A talus fracture involves a break in one of the critical bones that form the ankle joint. These fractures are typically associated with high-impact injuries, such as those resulting from car accidents or falls from significant heights.

Given the talus bone’s crucial role in facilitating ankle movement, fractures in this area can lead to a significant reduction in mobility and overall joint function. Improper healing of a talus fracture can result in serious complications, including chronic pain, arthritis, and difficulty walking. Due to these risks, surgical intervention is often necessary to ensure proper alignment and healing of the bone.

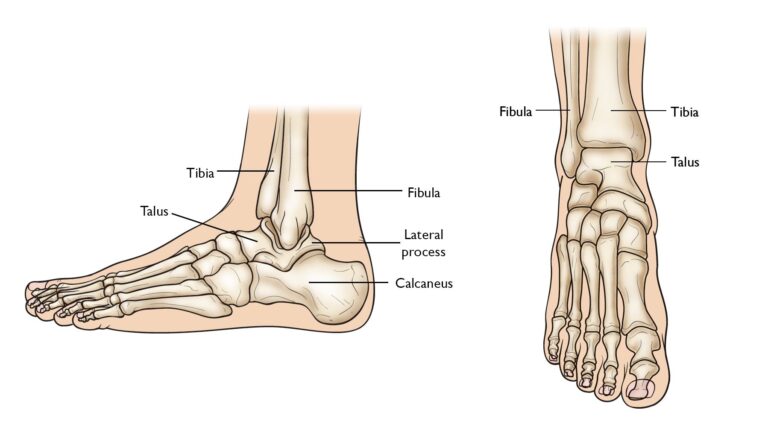

Anatomy

The talus bone forms the lower segment of the ankle joint, while the tibia and fibula comprise the upper part. This joint is essential for enabling up-and-down movement of the foot. Positioned above the heel bone, or calcaneus, the talus works with it to form the subtalar joint. This joint facilitates inward and outward foot movement, a critical function for maintaining balance while walking on uneven surfaces.

The talus serves as a vital connection between the foot and leg, transferring weight and pressure across the ankle joint. Most of its surface is covered with articular cartilage, a smooth, slippery tissue that reduces friction and allows seamless motion between the talus and neighboring bones.

The talus bone sits between the bones of the lower leg and the calcaneus (heel bone).

The talus bone sits between the bones of the lower leg and the calcaneus (heel bone).

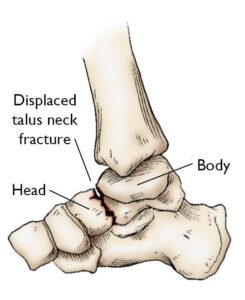

Description of Talus Fractures

Fractures of the talus can affect any part of the bone, but they most commonly occur in the midsection, known as the “neck.” This region lies between the “body” of the talus, located under the tibia, and the “head” of the talus, which extends further into the foot. Another type of talus fracture involves the lateral process, a prominent structure on the outer side of the bone. These fractures often result from the ankle being forced outward and are frequently observed in snowboarders.

Classification of Talus Fractures

- Minimally Displaced or Stable Fractures:

In minimally displaced fractures, the bone fragments remain aligned or are only slightly out of position. These fractures typically heal without the need for surgery, as the bones stay stable throughout the recovery process. - Displaced Fractures:

A displaced fracture occurs when bone fragments shift significantly from their normal positions. The severity of displacement often correlates with the force of the injury. Highly displaced fractures are usually unstable and require surgical intervention to restore proper alignment, offering the best chance for the ankle and foot to regain full function. - Open Fractures:

An open fracture, also known as a compound fracture, occurs when the broken bone pierces through the skin. This type of injury often damages surrounding muscles, tendons, and ligaments. Open fractures are exposed to external debris, increasing the risk of infection. Consequently, they require meticulous treatment and tend to have longer recovery periods.

The talus often breaks in the mid-portion — or “neck” — of the bone. This illustration shows a displaced talus neck fracture.

The talus often breaks in the mid-portion — or “neck” — of the bone. This illustration shows a displaced talus neck fracture.

Causes

The majority of talus fractures result from high-impact trauma, such as car accidents or falls from significant heights. Although less common, sports injuries—particularly in activities like snowboarding—can also lead to talus fractures due to the stress placed on the ankle during sudden movements or impacts.

Symptoms of a Talus Fracture

Individuals with a fractured talus often experience the following symptoms:

- Severe, acute pain

- Inability to walk or bear weight on the affected foot

- Noticeable swelling, bruising, and tenderness in the ankle and foot area

Medical Examination for Talus Fractures

Due to the intensity of symptoms, most patients with talus fractures seek immediate treatment at urgent care centers or emergency rooms.

Physical Examination

During the evaluation, your doctor will review your medical history and symptoms, followed by a detailed physical examination. The exam will include:

- Inspecting the foot and ankle for visible cuts or lacerations caused by the injury.

- Testing the ability to move toes and checking sensation in the sole of the foot, as nerve injuries may accompany the fracture.

- Assessing the pulse at key points of the foot to ensure adequate blood flow to the toes and foot.

- Evaluating for signs of compartment syndrome, a dangerous condition where fluid buildup in the muscles can lead to loss of function and sensation. If diagnosed, this requires emergency surgical treatment.

- Examining other potential injuries, such as fractures in the legs, pelvis, or spine, to provide a comprehensive assessment.

Imaging Tests for Talus Fractures

Diagnostic imaging plays a crucial role in confirming the fracture and planning treatment.

- X-rays: X-rays are the most commonly used imaging technique to assess fractures. They can reveal whether the talus is broken, if bone fragments are displaced, and how many pieces the bone has been fractured into. This information helps the doctor decide whether surgical intervention is necessary.

An X-ray of a talus neck fracture.

An X-ray of a talus neck fracture.

First Aid for Talus Fractures

Immediate care for a talus fracture involves immobilizing the injured foot and ankle to prevent further damage. A well-padded splint, extending from the toes to the upper calf, is typically applied to stabilize and protect the limb. Elevating the foot above heart level helps reduce swelling and alleviate pain. Since treatment depends on the type and severity of the fracture, seeking prompt medical attention is essential.

Nonsurgical Treatment

While most talus fractures require surgery due to the high-energy nature of the injury, certain stable and well-aligned fractures can be managed without surgical intervention. These cases often involve a combination of immobilization and rehabilitation.

- Casting:

A cast is used to hold the fractured bones in place during the healing process. The cast is typically worn for 6 to 8 weeks, and patients are instructed to avoid placing weight on the affected foot. The goal is to allow sufficient healing so that the bone remains stable when weight-bearing resumes. - Rehabilitation:

After the cast is removed, your doctor will provide exercises designed to restore the range of motion and strengthen the foot and ankle. Rehabilitation is a critical phase in achieving full recovery.

Surgical Treatment

When the bone fragments have shifted out of their normal position (displaced fractures), surgery is often the best approach to realign and stabilize the bones, minimizing the risk of long-term complications.

- Open Reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF):

In this surgical procedure, the displaced bone fragments are carefully repositioned (a process known as “reduction”) to their natural alignment. The fragments are then secured using special screws or metal plates with screws to ensure stability during healing. ORIF significantly improves the chances of restoring normal foot and ankle function.

(Left) This X-ray shows a talus fracture. (Right) The bone fragments are fixed in place with screws.

(Left) This X-ray shows a talus fracture. (Right) The bone fragments are fixed in place with screws.

Bone Healing and Recovery Timeline

Bones have a remarkable ability to heal, but the severity of your talus fracture significantly impacts the length of your recovery. After surgery, your foot will typically remain in a splint or cast for 2 to 8 weeks, depending on the extent of the injury and the progression of healing. Regular X-rays are taken during follow-up visits to ensure proper bone alignment and healing.

Pain Management After Surgery

Post-surgery pain is a normal part of the healing process. Effective pain management helps speed recovery and improve overall comfort.

- Medications:

Your doctor may prescribe a combination of medications to manage pain, including opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and local anesthetics. This approach minimizes opioid use, as opioids can be addictive if not taken as directed. If pain persists beyond a few days, inform your doctor for further evaluation.

Early Motion and Physical Therapy

Initiating movement of the foot and ankle early in recovery is often encouraged, depending on your level of pain and wound healing.

- After Surgery: Once the surgical wound heals, patients are typically instructed to begin light motion exercises.

- After Nonsurgical Treatment: Patients treated with immobilization can start working on regaining range of motion after the cast is removed.

Specific physical therapy exercises improve flexibility, range of motion, and strengthen the surrounding muscles, aiding in long-term recovery.

Weightbearing Progression

Walking with partial weightbearing begins after clearance from your surgeon, typically two to three months post-injury. During this time, you may need crutches, a cane, or a specialized walking boot. Placing weight on the foot too soon can risk displacing the bone fragments. Always follow your surgeon’s guidelines to avoid complications. As your recovery advances and pain decreases, you can gradually increase the weight placed on your foot.

Complications After Talus Fractures

- Avascular Necrosis (AVN):

Severe fractures can disrupt the blood supply to the talus, potentially leading to avascular necrosis (AVN) or osteonecrosis. In AVN, the bone cells die due to insufficient blood flow, causing the bone to collapse painfully over time. This can also damage the articular cartilage, leading to arthritis, loss of motion, and reduced function. While AVN is more likely in complex fractures, even appropriately treated fractures, including those surgically repaired, carry this risk. - Posttraumatic Arthritis:

Posttraumatic arthritis often develops after a talus fracture, even if the bone heals correctly. Damage to the cartilage during the injury can result in stiffness, pain, and joint degeneration over time. Severe cases of arthritis or AVN may require additional surgical interventions, such as joint fusion or ankle replacement, to alleviate symptoms and restore mobility.