Introduction to Ankle Anatomy

The ankle joint functions like a hinge but is far more complex than a simple hinge joint. It comprises several critical structures that contribute to its unique design, making it an exceptionally stable joint. This stability is essential as the ankle must support 1.5 times your body weight during walking and up to eight times your body weight while running.

Normal ankle function is crucial for a smooth and effortless gait. The muscles, tendons, and ligaments surrounding the ankle work in harmony to propel the body forward. Any condition that disrupts the ankle’s normal function can lead to pain and difficulty in performing daily activities.

This guide aims to explain:

- The key components of the ankle

- How the ankle joint functions

Important Structures of the Ankle

The ankle is made up of several key components, categorized as follows:

- Bones and joints

- Ligaments and tendons

- Muscles

- Nerves

- Blood vessels

The top of the foot is known as the dorsal surface, while the bottom, or sole, is called the plantar surface.

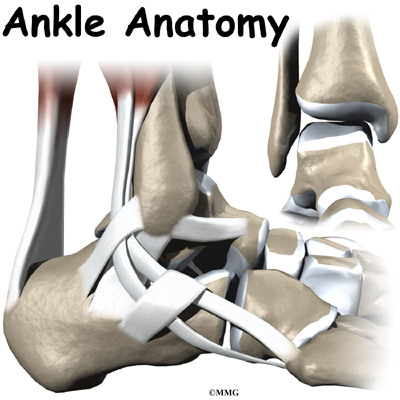

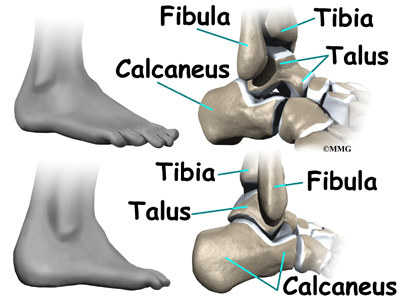

Bones and Joints

The ankle joint is formed by the connection of three main bones:

- Talus: This bone serves as the central part of the ankle joint.

- Tibia: The lower end of the shinbone forms a socket that holds the talus.

- Fibula: The smaller bone of the lower leg helps form this socket.

The talus sits above the calcaneus (heelbone), creating a stable hinge joint. This hinge allows for two primary movements:

- Dorsiflexion: Moving the foot upward.

- Plantarflexion: Moving the foot downward.

The design of the ankle joint resembles the mortise and tenon technique used by woodworkers and craftsmen, a construction method known for its strength and stability in making furniture and buildings.

Inside the ankle joint, the bones are covered with a smooth material called articular cartilage. This cartilage allows the bones to glide against each other effortlessly. In weight-bearing joints such as the ankle, hip, and knee, this cartilage layer is approximately one-quarter of an inch thick. It is both soft enough to absorb shocks and durable enough to last a lifetime—provided it remains free of injury.

Ligaments and Tendons of the Ankle

Ligaments are soft tissues that connect bones to other bones, while tendons attach muscles to bones. Both are composed of collagen fibers, which are bundled together in a rope-like structure. The thickness of a ligament or tendon determines its strength, much like the strands of a rope.

Ligaments in the Ankle Ligaments on either side of the ankle joint play a critical role in stabilizing the bones:

- Lateral Ligament Complex: Located on the outer side of the ankle (farthest from the body’s center), this complex consists of three ligaments:

- Anterior Talofibular Ligament (ATFL)

- Calcaneofibular Ligament (CFL)

- Posterior Talofibular Ligament (PTFL)

- Deltoid Ligament: A thick ligament on the inner side of the ankle (closest to the other ankle), providing medial support.

Additional ligaments stabilize the lower end of the leg where the tibia and fibula meet to form a hinge for the ankle:

- Anterior Inferior Tibiofibular Ligament (AITFL): Connects the tibia and fibula at the front of the ankle.

- Posterior Inferior Tibiofibular Ligament (PITFL) and Transverse Ligament: Provide stability across the back of the tibia and fibula.

- Interosseous Ligament: A long sheet of connective tissue between the tibia and fibula, extending from the knee to the ankle.

The ligaments around the ankle also contribute to the joint capsule, a watertight sac surrounding the joint. This capsule is made of ligaments and soft tissues that fill gaps between them.

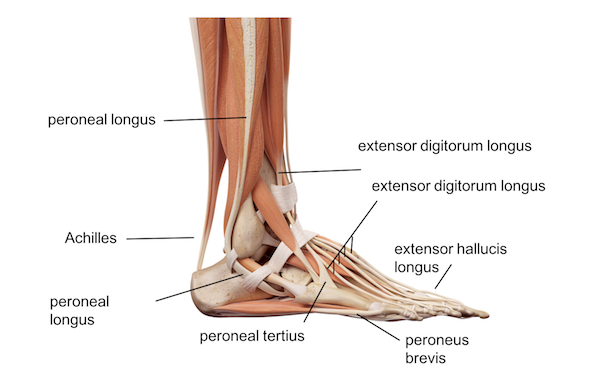

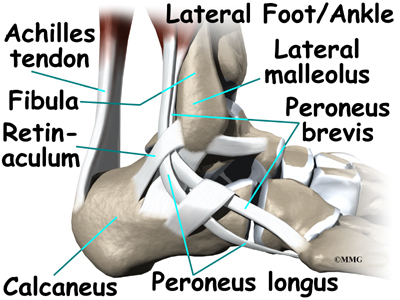

Tendons Supporting the Ankle Tendons near the ankle provide movement and additional stability:

- Achilles Tendon: Attaches the calf muscles to the heelbone (calcaneus), enabling walking, running, and jumping.

- Posterior Tibial Tendon: Connects a smaller calf muscle to the foot’s underside, supporting the arch and helping turn the foot inward.

- Anterior Tibial Tendon: Assists in raising the foot.

- Peroneal Tendons: Two tendons running behind the lateral malleolus (outer ankle bump), aiding in turning the foot downward and outward.

Muscles of the Ankle

The movement of the ankle is primarily driven by the powerful muscles in the lower leg. These muscles connect to the foot via tendons that pass by the ankle. When these muscles contract, they enable the ankle to move, facilitating actions like walking, running, and jumping.

Key muscles involved in ankle movement include:

- Peroneals (Peroneus Longus and Peroneus Brevis): Located along the outer edge of the ankle and foot, these muscles allow the ankle to bend downward and outward.

- Calf Muscles (Gastrocnemius and Soleus): Connected to the calcaneus (heelbone) by the Achilles tendon, these muscles bend the ankle downward when they contract.

- Posterior Tibialis: Supports the arch of the foot and helps turn the foot inward.

- Anterior Tibialis: Pulls the ankle upward during movement.

Nerves of the Ankle

The ankle receives its nerve supply from nerves passing through the area on their way to the foot:

- Tibial Nerve: Travels behind the medial malleolus (inner ankle bump).

- Nerve Crossing the Front of the Ankle: Extends to the top of the foot, controlling muscles and providing sensation.

- Nerve Along the Outer Edge: Supplies the muscles and skin on the outer edge of the ankle and foot.

These nerves not only control movement but also provide sensation to the top and outer edge of the foot.

Blood Vessels of the Ankle

The ankle’s blood supply comes from arteries that pass through the area en route to the foot:

- Dorsalis Pedis Artery: Runs along the front of the ankle to the top of the foot, where its pulse can be felt in the middle of the foot.

- Posterior Tibial Artery: Travels behind the medial malleolus, branching into smaller vessels that supply the inside edge of the ankle.

- Additional smaller arteries from various directions also contribute to the blood supply of the ankle.

Summary

The anatomy of the ankle is a complex system of interconnected structures. When these components—muscles, tendons, ligaments, nerves, and blood vessels—work in harmony, the ankle functions seamlessly. However, damage to any part can disrupt the entire system, leading to pain and functional issues in both the ankle and foot.