused by hip joint irritation. Your child’s doctor may recommend these medications for several months, adjusting the dosage as necessary throughout the disease stages.

Activity Modification

To protect the femoral head and reduce pain, high-impact activities such as running and jumping should be avoided. Crutches or a walker may be recommended to minimize weight-bearing on the affected hip.

Physical Therapy

Hip stiffness is a common symptom of Perthes disease. Physical therapy exercises are designed to restore the hip joint’s range of motion, with a focus on:

- Hip abduction: The child lies on their back with knees bent and feet flat, pushing their knees outward and then squeezing them together. A caregiver can assist by placing their hands on the child’s knees to improve motion.

- Hip rotation: While the child lies flat with legs extended, a caregiver gently rolls the entire leg inward and outward.

Casting and Bracing

If the hip’s range of motion becomes restricted or X-rays show developing deformities, a cast or brace may be used to keep the femoral head properly aligned within the acetabulum.

- Petrie Casts: These are two long-leg casts connected by a bar, holding the legs in an “A” position. Typically applied in an operating room, the procedure involves:

- Arthrogram: A dye is injected into the hip joint, allowing detailed X-ray images to assess the femoral head’s shape and confirm proper positioning.

- Tenotomy: If the adductor longus muscle in the groin is too tight, a minor procedure called a tenotomy is performed to release the tension and improve hip rotation before casting.

The cast is usually worn for 4 to 6 weeks, after which physical therapy is resumed to restore hip and knee mobility. If necessary, casting may be repeated until the hip enters the final healing stage.

By employing these tailored treatment strategies, the goal is to ensure proper bone regrowth and minimize future complications, allowing children with Perthes disease to lead active and healthy lives.

Petrie casts keep the legs spread far apart in an effort to keep the hips in the best position during healing.

Petrie casts keep the legs spread far apart in an effort to keep the hips in the best position during healing.

Surgical Treatment for Perthes Disease

Surgery may be recommended to ensure proper alignment of the hip bones and maintain the femoral head securely within the acetabulum during the healing process. Surgical intervention is often considered under the following circumstances:

- Age: Children diagnosed at age 8 or older are at greater risk of femoral head deformity during the reossification stage, making precise alignment crucial.

- Severity of Damage: When more than 50% of the femoral head is affected, keeping it within the rounded acetabulum can support optimal bone regrowth and functionality.

- Ineffectiveness of Nonsurgical Treatments: If nonsurgical approaches fail to maintain the hip’s proper position for healing, surgery becomes a more viable option.

Common Surgical Procedure: Osteotomy

The most frequently performed surgery for Perthes disease is an osteotomy, a procedure in which the bone is carefully cut and repositioned to ensure the femoral head fits securely within the acetabulum. This alignment is stabilized using screws and plates, which are typically removed once the healing stage of the disease is complete.

Surgical treatment aims to optimize the hip’s alignment, reduce the risk of long-term complications

In many cases, surgical treatment involves cutting the femur to realign the joint properly. In some instances, the acetabulum (hip socket) may need to be deepened if the femoral head has enlarged during the healing process and no longer fits securely within the socket. After completing either procedure, the child is typically placed in a cast for several weeks to protect the corrected alignment.

Post-Cast Care and Recovery

Once the cast is removed, a structured recovery process begins:

- Physical Therapy: Your child will undergo physical therapy to rebuild muscle strength and restore the hip’s range of motion.

- Mobility Support: Crutches or a walker will be necessary to minimize weight-bearing on the affected hip and reduce stress during the healing phase.

- Ongoing Monitoring: Regular X-rays will be conducted by your child’s doctor to track the progress of hip healing through the final stages of recovery.

This comprehensive approach ensures proper joint alignment, promotes successful healing, and minimizes the risk of long-term complications.

Outcomes of Perthes Disease

In the majority of cases, children with Perthes disease have a favorable long-term prognosis and transition into adulthood without significant hip issues.

However, the potential for future problems increases if deformities persist in the shape of the femoral head. If the deformed femoral head (ball) maintains a proper fit within the acetabulum (socket), complications may be avoided. Conversely, when the femoral head does not fit well into the socket, there is a higher risk of hip pain or the early onset of arthritis in adulthood.

Close monitoring and timely intervention are essential to promote optimal hip development and minimize long-term challenges.