The hip is a ball-and-socket joint, where the rounded top of the femur (thighbone) fits securely within a curved socket in the pelvis known as the acetabulum. In adolescents with hip dysplasia, however, the joint has not formed as it should—the acetabulum is too shallow to fully support and cover the femoral head. This structural irregularity can lead to hip pain and may accelerate the onset of osteoarthritis, a degenerative joint condition where the protective cartilage wears down, causing bone-on-bone contact.

Adolescent hip dysplasia often originates from developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), a condition present at birth or in early childhood. Although newborns are regularly screened for DDH, some cases remain unnoticed or are mild enough to go untreated. As a result, symptoms of hip dysplasia may not manifest until adolescence.

The primary goal in treating adolescent hip dysplasia is to alleviate pain and maintain the natural hip joint for as long as possible. Often, this involves surgical intervention to correct the joint’s anatomy, potentially delaying or preventing the progression of painful osteoarthritis.

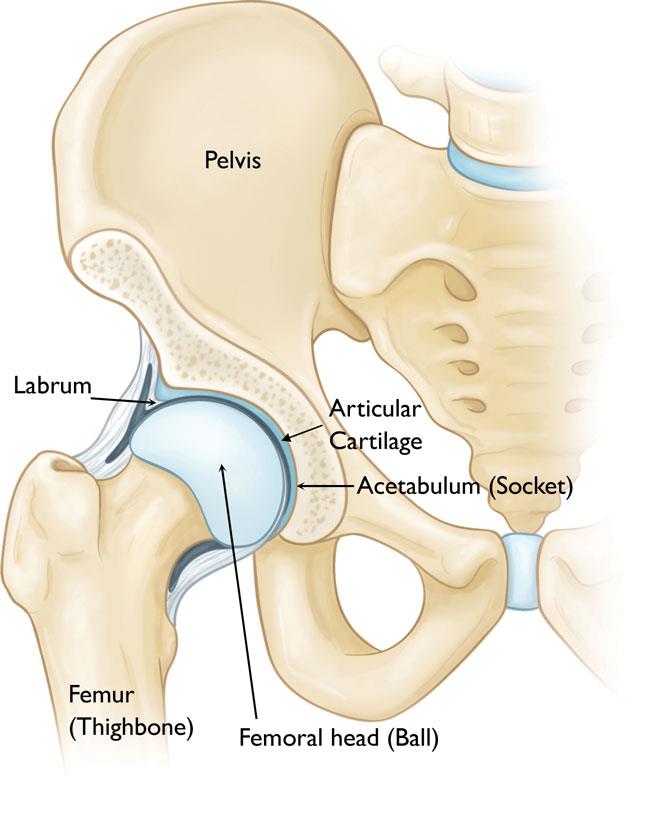

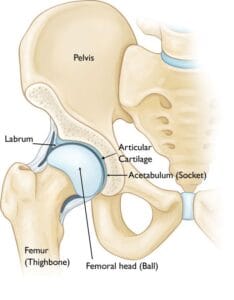

Anatomy

The hip is among the largest joints in the human body, functioning as a ball-and-socket structure. The “socket” component, known as the acetabulum, is part of the large pelvic bone. The “ball” is formed by the femoral head, which is the upper portion of the femur (thighbone). Both the femoral head and the acetabulum are coated with articular cartilage—a smooth, slippery tissue that cushions the bones, allowing them to move fluidly and reducing friction.

Surrounding the acetabulum is a ring of durable fibrocartilage called the labrum. This labrum acts like a gasket, creating a snug seal around the socket and stabilizing the femoral head within the joint.

Description

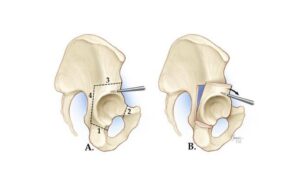

In individuals with hip dysplasia, the acetabulum is underdeveloped, making it too shallow for the femoral head to fit securely within the socket.

This anatomical irregularity disrupts the typical distribution of forces across the joint, causing the labrum to absorb more stress than usual. Consequently, excessive force concentrates on a smaller area of the hip cartilage and labrum. Over time, this can lead to the gradual wearing away of the articular cartilage, while the labrum may become torn or damaged. Such degenerative changes heighten the risk of developing early-onset osteoarthritis.

The extent of hip dysplasia can vary significantly:

- In mild cases, the femoral head may simply have some looseness within the socket.

- In more severe instances, the joint may exhibit complete instability, or the femoral head may be fully dislocated from the socket.

Cause

Adolescent hip dysplasia often stems from developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), a condition that may go unnoticed or untreated during infancy or early childhood.

DDH can run in families, passed down from one generation to the next. It can affect either hip but typically involves the left hip. While it can develop in anyone, certain factors increase the likelihood:

- Female gender

- Firstborn status

- Breech birth position (bottom-first instead of head-first)

Symptoms

Hip dysplasia in young children generally does not cause pain. However, as time passes, altered forces within the hip joint lead to degenerative changes—gradual damage to the articular cartilage and labrum—which can become painful.

Commonly, the pain associated with hip dysplasia:

- Centers in the groin area, though it may occasionally radiate to the outside of the hip

- Starts as mild and intermittent but can become more frequent and intense over time

- Worsens with activity or toward the end of the day

Some individuals may also experience sensations of locking, catching, or popping in the groin.

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination

During a physical exam, the doctor will review your child’s medical history and discuss symptoms. They will move the hip in various directions to evaluate the range of motion and attempt to replicate any pain or discomfort.

Imaging Tests

In many cases, a physical examination is sufficient to diagnose adolescent hip dysplasia. However, doctors may recommend imaging tests to exclude other potential causes of pain and to confirm the diagnosis.

- X-rays: X-rays provide images of bones and help the doctor assess the alignment between the acetabulum and femoral head. They can also reveal signs of arthritis.

- Computerized Tomography (CT) Scans: More detailed than standard X-rays, CT scans offer a clearer view of the severity of dysplasia.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Scans: MRIs create detailed images of soft tissues, which can help the doctor detect damage to the labrum and articular cartilage.