Scoliosis is a spinal condition characterized by an abnormal sideways curvature. Neuromuscular scoliosis (NMS) specifically affects children with underlying medical conditions that compromise muscle control around the spine. Disorders commonly linked to NMS include muscular dystrophy, cerebral palsy, and spina bifida, all of which impact the body’s ability to stabilize and support the spine effectively.

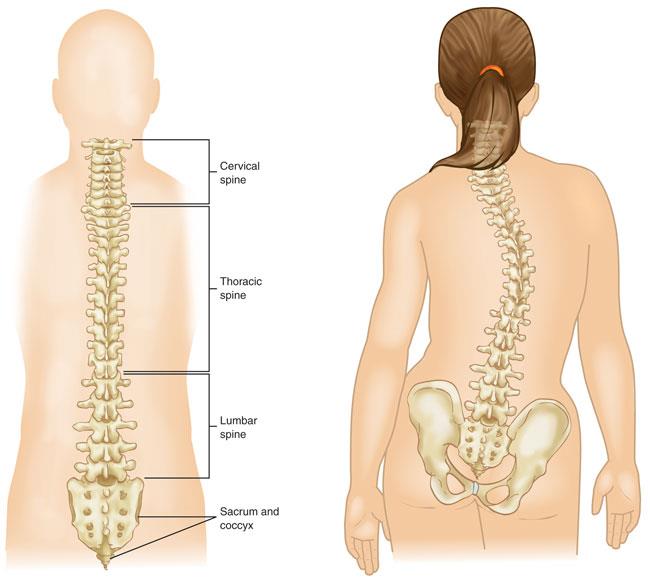

Anatomy

In scoliosis, the vertebrae in the spine tilt or rotate, causing the normally straight spinal column to curve into a shape resembling the letter “C” or “S” instead of aligning vertically down the back.

Children with neuromuscular scoliosis (NMS) often face a range of health challenges alongside spinal curvature. As a result, treatment typically involves a collaborative approach, with specialists from multiple medical fields working together to provide comprehensive care. For many children with NMS, surgical intervention is necessary to correct the curvature and reinforce spinal stability.

Description

Neuromuscular scoliosis (NMS) is one type of scoliosis that can impact children and teens. The other primary types include:

- Idiopathic scoliosis: The most common form, often emerging as children enter puberty. “Idiopathic” indicates that the exact cause of this condition remains unknown.

- Congenital scoliosis: This type arises before birth, where babies may have spinal bones that are incompletely formed or fused together.

Across all scoliosis types, spinal curves tend to become more pronounced during rapid growth phases, such as adolescence. While idiopathic and congenital scoliosis generally affect limited areas of the spine and often stabilize once growth is complete, NMS curves frequently begin at an earlier age. These curves tend to be extensive, involving the entire spine, progressing quickly, and may continue worsening into adulthood.

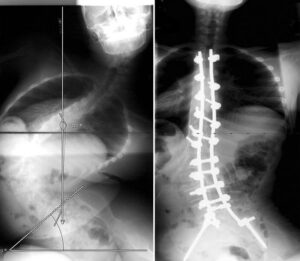

(Left) This adolescent girl with cerebral palsy uses a wheelchair and has a large sweeping curve to the left. (Right) Her X-ray shows a pelvic tilt, which may cause sitting imbalance and lead to pressure sores.

Imaging Tests

Imaging tests are essential for evaluating the extent of your child’s neuromuscular scoliosis (NMS).

- X-rays: X-rays produce clear images of dense structures like bones. They enable the doctor to locate the spinal curve and accurately measure its degree of curvature.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans: MRI scans offer detailed images of soft tissues, helping doctors assess the condition of the spinal cord.

Treatment

Treating neuromuscular scoliosis requires a multidisciplinary approach, often involving specialists in orthopaedics, pediatrics, pulmonology, neurology, urology, nutrition, and gastroenterology. Coordinated care is crucial to ensuring comprehensive treatment. The treatment team is frequently led by the child’s developmental pediatrician.

Treatment approaches vary based on the child’s age, underlying health conditions, and the type and severity of the spinal curvature.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Although nonsurgical treatments do not stop curve progression, they can slow it down, improve function, and enhance quality of life. Common nonsurgical interventions include:

- Wheelchair modification: For children whose pelvic tilt affects balance, wheelchairs can be modified to improve posture. This often includes custom-molded seat backs and adjustments to side positioners for better sitting balance.

- Bracing: For some wheelchair-dependent children, a molded plastic brace around the torso may provide a more stable sitting position and improve arm and hand use. However, unlike in idiopathic scoliosis, bracing cannot halt curve progression in NMS and is not a definitive treatment.For children who can walk, braces might increase the risk of falls due to factors like muscle weakness, respiratory issues, or unsteady gait.

- Physical therapy: Tailored exercises can address muscle imbalances and support physical function.

Surgical Treatment

Indications for Surgery

The treatment team will consider multiple factors to determine if surgery is needed to manage the spinal curve, such as curve severity and its impact on function. Surgery is often recommended when:

- The curve exceeds 50 degrees in a growing child

- The curve exceeds 50 degrees and has progressed over 10 degrees in a fully-grown child

- Sitting becomes difficult, function declines, or there is chronic pain

- There are heart or lung function issues

For non-communicative patients, the decision to proceed with surgery is complex and involves weighing the curve’s size, its effect on sitting balance, and overall care requirements. Input from family or caregivers is crucial in this decision.

Since NMS results from underlying neuromuscular conditions, the treatment plan is often customized. For instance, in patients with hydrosyringomyelia (fluid within the spinal cord), surgical decompression (removing bone pressing on the spinal cord) may stop curve progression, potentially avoiding the need for spinal stabilization.

Surgical Stabilization of the Spine

The primary objectives of spinal stabilization surgery include:

- Stopping curve progression

- Aligning the spine and pelvis to improve sitting tolerance for wheelchair users or walking ability for ambulatory patients

- Enhancing lung function

- Reducing pain

Growing Rods

Standard spine-stabilizing surgeries typically stop growth in the treated section. For young children, temporary stabilization using growing rods is sometimes recommended to allow continued spinal, chest, and lung growth. Growing rods help manage the curve while supporting daily activities.

In this procedure, one or two rods are attached to the spine above and below the curve. Every 6 to 8 months, a minor procedure extends the rods in line with the child’s growth. Once growth is complete, the rods are replaced, and spinal fusion is performed.

A newer option involves magnetically-powered rods (MAGEC), which can be lengthened in a doctor’s office, eliminating the need for repeated surgeries. However, some children with NMS may not be suitable candidates for MAGEC rods due to other magnetic or electronic implants.

Growing rods can stabilize the spine and also allow for continued spine and chest wall growth. (Left) This side-view of the spine shows how the rods are fixed into the upper and lower vertebrae with screws. (Right) This illustration shows how the growing rods are placed in the spine during the surgery. Also shown are the surgical instruments used to hold back the skin and soft tissues to allow the surgeon to access the spine.

Spinal Fusion

Spinal fusion is the most widely used surgical treatment for neuromuscular scoliosis (NMS).

In this procedure, the curved vertebrae are fused together to form a single, solid bone mass, halting growth in the affected spinal segment and preventing future curve progression.

To promote a successful fusion, small pieces of bone graft are placed between the vertebrae. These grafts are sourced from either a bone bank or created from synthetic materials. Over time, the grafted bone integrates with the existing bone, much like the natural healing process of a fractured bone.

Metal rods are usually employed to stabilize the spine until fusion occurs. These rods are secured to the spine with hooks, screws, or wires. Once the grafted bone fully fuses with the surrounding bone, the straightened segment of the spine becomes immobile, preventing further curve progression.

For younger patients who are still growing, spinal fusion may require both anterior (front) and posterior (back) approaches. This two-sided method helps prevent crankshaft syndrome—a condition where growth in unfused areas causes the spine to continue rotating while the fused areas remain fixed.

In children who use wheelchairs and often have a pelvic tilt, the fusion is frequently extended from the upper thoracic spine down to the sacrum (the spine’s base) and pelvis to provide greater stability.

(Left) This patient with cerebral palsy has a large spinal curve to the left. (Right) The spine has been stabilized by two rods and multiple screws, bringing the curve to a more normal alignment.

Complications

Due to the association of neuromuscular scoliosis (NMS) with underlying neuromuscular conditions and the involvement of multiple spinal regions in surgery, the risk of complications following NMS surgery is generally higher than with other types of scoliosis surgeries. Your child’s doctor will discuss possible complications and the preventive measures taken before surgery to reduce these risks.

For example, the treatment team will focus on optimizing your child’s nutritional status, heart health, and lung function to lower the chances of infection and minimize the need for prolonged ventilator support after surgery. Additionally, a thorough skin assessment of the spine and pelvic area will be performed before surgery to further decrease infection risks.