This article focuses on traumatic hip dislocation, a severe condition resulting from high-impact injuries. For information about developmental hip dislocation in children, refer to Developmental Dislocation (Dysplasia) of the Hip (DDH). For details about dislocation following total hip replacement, consult Total Hip Replacement.

Traumatic hip dislocation happens when the femoral head (the top of the thighbone) is forcibly ejected from its socket in the pelvic bone. This condition typically results from significant trauma, such as high-speed car accidents or falls from considerable heights. Due to the intensity of the force required, hip dislocations often occur alongside other injuries, such as fractures.

Prompt medical intervention is critical, as a hip dislocation is a serious emergency requiring immediate attention.

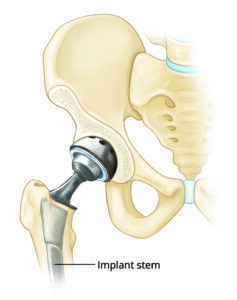

Anatomy of the Hip Joint

The hip is a classic ball-and-socket joint designed for stability and mobility.

- The Socket (Acetabulum): Part of the pelvis, the acetabulum forms the “socket” that houses the femoral head.

- The Ball (Femoral Head): The upper end of the femur serves as the “ball,” fitting snugly into the acetabulum.

Both the ball and socket are covered by articular cartilage, a smooth tissue that minimizes friction, allowing seamless movement. Surrounding the acetabulum is a ring of strong fibrocartilage called the labrum, which acts as a gasket. The labrum helps seal the joint, contributing to its stability. Additionally, ligaments—thick bands of connective tissue—reinforce the joint and further enhance stability.

In a healthy hip, the head of the femur stays firmly within the acetabulum.

What Happens During a Hip Dislocation?

A hip dislocation occurs when the femoral head is forced out of its socket. Depending on the direction of the dislocation, it can be classified as either posterior or anterior:

- Posterior Dislocation: This is the most common type, accounting for roughly 90% of cases. The femoral head is pushed backward out of the acetabulum. Patients with this type of dislocation often present with the lower leg fixed in a position where the knee and foot are rotated inward toward the center of the body.

- Anterior Dislocation: Less common, this occurs when the femoral head is pushed forward out of the socket. The hip will be only slightly bent, with the knee and foot rotated outward, away from the body’s center.

When the hip dislocates, it frequently causes damage to surrounding soft tissues, such as the ligaments, labrum, and muscles that support the joint. The nerves near the hip may also suffer injury, adding to the complexity of the condition.

This comprehensive understanding of hip anatomy and dislocation mechanisms underscores the importance of timely diagnosis and treatment to preserve joint functionality and prevent long-term complications.

Causes

The most frequent cause of traumatic hip dislocations is motor vehicle collisions. These dislocations often occur when the knee strikes the dashboard, driving the thigh backward and forcing the femoral head out of the hip socket. Wearing a seatbelt significantly lowers the risk of hip dislocation during such accidents.

Other potential causes include:

- Falls from significant heights (e.g., from a ladder) or industrial accidents, which can exert enough force to dislocate the hip.

- Sports injuries from high-impact activities like football or hockey, though these are less common.

Hip dislocations are often accompanied by additional injuries, such as fractures of the pelvis or legs and trauma to the back, abdomen, knees, or head. One of the most common associated injuries is a posterior wall acetabular fracture-dislocation, where the femoral head breaks off part of the hip socket during the injury.

Symptoms

A hip dislocation causes severe pain and renders the affected leg immobile. If nerves around the hip are damaged, the patient may experience numbness in the foot or ankle.

Diagnosis

A hip dislocation is a medical emergency, requiring immediate attention. Do not attempt to move the injured individual; instead, keep them warm and call for emergency assistance.

If the dislocation is the sole injury, an orthopaedic specialist can often diagnose it by observing the leg’s abnormal position. However, since hip dislocations are often accompanied by other injuries, a comprehensive physical examination is essential.

Diagnostic imaging tests include:

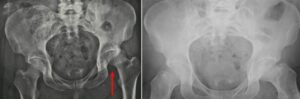

- X-rays, to confirm the position of the dislocated bones.

- CT scans, to detect associated fractures or soft tissue damage.

Treatment

Reduction Procedures

If no other major injuries are present, the doctor will administer an anesthetic or sedative to relax the patient and manually reposition the bones in a process called reduction.

In some cases, reduction must be performed in an operating room under anesthesia. Occasionally, small fragments of bone or torn soft tissues obstruct the femoral head from returning to the socket. When this happens, surgical intervention is necessary to remove debris and correctly align the bones.

After the reduction, the doctor will order follow-up imaging, such as X-rays or a CT scan, to confirm that the bones are properly aligned.

Timely and effective treatment is critical to restoring hip function and preventing long-term complications.

(Left) This X-ray, taken from the front, shows a patient with a posterior dislocation of the left hip. (Right) Normal alignment after the hip has been reduced.

Nonsurgical Treatment

If the hip joint is successfully realigned and no fractures are present in the femoral head (ball) or acetabulum (socket), nonsurgical management may be appropriate. In such cases:

- Weight-bearing on the affected leg is typically restricted for 6 to 10 weeks.

- Patients are advised to avoid specific leg positions that may place strain on the recovering joint.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery becomes necessary if there are fractures associated with the dislocation or if the hip remains unstable after reduction.

The primary goals of surgical treatment are:

- Restoring joint stability.

- Repositioning cartilage surfaces to their normal alignment.

This procedure typically requires a large incision and can result in significant blood loss, often necessitating a blood transfusion during or after the operation.

Complications of Hip Dislocation

- Nerve Injury

- Posterior dislocations may compress or stretch nerves, particularly the sciatic nerve, which extends from the lower back to the legs.

- This nerve injury can lead to weakness in the lower leg and impair movement of the knee, ankle, or foot.

- Sciatic nerve damage occurs in about 10% of patients with hip dislocations, and while most experience some recovery, full recovery is not guaranteed.

- Osteonecrosis (Avascular Necrosis)

- When the femoral head is dislocated, it can tear blood vessels, cutting off blood supply to the bone. This condition, known as osteonecrosis, leads to the death of bone tissue and can cause:

- Severe pain.

- Joint destruction.

- Increased risk of arthritis.

- When the femoral head is dislocated, it can tear blood vessels, cutting off blood supply to the bone. This condition, known as osteonecrosis, leads to the death of bone tissue and can cause:

- Arthritis

- Damage to the cartilage that cushions the joint raises the likelihood of developing arthritis over time. Arthritis can result in significant pain and stiffness, potentially requiring advanced procedures like a total hip replacement in the future.

Recovery and Rehabilitation

Recovery from a hip dislocation typically takes 2 to 3 months, although this timeline may be extended if fractures or other injuries are present. To prevent re-injury, doctors may recommend restricting certain hip movements for several weeks.

- Physical Therapy: Rehabilitation programs focus on restoring strength, flexibility, and mobility.

- Mobility Aids: Patients are usually encouraged to begin walking with aids such as crutches, walkers, or canes as early as possible to promote mobility and healing.

Patience and adherence to the prescribed treatment plan are essential for achieving optimal recovery and minimizing the risk of complications.