introduction

Bone tumours originate from the uncontrolled proliferation of cells within bone tissue, resulting in the formation of an abnormal mass or lump. While the majority of bone tumours are non-cancerous or benign, posing minimal risk to health and typically not spreading to other areas of the body, malignant or cancerous tumours also exist. Malignant bone tumours have the potential to metastasize, spreading cancer cells to distant parts of the body. Treatment approaches for bone tumours vary depending on their nature, ranging from conservative observation for benign tumours to more aggressive interventions such as surgical excision, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy for malignant tumours.

Description:

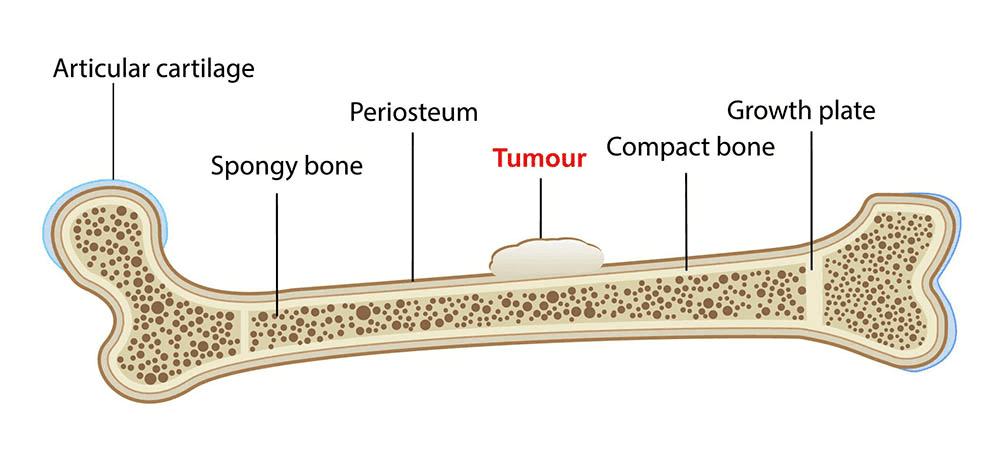

Bone tumours can impact any bone within the body and arise in various regions of the bone, ranging from its surface to the bone marrow at its core. Even benign tumours, as they grow, can damage healthy tissue and compromise bone strength, increasing the risk of fractures.

Cancerous bone tumours can be categorised as either primary or secondary.

Primary bone cancer originates within the bone itself, while secondary bone cancer begins elsewhere in the body before spreading to the bone, a condition known as metastatic bone disease.

Common types of cancers originating elsewhere in the body that frequently metastasize to bone include breast, lung, thyroid, renal (kidney), and prostate cancers.

Primary Bone Cancer: Types and Characteristics

Primary bone cancer encompasses various types, with the four most common being:

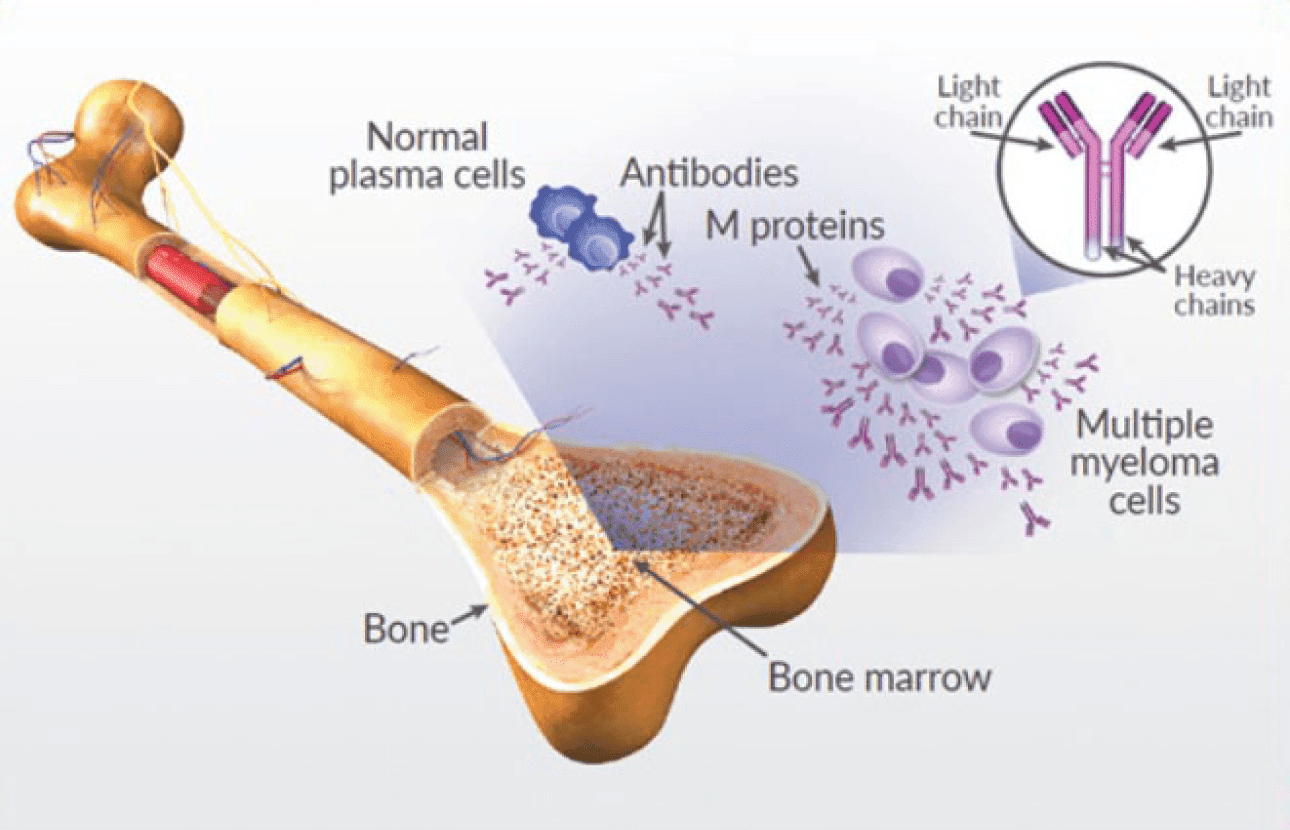

Multiple Myeloma:

This malignancy affects the bone marrow, where it originates as a tumour. It can develop in any bone in the body and is particularly prevalent among individuals aged 50 Treatment typically involves chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and sometimes surgery.

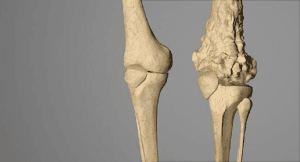

Osteosarcoma:

Ranking as the second most prevalent primary bone cancer, osteosarcoma primarily affects teenagers and children, with the majority of cases occurring around the knee in the femur or tibia. Treatment typically consists of chemotherapy and surgical intervention.

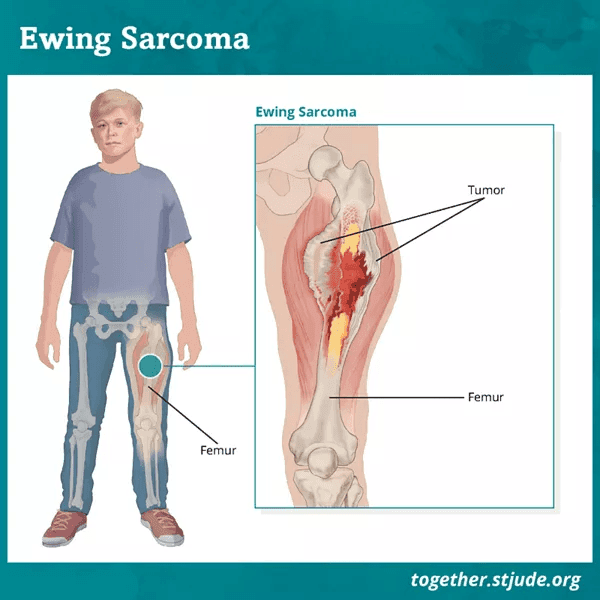

Ewing’s Sarcoma:

Occurring predominantly in individuals aged 5 to 20, Ewing’s sarcoma typically impacts the bones in the upper and lower limbs,pelvis, and ribs. Treatment typically entails a combination of chemotherapy along with either surgical intervention or radiation therapy.

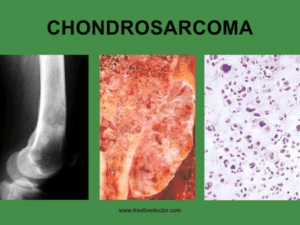

Chondrosarcoma:

This malignant tumour, characterised by cartilage-producing cells, is frequently observed in individuals aged 40 to 70, with most cases localised around the hip, pelvis, or shoulder. Surgery is typically the primary treatment approach for chondrosarcoma.

Benign bone tumours

Benign bone tumours encompass various types, along with certain diseases and conditions that mimic bone tumours, often necessitating similar treatment approaches

Among the common types of benign bone tumours and related conditions are:

- Nonossifying fibroma

- Unicameral (simple) bone cyst

- Osteochondroma

- Giant cell tumour

- Enchondroma

- Fibrous dysplasia

- Chondroblastoma

- Aneurysmal bone cyst

- Osteoid osteoma

These entities require careful evaluation and management, despite their benign nature, to ensure appropriate treatment and optimal outcomes.

Cause

The exact cause of most bone tumours remains unknown.

Symptoms

Individuals with bone tumours often report experiencing localised pain, typically described as dull and aching, in the affected area. Pain may intensify at night and with physical activity.

Additional symptoms of a bone tumour may include fever and night sweats.

In some cases, patients may not exhibit any symptoms but may notice the presence of a painless mass instead.

While bone tumours are not directly attributed to trauma, an injury can occasionally trigger pain in an existing tumour.

Moreover, trauma may result in the fracture of a bone weakened by a tumour, leading to significant discomfort.

On occasion, benign tumours may be discovered incidentally during medical imaging conducted for unrelated reasons, such as evaluating a sprained ankle or knee injury.

Medical Evaluation

Various conditions, including infections and stress fractures, may mimic the symptoms of bone tumours. To diagnose a bone tumour accurately, your physician will perform a comprehensive assessment and prescribe several diagnostic tests.

Medical History Review

During the evaluation, your physician will gather a comprehensive medical history, inquiring about your overall health, current medications, and specific symptoms. They will also explore any familial history of tumours or cancer.

Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination was conducted, focusing on the tumour site. Your doctor will assess for:

- Swelling or tenderness in the affected area

- Changes in the skin covering the tumour

- The presence of a palpable mass

- Impact of the tumour on nearby joints

In some instances, your physician may also examine other regions of your body to exclude cancers that may metastasize to bone.

Diagnostic Tests

X-rays:

These imaging studies offer detailed views of dense structures like bone. X-rays are commonly used to aid in diagnosing bone tumours, as different tumour types may manifest distinct characteristics on these images. Some tumours may erode bone or create lesions, while others prompt excessive bone formation.

Certain tumours may exhibit a combination of these features.

Biopsy:

A biopsy may be required to definitively diagnose a bone tumour. During this procedure, a sample of tissue is extracted from the tumour for examination under a microscope by a pathologist, who specialises in identifying diseases through the study of abnormal cells.

There are two primary methods of conducting a biopsy:

- Needle biopsy: In this approach, a needle is inserted into the tumour to retrieve tissue samples. Before the procedure, a local anaesthetic is administered to decrease discomfort. Typically performed by a radiologist, needle biopsies of bone tumours often utilise imaging techniques such as X-rays, CT scans, or MRI scans to guide the needle accurately.

- Open Biopsy: An open biopsy is conducted in an operating room under general anaesthesia, rendering the patient unconscious throughout the procedure. A surgeon performs the biopsy by making a small incision and extracting tissue samples for examination.

- Additional Tests: In addition to imaging studies and biopsies, your doctor may request blood and urine tests to validate the diagnosis of a bone tumour further or to rule out alternative conditions.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Benign Tumours

If your tumour is benign, your physician may recommend close monitoring to observe any changes. During this period, periodic follow-up X-rays or other tests may be necessary.

Certain benign tumours can be effectively managed with medication, while some may resolve over time without surgery.

Malignant Tumours

A multidisciplinary team of specialists collaborates to deliver comprehensive care for individuals diagnosed with bone cancer. This team may include oncologists specialising in various aspects of cancer treatment, such as orthopaedic oncologists, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, and pathologists.

The primary treatment objective is to eradicate the cancer while preserving function to the greatest extent possible in the affected body area.

Treatment strategies are tailored based on several factors, including the cancer stage. Localised cancer indicates that cancer cells are confined to the tumour and its immediate vicinity. In contrast, metastatic cancer has spread to other parts of the body, presenting a more challenging treatment scenario.

A combination of treatment modalities is often employed for malignant bone tumours:

Radiation Therapy:

High-dose X-rays destroy cancer cells and reduce tumour size. This approach targets cancer within the radiation field without affecting cancer elsewhere in the body. Your physician determines the suitability of radiation therapy based on individual circumstances.

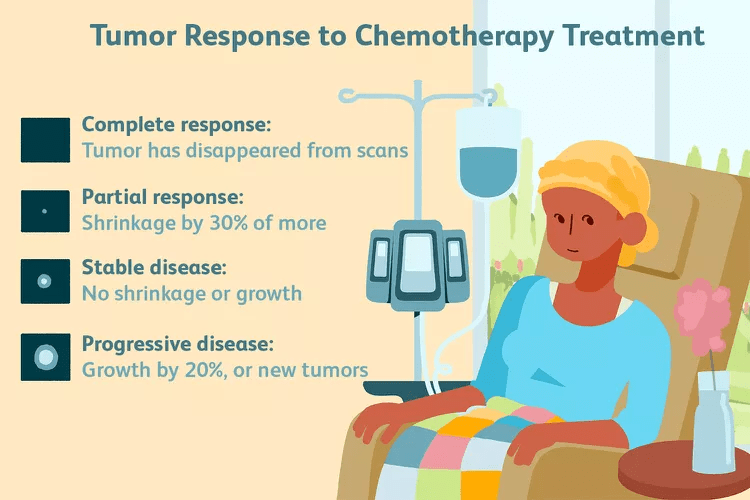

Chemotherapy (Systemic Treatment)

Chemotherapy is administered to eliminate tumour cells that may have entered the bloodstream but are not yet detectable by tests or scans. It is commonly used when cancerous tumours have a high likelihood of spreading. Chemotherapy may be administered intravenously or orally.

Surgical Treatment

Benign Tumours

In certain instances, tumour removal (excision) or alternative surgical methods may be recommended by your physician to mitigate the risk of fractures and disability. Despite appropriate treatment, some tumours may recur intermittently. In rare cases, specific benign tumours have the potential to metastasize or transform into cancerous forms.

Malignant Tumours

Limb Salvage Surgery:

his procedure involves excising the cancerous portion of bone while preserving adjacent muscles, tendons, nerves, and blood vessels whenever feasible.

The surgeon will remove the tumour with a margin of healthy tissue. The void left by the excised bone may be filled with a metallic implant (prosthesis), bone graft from elsewhere in the body, or donated bone.

Amputation:

In cases where the tumour is extensive and involves nerves and blood vessels, amputation—surgical removal of all or part of a limb—may be necessary. Following amputation, a prosthetic limb can assist with functional restoration.

In cases where the tumour is extensive and involves nerves and blood vessels, amputation—surgical removal of all or part of a limb—may be necessary. Following amputation, a prosthetic limb can assist with functional restoration.

Recovery

The duration and complexity of recovery depend on the tumour type and the surgical procedure performed.

Additional X-rays and imaging studies may be ordered after treatment completion to confirm tumour eradication.

Regular follow-up appointments and periodic tests every few months are essential post-treatment.

Despite tumour disappearance, vigilant body monitoring for signs of recurrence is crucial. Early detection of recurrent tumours is imperative, as they can present significant challenges if undetected.