Stress fractures are tiny cracks in a bone or significant bruising within the bone, often resulting from overuse or repetitive stress. These injuries are particularly prevalent among runners and athletes engaged in sports that involve frequent running, such as basketball and soccer.

Typically, the pain associated with stress fractures develops gradually and intensifies during weightbearing activities. A common symptom is localized tenderness at the site of the fracture.

Stress fractures may also arise when individuals alter their activity patterns—for instance, by starting a new exercise regimen, abruptly increasing workout intensity, or changing exercise surfaces, such as transitioning from a treadmill to outdoor jogging. Additionally, conditions like osteoporosis or other bone-weakening disorders can make stress fractures more likely, even during routine daily activities.

The bones in the foot and lower leg are especially susceptible to stress fractures due to the repetitive impact they endure during activities like walking, running, and jumping.

To recover effectively, it is crucial to avoid high-impact activities temporarily. Resuming activity too soon can prolong recovery and elevate the risk of a complete fracture, which requires significantly more time to heal and can further delay a return to normal activities.

Description

Stress fractures often develop due to repetitive strain on the bones, resulting in microscopic damage over time. Unlike acute fractures caused by sudden trauma, such as a broken leg from a fall, stress fractures occur gradually when repetitive motions overwhelm the body’s ability to heal between activity sessions. This is a common issue among athletes who engage in high-impact activities.

Bone tissue undergoes a continuous renewal process called remodeling, where old bone is broken down and replaced by new bone. Excessive physical activity can disrupt this balance, leading to a breakdown of bone tissue that outpaces repair, thereby weakening the bone and increasing the risk of stress fractures.

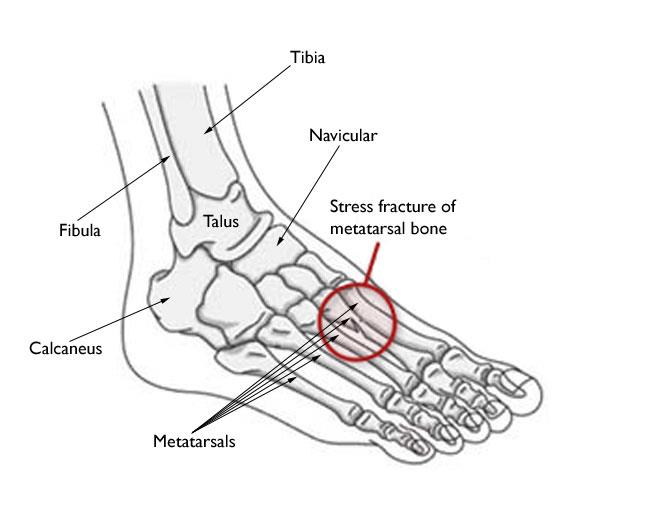

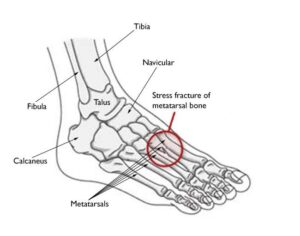

Common Locations of Stress Fractures in the Foot and Ankle

Stress fractures frequently affect the metatarsal bones in the foot and ankle, particularly:

- Second and Third Metatarsals: These thinner, longer bones are more vulnerable due to the significant force exerted on them when pushing off during walking or running. Ballet dancers are particularly susceptible, as are individuals with a disproportionately larger second metatarsal bone. Pain is typically felt in the middle of the foot.

- Fourth and Fifth Metatarsals: Less commonly affected, fractures here can cause pain on the outside of the foot. Due to limited blood flow to specific areas (e.g., the base of the fifth metatarsal), these fractures often take longer to heal.

Stress Fractures of the Fifth Metatarsal Base

Fractures at the base of the fifth metatarsal, commonly known as Jones fractures, were first identified by Sir Robert Jones. These injuries typically present as pain on the outer midfoot without a clear acute injury and are prevalent among high-level athletes.

Healing can be challenging due to the poor blood supply to this region. Non-surgical treatment typically involves immobilization in a cast or boot for at least six weeks, along with supplements like vitamin D or bone stimulators to enhance healing. Athletes may require up to 12 weeks before returning to sports. In some cases, surgery is necessary and may involve screws, bone grafting, or plates. Post-operative adherence to activity restrictions is critical for recovery.

The most common sites for stress fractures in the foot are the metatarsal bones.

The most common sites for stress fractures in the foot are the metatarsal bones.

Stress Fractures of the Calcaneus (Heel Bone)

The calcaneus, or heel bone, is the second most common site for stress fractures. Symptoms include heel pain during exercise, which may resemble plantar fasciitis or heel spurs. Diagnosis often requires an MRI for confirmation.

Stress Fractures of the Navicular

Stress fractures in the navicular bone, located in the midfoot, cause vague pain that worsens with weightbearing and high-impact activities such as sprinting or jumping. Due to the bone’s rarity as a fracture site, diagnosis may require advanced imaging like CT or MRI scans. Treatment typically involves a cast and non-weightbearing activities, with surgery sometimes needed to stabilize the bone.

Stress Fractures of the Talus

Although uncommon, stress fractures of the talus—a bone in the ankle—can cause heel or ankle pain. Diagnosis and treatment often involve imaging and immobilization, with surgical intervention rarely required.

Stress Fractures of the Sesamoids

The sesamoids, two small bones beneath the big toe joint, help facilitate toe movement during walking and running. Stress fractures in these bones cause localized pain at the base of the big toe. Diagnosis may involve advanced imaging like MRI scans due to the difficulty of detecting fractures on X-rays.

Cause

The primary cause of stress fractures is a sudden increase in physical activity, which can take various forms:

- Frequency: Exercising more often, such as adding extra workout days per week.

- Duration or Intensity: Engaging in longer or more strenuous activities, like running longer distances or high-impact exercises, especially after gaining weight.

Stress fractures are not exclusive to athletes. For instance:

- Infrequent walkers may develop a stress fracture after excessive walking during a vacation, especially on uneven surfaces.

- Wearing a new type of shoe that poorly absorbs repetitive forces can increase the risk of stress fractures.

Bone Insufficiency

Bone strength can be compromised by long-term conditions or medications, such as osteoporosis. This can lead to stress fractures during everyday activities. For example, winter months with reduced Vitamin D levels can make bones more susceptible to fractures.

Studies also highlight that female athletes are at a higher risk due to a condition known as the “female athlete triad”. This condition, caused by excessive dieting or exercise, includes three interconnected issues: eating disorders, menstrual irregularities, and early-onset osteoporosis. Reduced bone mass significantly raises the likelihood of stress fractures.

Poor Conditioning

A common trigger for stress fractures is attempting “too much, too soon.” This is often seen in individuals starting new exercise routines or athletes resuming training after a break.

For example, runners who reduce training during the off-season might resume their previous intensity without easing back into the regimen. Ignoring discomfort, overtraining, and insufficient recovery time can overwhelm bones, leading to fractures.

Improper Technique and Equipment

Faulty mechanics in how the foot absorbs impact, such as due to a blister, bunion, or tendinitis, can alter weight distribution and place excessive strain on specific bones, increasing fracture risk.

Additionally, using worn-out or poorly cushioned shoes that lack shock-absorbing properties can further contribute to stress fractures.

Changes in Surface

Switching training or playing surfaces can also elevate the risk. For instance, tennis players moving from grass courts to hard courts, or runners transitioning from treadmills to outdoor tracks, may experience increased stress on their bones.

Symptoms of Stress Fractures

The most common symptom of a stress fracture in the foot or ankle is pain, which typically:

- Develops gradually and worsens during weightbearing activities.

- Subsides with rest but recurs with physical activity.

Other symptoms may include:

- Swelling on the top of the foot or outer ankle.

- Tenderness to the touch at the fracture site.

- Possible bruising.

First Aid

If you suspect a stress fracture, seek medical attention promptly to avoid further complications, such as a complete bone break. Until your appointment, follow the RICE protocol:

- Rest: Avoid activities that put weight on the injured foot. If necessary, wear supportive footwear like thick-soled sandals.

- Ice: Apply cold packs for 20 minutes several times daily to reduce swelling. Avoid direct contact with the skin.

- Compression: Lightly wrap the area with a soft bandage to control swelling.

- Elevation: Keep the foot raised above heart level as often as possible.

Over-the-counter NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen can help alleviate pain and swelling.

Doctor Examination

Your doctor will review your medical history, including lifestyle, activities, diet, and medications, to identify potential risk factors. If you’ve had stress fractures previously, additional tests may be conducted to check for deficiencies, such as low calcium or Vitamin D levels.

During the physical exam, the doctor will assess for tenderness and gently press on the affected area. Pain localized to the fracture site is often a key diagnostic indicator.

Imaging Tests

To confirm the diagnosis, doctors may order imaging tests such as:

- X-rays: While initial X-rays may not detect stress fractures due to their small size, healing bone (callus) often becomes visible after a few weeks, revealing the fracture site.

(Left) This X-ray of a patient who reported pain in the second metatarsal does not show an obvious stress fracture. (Right) Three weeks later, an X-ray of the same patient shows callus formation at the site of the stress fracture.

(Left) This X-ray of a patient who reported pain in the second metatarsal does not show an obvious stress fracture. (Right) Three weeks later, an X-ray of the same patient shows callus formation at the site of the stress fracture.