Understanding Aneurysmal Bone Cysts: Benign Bone Tumours Explained

Aneurysmal bone cysts (ABCs) are non-cancerous lesions that affect bone, often called benign bone tumours.

Although ABCs are not malignant, they can inflict substantial damage to bone tissue, leading to pain or pathological fractures (bone breaks resulting from disease rather than trauma).

They are more prevalent in children than adults and typically manifest within the first two decades of life.

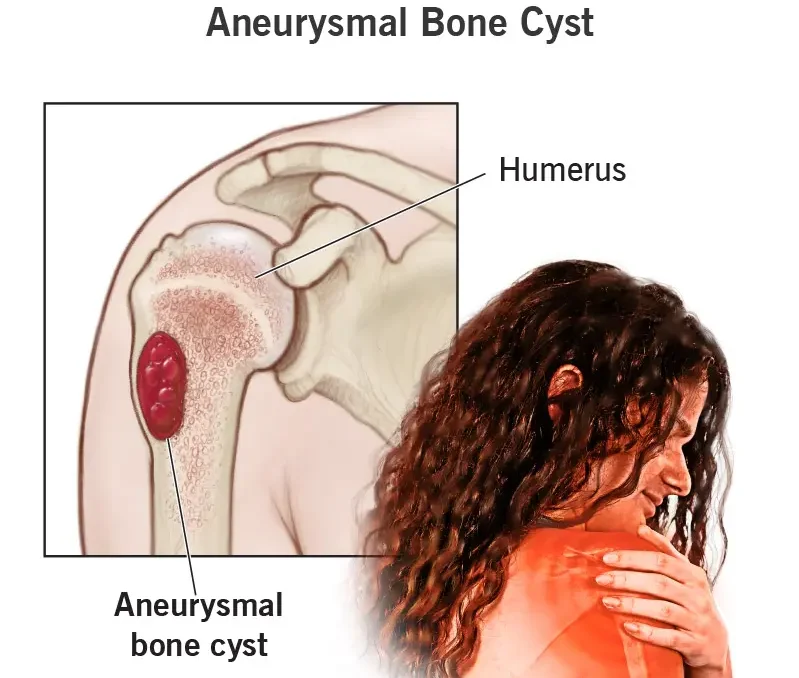

ABCs can develop in any bone throughout the body but are commonly observed in regions surrounding the knee, shoulder, pelvis, and spine. They are typically detected via X-ray imaging.

ABCs may be incidentally discovered following an injury or become apparent due to localised pain and swelling.

Occasionally, the cyst is identified when the bone fractures due to its thinning and weakening effects.

Some ABCs exhibit more aggressive behaviour, resulting in significant bone destruction.

ABCs, Rare Bone Tumours: Key Insights

Aneurysmal bone cysts (ABCs) are uncommon skeletal tumours, affecting less than 1 in 100,000 individuals annually and representing 1 to 2% of primary bone tumours.

Children are more commonly affected by ABCs than adults, with a slightly higher occurrence in females.

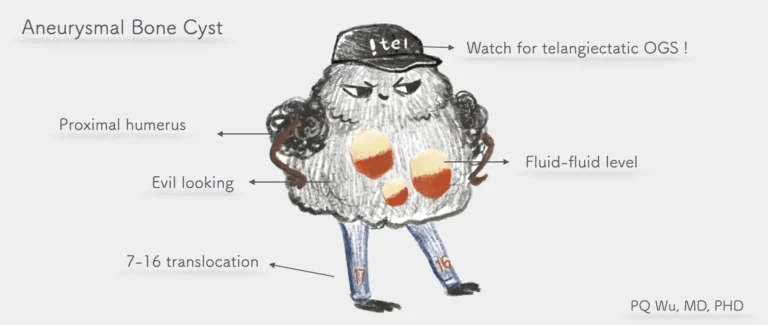

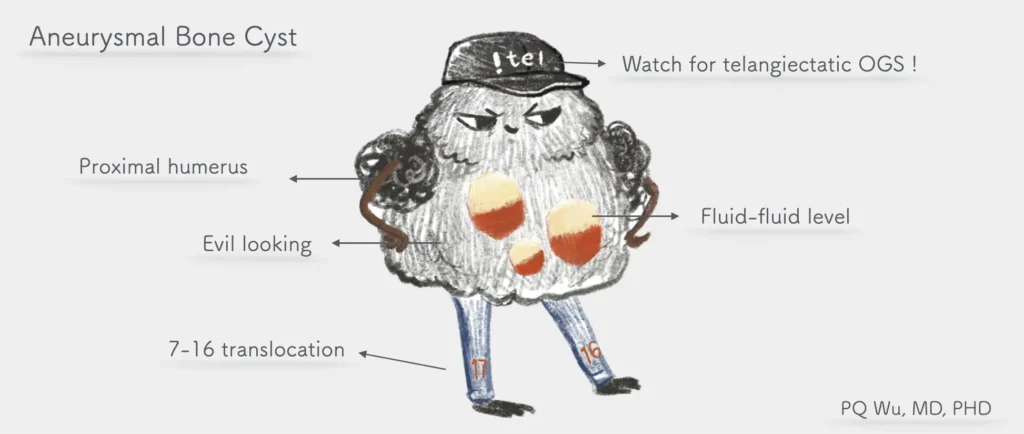

Typically hollow, ABCs comprise varying-sized sacs, or cysts, filled with blood and body fluid. These cysts line the interior and can alter the shape and integrity of normal bone, increasing susceptibility to fractures.

A minority of ABCs present as solid masses.

ABCs most often form near growth plates, the regions at the ends of long bones that facilitate growth in children and adolescents.

A radiograph of a child’s humerus (arm bone) reveals an aneurysmal bone cyst characterised by bone expansion and a markedly thin outer cortex. Confirming the diagnosis typically requires an MRI scan

Cause:

Doctors still do not know the exact cause of aneurysmal bone cysts. However, they are believed to develop during bone growth, often near the growth plates.

Occasionally, an ABC can emerge in response to another benign bone tumour, like chondroblastoma, non-ossifying fibroma, or giant cell tumour. These are referred to as secondary aneurysmal bone cysts, and diagnosing them can be more complex.

Symptoms:

Patients may experience pain and swelling in a bone or joint, often beginning without any apparent injury. These symptoms can worsen gradually over time.

Stiffness could also reduce the range of motion in the affected limb, hand, or foot.

In some cases, a fracture may be the initial sign of an ABC, accompanied by a popping sensation or snapping sound. Pain before the fracture isn’t always present, leading to the discovery of the cyst when seeking treatment for the fracture.

For spinal ABCs, symptoms may include:

- Back or neck pain.

- Nerve pain spreading into the extremities.

- Difficulties with bowel or bladder function.

Occasionally, an ABC may be asymptomatic, detected incidentally during a routine medical examination or X-ray for another condition.

Clinical examination :

The doctor will discuss general health and medical history, inquire about symptoms, and conduct a physical examination. They’ll assess the affected area for swelling, stiffness, deformities, reduced range of motion, pain, or palpable masses.

Imaging:

X-rays

are typically ordered to evaluate the underlying bone. They commonly reveal a bone lesion altering the bone’s shape and strength, often appearing enlarged with a clear central space and thin cortex.

MRI scans may be ordered following X-ray review, with CT scans reserved for rare cases.

A 4-year-old girl complains of pain and swelling in her left upper calf area. An anteroposterior (AP) radiograph reveals a lobular lytic lesion in the proximal tibial meta-diaphysis (indicated by arrows) with a solid periosteal response (indicated by an arrowhead). Sagittal T2-weighted fast spin-echo (FSE) and axial SPAIR MR images (c) depict a solid lesion in the proximal tibia (indicated by arrows) accompanied by soft tissue oedema (indicated by arrowheads). Initially misdiagnosed as TOS by Reader 1, the lesion was later histologically confirmed as an ABC.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

scans play a crucial role in helping doctors identify the boundaries of the tumour, aiding in treatment planning.

Although CT scans

provide superior visualisation of the bone, MRI scans excel in assessing the tissue and fluid within the cyst. A typical MRI depiction of an ABC reveals fluid-fluid levels, indicating the presence of blood and cyst fluid layered within the bone tumour.

Additional Tests

Laboratory Investigations: Most blood tests are not conclusive in diagnosing ABC.

Biopsy Procedure: Confirmation of an ABC diagnosis requires a biopsy. This procedure involves obtaining a tissue sample for microscopic examination by a pathologist. There are two methods for conducting a biopsy:

- Core Needle Biopsy: A small needle is inserted through the skin to extract a bone sample, which is then analyzed under a microscope.

- Open Biopsy: If a larger sample is necessary, the biopsy is performed in an operating room. The surgeon makes an incision to obtain the bone sample.

Genetic Analysis: Genetic testing can be conducted to identify the presence of the USP6 gene, which has been associated with many cases of aneurysmal bone cysts. Pathologists may include this analysis as part of the biopsy procedure to aid in diagnosis.

Navigating the Maze of Treatment Options for Aneurysmal Bone Cysts

Treatment options for bone and soft tissue tumours vary, and it’s essential to consult with your or your child’s doctor to tailor the treatment plan for the best outcome.

Surgery remains the primary treatment approach for ABCs, with the majority of patients undergoing tumour removal. Various surgical techniques are available:

Curettage and bone grafting involve scraping the tumour from the bone, aiming to remove as much of the tumour as possible while preserving healthy bone and the growth plate.

Additional measures, such as using a burr, laser, hydrogen peroxide, liquid nitrogen, or phenol, may be employed to target microscopic tumour cells.

Following tumour removal, the surgeon fills the bone void with a bone graft or substitute.

Bone grafts may be sourced from the patient (autograft) or a donor (allograft).

Allografts contain only the mineral structure of bone, devoid of living cells, eliminating the need for special matching or anti-rejection medication.

Alternatively, bone graft substitutes, typically composed of calcium phosphate or calcium sulphate with other minerals, facilitate new bone growth.

In some cases, bone support with plates, screws, or other hardware may be necessary.

Post-surgery, patients may require splints, casts, slings, or braces to aid in recovery.

Wide Resection

The surgical technique of wide resection, or en bloc resection, involves excising a significant portion of bone containing the cyst. Typically, this approach is reserved for severe bone damage or recurrent cysts.

Wide resection often necessitates bone reconstruction using donor bone (allograft) or artificial implants, such as metal bone replacements.

Sclerotherapy or Radiotherapy (Radiation Therapy)

Sclerotherapy and radiotherapy serve as alternative options for treating large, challenging-to-access tumours that may pose risks during surgery.

These treatments are mainly considered for ABCs located in critical areas like the spine or pelvis, where surgical intervention could endanger vital nerves.

Sclerotherapy

This minimally invasive procedure injects a solution directly into the tumour or surrounding blood vessels to induce its closure. Multiple sessions may be required for complete tumour elimination.

Radiotherapy

Utilising targeted radiation, radiotherapy aims to eradicate tumour cells and prevent a recurrence.

Recovery and Surveillance

Following treatment, the objective is to eliminate the cyst, alleviate pain, and promote average bone growth. Recovery duration varies based on the cyst’s size and location, typically spanning 3 to 6 months for bone healing.

However, recurrence remains a concern, occurring in approximately 25% of cases. Therefore, regular follow-ups are crucial to monitor healing progress and detect any signs of recurrence.

Surveillance involves periodic X-ray assessments every 3 to 6 months, often continuing for up to 2 years or until skeletal maturity is reached.