Flatfoot, medically referred to as progressive collapsing foot deformity (PCFD) and previously known as adult-acquired flatfoot (AAF), is a complex condition affecting the foot and ankle. This disorder leads to the flattening of the foot’s arch and may also involve less apparent deformities. Another term often used for this condition is posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD).

Flatfoot is commonly associated with issues in the posterior tibial tendon, a vital structure responsible for maintaining the arch’s stability and support. When this tendon becomes inflamed or sustains damage, it can compromise its ability to stabilize the arch, ultimately resulting in the development of flatfoot.

Description

Progressive collapsing foot deformity encompasses a wide spectrum of conditions that can begin as mild, subtle deformities with minimal symptoms. However, without proper intervention, it may progress to a severely painful and debilitating flatfoot condition that significantly impairs mobility and function.

In the early stages, most patients can manage the condition effectively with non-surgical treatments, such as orthotics and supportive braces.

For cases where orthotics and braces fail to alleviate symptoms, surgical intervention may be necessary to relieve pain and restore foot function. The type of surgery depends on the severity of the condition and the extent of the deformity. Some procedures involve straightforward solutions, like removing inflamed tissue or repairing minor tendon tears. However, more advanced cases often require complex surgical techniques, and patients may still experience some limitations in activity post-surgery.

Anatomy

The normal arch of the foot is supported by several key anatomical structures, including tendons (which connect muscles to bones) and ligaments (which connect bones to one another). Two of the most critical components for maintaining a healthy foot arch are:

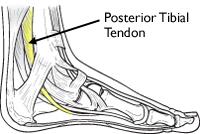

The Posterior Tibial Tendon (PTT): This tendon links the tibialis posterior muscle in the calf to the bones along the inner arch of the foot. It runs behind the inside bump of the ankle, known as the medial malleolus, and plays a crucial role in maintaining the arch. The PTT also supports the foot during walking and aids in movements like standing on the toes or turning the foot and ankle inward.

The Spring Ligament: This ligament connects the calcaneus (heel bone) to the navicular bone on the inside of the foot. It is essential for maintaining the structural integrity of the foot’s arch and supporting its function during movement.

The posterior tibial tendon attaches the calf muscle to the bones on the inside of the foot.

Whether inflammation and impaired function of tendons and ligaments are a cause or a result of flatfoot remains a subject of debate. However, dysfunction of the posterior tibial tendon (PTT) is widely regarded as a primary factor contributing to the development of progressive collapsing foot deformity (PCFD).

In some cases, the spring ligament sustains damage before the PTT begins to deteriorate. Even if this ligament is intact initially, it often becomes torn or stretched during the later stages of flatfoot progression.

Other supporting structures, such as smaller ligaments that connect the inner foot bones, also play a role in maintaining the arch. Among these, the deltoid ligament, a strong structure connecting the ankle to the heel and inner foot bones, is particularly important. As flatfoot worsens, the deltoid ligament becomes overstretched and weakened, contributing to deformities that may extend to the ankle.

Causes of PCFD

PCFD can result from various factors, which may differ from patient to patient. Common causes include:

Midfoot arthritis or ligament laxity: These conditions place added stress on the PTT, potentially leading to gradual tearing.

Acute injuries: Traumas such as falls can inflame or tear the PTT.

Overuse: Repetitive strain from high-impact sports like basketball, tennis, or soccer can cause PTT tears. Even non-athletes can develop similar issues over time, especially when wearing non-supportive footwear like sandals.

Genetics: There appears to be a significant hereditary component to PCFD development.

The Vicious Cycle of Flatfoot Progression

Regardless of the initial cause, flatfoot progression often follows a predictable pattern:

The PTT becomes inflamed and weak, reducing its ability to support the arch and stabilize the foot during movement.

The arch begins to sag, placing additional stress on other supporting structures, such as the spring ligament.

These structures also stretch and weaken, forcing the PTT to compensate further, which accelerates its deterioration.

Over time, the tendon and ligaments may tear completely, leading to significant bone misalignment. This misalignment can cause pain from bone impingement and arthritis.

Risk Factors

Flatfoot and PTT dysfunction are more prevalent in women and individuals over the age of 40. Additional risk factors include obesity, diabetes, and hypertension.

Symptoms of PCFD

Pain along the arch or inner side of the foot and ankle: This is where the PTT is located. Swelling may accompany inflammation or tearing. Pain may precede visible deformity.

Pain and weakness during activity: Activities like walking, standing for long periods, or participating in high-impact sports can become challenging. Pain is often worse when wearing non-supportive footwear. Weakness may also make it difficult to push off or stand on your toes.

Pain on the outer ankle: As the arch collapses, the heel bone may shift outward relative to the ankle. In severe cases, this can cause impingement, where the heel bone presses against the outer ankle bone, leading to additional pain.

The most common location of pain is along the course of the posterior tibial tendon (yellow line), which travels along the back and inside of the foot and ankle.

The most common location of pain is along the course of the posterior tibial tendon (yellow line), which travels along the back and inside of the foot and ankle.

Doctor’s Examination of Flatfoot

Medical History and Physical Examination

To diagnose progressive collapsing foot deformity (PCFD), your doctor will begin by reviewing your medical history and discussing your symptoms.

During the physical examination of the foot and ankle, the doctor will look for key signs of the condition, including:

Swelling and pain along the posterior tibial tendon: Tenderness and swelling are typically located just behind and below the inner ankle bone. The arch of the foot may also be sensitive or painful.

Visible changes in foot shape: The doctor will assess the foot while you are standing. A flat arch is often the earliest and most noticeable deformity. As the condition advances, other deformities may develop, such as the heel shifting outward from beneath the ankle and the toes angling outward in relation to the foot and ankle.

These deformities are best observed by examining the heel from behind the patient. In a healthy foot, the heel aligns straight under the calf, and only the fourth and fifth toes are visible. In contrast, a flatfoot deformity may cause the heel to angle outward, revealing more toes from this view—a hallmark sign referred to as the “too many toes” sign.

This patient has posterior tibial tendon dysfunction with a flatfoot deformity. (Left) The front of her foot points outward. (Right) The “too many toes” sign. Even the big toe can be seen from the back of this patient’s foot.

Difficulty with the Single-Limb Heel Rise Test

The single-limb heel rise test is a simple yet important evaluation of the posterior tibial tendon’s function. Successfully standing on one leg and rising onto the toes requires a healthy and well-functioning posterior tibial tendon.

If a patient is unable to perform this test—either by failing to maintain balance on one leg or being unable to lift the heel off the ground—it may indicate a problem with the posterior tibial tendon. This inability is a common sign of tendon dysfunction associated with conditions like progressive collapsing foot deformity (PCFD).

This patient is able to perform a single limb heel rise on the right leg.

Limited Flexibility and Range of Motion

Limited flexibility is another key factor in diagnosing posterior tibial tendon dysfunction and flatfoot. During the examination, your doctor may assess the foot’s ability to move side to side. This flexibility is crucial for determining the appropriate treatment plan. A rigid or immobile foot often requires different interventions compared to a flexible foot.

Flatfoot can also affect the ankle’s range of motion, particularly in upward movement (dorsiflexion). This limitation is often caused by tightness in the calf muscles, which restricts the natural movement of the ankle joint.

Imaging Tests

To confirm the diagnosis and assess the severity of the condition, your doctor may recommend imaging tests, including:

X-rays: X-rays provide detailed images of bones and are essential for detecting issues like arthritis or changes in bone alignment that contribute to pain and deformities. For flatfoot, weightbearing X-rays (taken while standing) are particularly helpful, as they reveal deformities more accurately than non-weightbearing images. If surgery is being considered, X-rays also assist in measuring deformities and planning the most appropriate surgical approach.

(Top) An X-ray of a normal foot. Note that a line through the center of the ankle bone (talus) and a line through the rest of the foot are parallel, indicating a normal arch. (Bottom) In this X-ray the lines diverge, which is consistent with flatfoot deformity.

(Top) An X-ray of a normal foot. Note that a line through the center of the ankle bone (talus) and a line through the rest of the foot are parallel, indicating a normal arch. (Bottom) In this X-ray the lines diverge, which is consistent with flatfoot deformity.

Advanced Imaging Tests for Flatfoot Diagnosis

In some cases, advanced imaging tests are necessary to provide a more detailed understanding of the condition and guide treatment planning. These tests offer insights into both the bones and soft tissues involved in flatfoot deformity.

Computerized Tomography (CT) Scan:

CT scans produce 3D images of the bones, offering a more comprehensive view than traditional X-rays. Surgeons often use CT scans to detect subtle changes or abnormalities in bone alignment that may not be visible on standard X-rays. This helps identify which deformities or arthritic joints need surgical correction.

Ideally, CT scans should be performed while the patient is standing (weightbearing CT) to evaluate how the bones align under load. However, weightbearing CT requires specialized equipment that may not be available at all facilities.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI):

MRI scans are particularly valuable for assessing soft tissues, such as tendons and ligaments, which X-rays and CT scans cannot visualize as effectively. Doctors may order an MRI to check for inflammation, tears, or other issues in the posterior tibial tendon or related structures. MRI can also help rule out other potential causes of symptoms when the diagnosis is uncertain.

Ultrasound:

Ultrasound imaging uses high-frequency sound waves to create real-time images of the body’s internal structures. While it can be used to evaluate the posterior tibial tendon, ultrasound is generally not the primary diagnostic tool for flatfoot and is only ordered in specific cases.

Nonsurgical Treatment for Flatfoot

Most patients experience relief from flatfoot symptoms with nonsurgical treatments. However, recovery can be prolonged. Pain may persist for over three months, even with early intervention. For those who have experienced pain for an extended period, it’s not unusual for discomfort to continue for up to six months after starting treatment.

Rest

Reducing or stopping activities that exacerbate pain is the first step. Switching to low-impact exercises like biking, swimming, or using elliptical machines can be beneficial, as these activities place less stress on the foot. Additionally, weight loss can significantly reduce the strain on the arch and its supporting structures.

Ice Therapy

Applying a cold pack to the most painful area of the posterior tibial tendon for 20 minutes, three to four times daily, helps reduce swelling. Always place a barrier between the ice and skin to prevent injury. Using ice immediately after exercise can minimize inflammation around the tendon.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Medications like ibuprofen or naproxen can help alleviate pain and inflammation. NSAIDs are available over the counter, or your doctor may prescribe stronger versions like meloxicam. Topical anti-inflammatory gels can also provide localized relief. However, these medications address symptoms but do not treat the underlying condition or correct foot deformities. Discuss potential side effects, especially if you have heart, kidney, or stomach concerns, with your doctor before use.

Orthotics

Shoe inserts designed to support and align the foot are a common nonsurgical treatment for flatfoot.

Over-the-counter orthotics are suitable for mild deformities and are widely available.

Custom orthotics are recommended for moderate to severe changes in foot structure. Though more expensive, they offer tailored support.

Braces

Simple lace-up ankle braces may help mild to moderate flatfoot by supporting the ankle and relieving tendon strain.

Advanced braces, such as the Arizona or Richie braces, are often used for severe cases involving stiffness or arthritis. These braces are customized and can sometimes delay the need for surgery.

Immobilization

For severe cases, a short leg cast or walking boot may be worn for 6–8 weeks to allow the tendon to rest and reduce swelling. Immobilization is generally followed by a brace to support the foot after initial symptoms improve.

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy can strengthen the posterior tibial tendon and improve flexibility in the calf and Achilles tendon. Stretching these muscles helps alleviate tightness and enhances ankle motion, which is critical for flatfoot management.

Steroid Injections

Cortisone injections are powerful anti-inflammatory treatments. While commonly used for arthritis, injections into the posterior tibial tendon are rare due to the risk of tendon rupture. Always discuss potential risks with your doctor before considering this option.

Surgical Treatment for Flatfoot

Surgery is considered when pain persists despite several months of nonsurgical treatment. The type of surgery depends on factors such as the severity of the deformity, the presence of arthritis, and the foot’s flexibility. Flatfoot reconstruction can be complex, often requiring a combination of procedures to address various aspects of the deformity.

Tenosynovectomy (Cleaning the Posterior Tibial Tendon)

This procedure is for mild cases where pain and swelling are present, but foot shape remains largely unchanged. The surgeon removes inflamed tissue (synovium) around the tendon and may repair small tears. While effective, the tendon may continue to degenerate over time.

Gastrocnemius Recession or Achilles Tendon Lengthening

These procedures lengthen the calf muscle or Achilles tendon to improve ankle flexibility and prevent recurrence of flatfoot. Performed through a small incision, these surgeries are often combined with other corrective techniques. Complications, though rare, include nerve damage and muscle weakness.

Tendon Transfer

Tendon transfer procedures replace or supplement the damaged posterior tibial tendon using another tendon, such as the flexor digitorum longus (FDL) or flexor hallucis longus (FHL). While the foot remains functional, additional surgeries may be needed to correct the foot’s shape and reduce future stress on the tendons.

Ligament Repair

Surgeons often repair the spring ligament and other arch-supporting ligaments if they are torn or stretched. Repairs may involve using natural ligament tissue or supportive materials like strong stitches. As with tendon transfers, ligament repair is typically part of a larger surgical plan to reshape the foot.

Osteotomy (Cutting and Shifting Bones)

Osteotomies involve cutting and repositioning bones to restore a more natural arch shape, reducing strain on the posterior tibial tendon and supporting ligaments.

Common procedures include moving the heel bone (calcaneus) to its proper position and lengthening the outer portion of the heel to correct the “too many toes” deformity.

Bone grafts and fixation devices like screws or plates may be used to ensure proper healing.

X-ray of a foot as viewed from the side in a patient with a more severe deformity. This patient required fusion of the middle of the foot in addition to a tendon transfer and cut in the heel bone.

X-ray of a foot as viewed from the side in a patient with a more severe deformity. This patient required fusion of the middle of the foot in addition to a tendon transfer and cut in the heel bone.

Arthrodesis (Joint Fusion)

In some cases, flatfoot is accompanied by stiffness or arthritis in critical foot joints, making traditional treatments like bone cuts and tendon transfers ineffective. Joint fusion (arthrodesis) is a surgical option to realign the foot and alleviate arthritis-related pain.

- What Does Arthrodesis Involve?

The procedure involves removing cartilage from the affected joint and securing the bones in a corrected alignment using screws or plates. Over time, the bones fuse to form a single, solid structure, eliminating the joint and associated arthritis pain. - Application in Flatfoot Surgery:

- In rigid flatfoot, the heel bone may need to be repositioned and fused beneath the ankle bone.

- To restore the arch, bones along the inner side of the foot may also require fusion.

- Benefits and Motion Impact:

While fusion eliminates movement in the fused joints, patients with rigid deformities typically have little to no motion in these joints before surgery. This procedure can improve walking mechanics and reduce pain, particularly on the outer ankle, by addressing arthritis and impingement between the heel and ankle. Importantly, the ankle’s up-and-down motion is generally unaffected. - Risks:

A potential complication of arthrodesis is nonunion, where the bones fail to fuse together. If this occurs, a second surgery may be required.

Ankle Surgery for Advanced Flatfoot

In severe cases, flatfoot deformity may progress to the ankle joint, leading to instability or arthritis. Depending on the condition, different surgical interventions may be recommended:

- Ligament Repair:

If the ankle joint is unstable but not arthritic, the surgeon may repair the deltoid ligament, which stabilizes the inside of the ankle. - Ankle Replacement or Fusion:

For arthritic or stiff ankles, more extensive procedures like ankle replacement or fusion may be necessary to correct the deformity and relieve pain. These operations aim to restore function and improve the quality of life for patients with advanced flatfoot.

This X-ray shows a very stiff flatfoot deformity. A fusion of the three joints in the back of the foot is required and can successfully recreate the arch and allow restoration of function.

This X-ray shows a very stiff flatfoot deformity. A fusion of the three joints in the back of the foot is required and can successfully recreate the arch and allow restoration of function.