Total knee and hip replacements are among the most commonly performed elective surgeries, significantly improving the quality of life for many patients by relieving pain and enabling them to engage in more active lifestyles.

However, as with any surgical procedure, there are risks involved. Although rare, approximately 1 in 100 patients (or about 1%) who undergo knee or hip replacement surgery may experience an infection following the procedure.

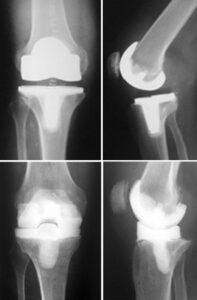

Infections related to joint replacements can either affect the surgical wound or develop deep within the area surrounding the artificial implants, which are made of metal and plastic. These infections can arise during the hospital stay or after the patient returns home, and in some cases, they may even occur years later.

This article will explore:

- The reasons why joint replacements may become infected

- The signs and symptoms of infection

- Effective treatment options for infections

- Preventative measures to reduce the risk of infections

Description:

Infections can potentially spread to your joint replacement from other areas of the body.

Bacterial infections are the primary cause of joint replacement infections. While bacteria naturally reside in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and on our skin, they are typically kept under control by the body’s immune system. For instance, if bacteria enter the bloodstream, the immune system responds quickly to neutralize and eliminate the invading organisms.

However, joint replacements, which are made of metal and plastic, present a unique challenge for the immune system. Metal surfaces attract bacteria, and since these implants do not receive blood flow, the immune system has difficulty detecting and responding to bacterial presence around them. As a result, bacteria may colonize the metal implants, multiply, and lead to an infection in the joint.

Even with the use of antibiotics and preventive measures, patients with infected joint replacements often require surgical intervention to effectively treat the infection.