Pilon fractures are a distinct type of injury affecting the lower end of the tibia (shinbone), specifically involving the weight-bearing surface of the ankle joint. These fractures often extend to the fibula, the other bone in the lower leg. Typically resulting from high-impact incidents such as motor vehicle accidents or falls from significant heights, pilon fractures are considered severe and can have lasting effects on ankle function.

The term “pilon” originates from the French word for “pestle,” symbolizing the crushing or splitting nature of the bone often seen in these injuries. Due to the high-energy trauma, the tibia may fracture into multiple fragments or be extensively crushed.

In most cases, surgical intervention is required to realign the bone and restore its structure. Because the force required to cause a pilon fracture is substantial, patients often sustain additional injuries that may also necessitate medical attention

Anatomy of the Ankle Joint

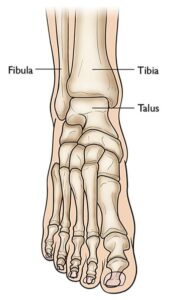

The lower leg consists of two primary bones:

- Tibia: Commonly referred to as the shinbone, it is the larger and more prominent bone of the lower leg.

- Fibula: A slender, smaller bone that runs parallel to the tibia.

At the ankle joint, these bones connect with the talus, a small yet critical bone in the foot that functions as a hinge. Together, the tibia, fibula, and talus form the structure of the ankle joint, enabling stability and movement.

This structure is integral to the ankle’s ability to support weight and provide mobility, emphasizing its importance in overall lower limb function.

The three bones that come together to form the ankle joint.

The three bones that come together to form the ankle joint.

Understanding the Severity of Pilon Fractures

Pilon fractures can vary significantly in their complexity. The tibia may sustain a single break or be shattered into multiple fragments.

The severity of a pilon fracture is influenced by several key factors:

- Number of Fractures: The extent to which the bone is fractured.

- Bone Fragmentation: The size and quantity of the broken pieces.

- Displacement: The alignment of the fractured pieces. In less severe cases, the bone fragments may remain closely aligned. In more complex fractures, significant gaps or overlapping of the fragments may occur.

- Soft Tissue Damage: Injuries to nearby muscles, tendons, and skin often accompany the fracture.

When a fracture causes bone fragments to pierce the skin or creates an open wound that exposes the bone, it is classified as an “open” or compound fracture. This type of fracture is particularly dangerous due to the increased risk of infection in the bone and surrounding tissue. Immediate medical intervention is critical to minimize the likelihood of infection and ensure proper healing.

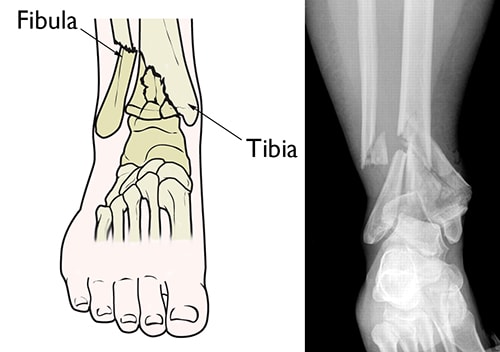

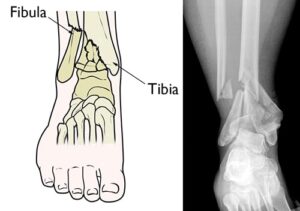

(Left) A pilon fracture often affects both bones of the lower leg. (Right) In this x-ray, both the tibia and fibula are fractured and the pieces of bone are severely displaced.

(Left) A pilon fracture often affects both bones of the lower leg. (Right) In this x-ray, both the tibia and fibula are fractured and the pieces of bone are severely displaced.

Causes of Pilon Fractures

Pilon fractures are most commonly caused by high-energy trauma. Typical scenarios include motor vehicle or motorcycle accidents, falls from significant heights, or skiing incidents.

The increased prevalence of pilon fractures correlates with the widespread use of airbags in modern vehicles. While airbags significantly improve survival rates in high-speed collisions, they do not provide protection to the legs, leaving survivors susceptible to severe lower limb injuries, including pilon fractures.

Symptoms of Pilon Fractures

Pilon fractures are characterized by immediate and intense pain. Additional symptoms may include:

- Swelling

- Bruising

- Tenderness in the affected area

- Difficulty or inability to bear weight on the injured leg

- Visible deformity, where the ankle may appear misaligned or crooked

Doctor Examination and Initial Stabilization

Pilon fractures typically necessitate emergency care due to the severe symptoms and the potential for associated injuries. Patients often present to urgent care or emergency departments following high-energy trauma.

In many cases, these individuals may also sustain additional injuries to other areas such as the head, chest, abdomen, or limbs. Significant blood loss from such injuries can result in shock, a potentially fatal condition that can lead to organ failure.

Physical Examination

During the evaluation, your doctor will:

- Inspect the lower leg and ankle for visible injuries, such as cuts or wounds, and gently apply pressure to identify tender spots.

- Assess toe movement and sensation throughout the foot to rule out nerve damage.

- Check pulses at critical points in the foot to ensure proper blood flow.

- Evaluate the degree of swelling in the foot and ankle, which will help determine the timing of any surgical intervention.

- Conduct a thorough examination of the rest of the body to identify any additional injuries. It is crucial to inform your doctor about any other areas of pain or discomfort.

Imaging Tests for Diagnosis

Imaging studies play a vital role in diagnosing pilon fractures and planning treatment, particularly if surgery is required.

- X-rays: These provide detailed images of the bones and are used to identify fractures or joint misalignments in the leg, ankle, and foot.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scans: CT scans offer more precise information about the fracture’s complexity, showing detailed fracture lines and aiding in surgical planning. A CT scan may be performed immediately or after the application of an external fixator, depending on the treatment timeline.

To fully evaluate your fracture, your doctor may recommend an x-ray (left), a CT scan (center), or a three-dimensional CT scan (right).

To fully evaluate your fracture, your doctor may recommend an x-ray (left), a CT scan (center), or a three-dimensional CT scan (right).