Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is a hip disorder that primarily affects adolescents and pre-adolescents who are still in their growth phase. The condition arises when the ball-like head of the femur (thighbone) slips off the neck of the bone in a backward direction, although the exact cause remains unclear. This misalignment can lead to symptoms such as hip pain, stiffness, and reduced stability. Typically, SCFE progresses gradually over time, making early detection crucial.

The primary treatment for SCFE is surgical intervention to stabilize the femoral head and prevent further slippage. Prompt diagnosis is essential to achieving the best possible outcomes. Delayed treatment can result in severe complications, such as accelerated degeneration of the femoral head or the development of painful arthritis in the hip joint

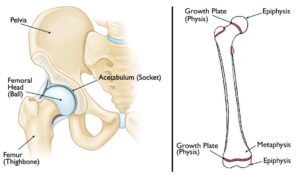

Anatomy

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint, where the socket is formed by the acetabulum, a part of the pelvic bone, and the ball is the femoral head, located at the upper end of the femur. Unlike other bones that grow outward from the center, the femur lengthens through specialized areas of developing cartilage known as growth plates (physes) located at its ends.

Growth plates act as transitional zones between the widened part of the bone shaft (metaphysis) and the end of the bone (epiphysis). At the upper end of the femur, the epiphysis serves as the growth center, eventually forming the femoral head

Description

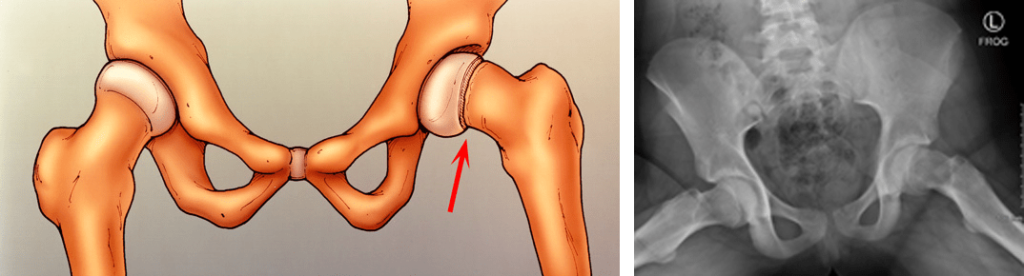

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is the most prevalent hip condition among adolescents. It occurs when the epiphysis, or the femoral head, shifts downward and backward off the femoral neck at the growth plate, a structurally weaker area that has not yet fully matured. SCFE is often associated with periods of rapid growth, typically during puberty. It is most common in boys aged 12 to 16 and girls aged 10 to 14.

In some cases, SCFE can develop suddenly following minor trauma or a fall, but more frequently, it progresses gradually over weeks or months without a clear preceding injury.

SCFE is categorized based on the patient’s ability to bear weight on the affected hip, which helps physicians determine the appropriate course of treatment. The two main types are:

- Stable SCFE: Patients can bear weight on the affected hip, either independently or with crutches. This is the most common form of SCFE.

- Unstable SCFE: Patients cannot bear weight on the affected hip, even with crutches. This type is more severe and requires urgent medical attention. Complications, such as avascular necrosis (loss of blood supply to the femoral head), are more likely with unstable SCFE.

Although SCFE typically affects only one hip, it can occasionally occur on the opposite side. When this happens, it usually develops within 18 months of the initial episode.

Cause

The exact cause of slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) remains unknown. However, it is more likely to occur during periods of rapid growth and is more prevalent in boys than in girls.

Several risk factors increase the likelihood of developing SCFE, including:

- Excessive weight or obesity: The majority of patients with SCFE are above the 95th percentile for weight.

- Family history: A genetic predisposition to SCFE can raise the risk.

- Endocrine or metabolic disorders: Conditions such as hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism are more commonly associated with SCFE in patients who fall outside the typical age range of 10 to 16 years.

Symptoms

The symptoms of SCFE can vary depending on the severity of the condition and whether the slip is classified as stable or unstable.

For stable SCFE, where the femoral head shifts gradually, common symptoms include:

- Intermittent pain in the groin, hip, knee, or thigh, often persisting for weeks or months and worsening with physical activity.

- A noticeable limp after prolonged activity such as walking or running.

- A tendency to position the affected leg in external rotation, leading to an outward-facing (out-toed) gait.

In contrast, unstable SCFE, where the femoral head shifts suddenly, presents more severe symptoms, including:

- A sudden onset of intense pain, often following a minor injury or fall.

- An inability to bear weight on the affected leg.

- External rotation of the affected leg, causing it to turn outward.

- A visible leg-length discrepancy, where the affected leg appears shorter than the unaffected leg.

Early recognition of these symptoms is critical for timely diagnosis and treatment to prevent complications and ensure the best possible outcome.

A 11-year-old boy with unstable SCFE. His affected leg is turned outward and is shorter than the other leg.

A 11-year-old boy with unstable SCFE. His affected leg is turned outward and is shorter than the other leg.

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination

During the evaluation, the doctor will gather detailed information about your child’s overall health, medical history, and current symptoms. They will ask specific questions about when the symptoms started and how they have progressed.

While your child is lying down, the doctor will conduct a thorough examination of the affected hip and leg to identify signs of SCFE. Key observations during the physical examination may include:

- Pain during extreme hip movements, indicating irritation or instability.

- Restricted range of motion, particularly a reduced ability to internally rotate the hip.

- Involuntary muscle guarding and spasms, which occur as a protective response to avoid painful movement.

Additionally, the doctor will assess your child’s gait by observing how they walk. Children with SCFE often exhibit a limp or an abnormal walking pattern that signals hip dysfunction.

This detailed examination is critical for accurately diagnosing SCFE and determining the severity of the condition.

Your doctor will check range of motion in the affected hip, if the SCFE is stable.

Your doctor will check range of motion in the affected hip, if the SCFE is stable.

X-rays

X-rays are a key diagnostic tool for visualizing dense structures like bones. To confirm a diagnosis of SCFE, the doctor will request X-rays of your child’s pelvis, hip, and thigh from at least two different angles.

In cases of SCFE, the X-ray images typically reveal the femoral head slipping off the neck of the femur, a characteristic sign of the condition. These detailed images allow the doctor to assess the severity of the slip and guide appropriate treatment planning.

Open Reduction

For patients with unstable SCFE, a more extensive surgical procedure called open reduction may be required. In this approach, the surgeon makes a larger incision in the hip and carefully manipulates the femoral head back into its correct anatomical position.

After repositioning the femoral head, one or two metal screws are inserted to secure the bone and maintain proper alignment until the growth plate naturally fuses. While this procedure effectively restores hip stability, it is more complex and involves a longer recovery period compared to other treatment methods.

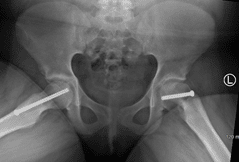

(Left) Preoperative X-ray of an unstable SCFE . (Right) Postoperative X-ray shows that the femoral head has been manipulated back into place and screws have been inserted to hold it in place.

(Left) Preoperative X-ray of an unstable SCFE . (Right) Postoperative X-ray shows that the femoral head has been manipulated back into place and screws have been inserted to hold it in place.

In Situ Fixation in the Opposite Hip

In certain cases, patients with SCFE are at an increased risk of developing the condition in the opposite hip. If your child falls into this higher-risk category, the doctor may recommend preventive treatment by inserting a screw into the unaffected hip during the same surgical procedure.

This proactive approach can significantly reduce the likelihood of SCFE occurring in the opposite hip. The doctor will discuss this option with you in detail and determine whether this additional step is appropriate for your child based on their individual risk factors.

In this X-ray, two screws have been inserted in the patient’s right hip to stop progression of a slip. A single screw has been inserted in the left hip to prevent SCFE from developing.

In this X-ray, two screws have been inserted in the patient’s right hip to stop progression of a slip. A single screw has been inserted in the left hip to prevent SCFE from developing.

Complications

While early diagnosis and appropriate treatment significantly reduce the likelihood of complications from SCFE, some patients may still experience issues. Potential complications include avascular necrosis (AVN), chondrolysis, and hip impingement.

Avascular Necrosis (AVN)

In severe cases of SCFE, the condition can disrupt the blood supply to the femoral head, leading to a gradual and painful collapse of the bone. This condition, known as avascular necrosis (AVN) or osteonecrosis, occurs more frequently in patients with unstable SCFE.

When the bone collapses, the protective articular cartilage covering the femoral head also deteriorates, causing the bones in the hip joint to rub against each other. This bone-on-bone contact results in painful arthritis. In some cases, additional surgeries may be required to reconstruct the hip and alleviate symptoms.

AVN typically develops over time, and its early signs may not appear on X-rays until 12 to 18 months after the initial treatment. Therefore, regular monitoring with X-rays during this period is essential to detect and address AVN promptly.

Chondrolysis

Chondrolysis is a rare but serious complication in which the articular cartilage of the hip joint rapidly deteriorates. This degeneration leads to severe pain, deformity, and a permanent reduction in hip mobility.

Although the exact cause of chondrolysis remains unclear, it is believed to stem from inflammation in the hip joint. Treatment often includes aggressive physical therapy and the use of anti-inflammatory medications to manage symptoms. While some patients may experience a gradual recovery of hip mobility, others may require reconstructive surgery to restore joint function.

Impingement

Hip impingement is another potential complication of SCFE. This can occur due to changes in the shape of the femur or hip socket, or from the placement of the screw used during stabilization surgery. In some cases, this leads to femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), which causes pain and limits the range of motion in the hip.

Treatment for impingement may involve surgical interventions such as screw removal, arthroscopy, or open reconstruction to relieve pain and improve hip function. These procedures are tailored to the individual’s specific needs and severity of the condition.

Illustration and X-ray of in situ fixation. A single screw is inserted to prevent any further slip of the femoral head through the growth plate.

Illustration and X-ray of in situ fixation. A single screw is inserted to prevent any further slip of the femoral head through the growth plate.