Introduction

The increased use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has led to the frequent detection of thoracic disc herniations, with studies estimating that up to 15% of the population may have this condition. However, in many cases, these herniations are incidental findings, appearing on MRI scans conducted for unrelated issues.

Most individuals with thoracic disc herniation remain asymptomatic and do not experience significant problems. When symptoms do occur, the primary concern is whether the herniated disc is compressing the spinal cord. Despite common references to a “slipped disc,” the disc does not actually shift out of place; instead, herniation refers to the protrusion of the central disc material beyond its normal boundary. Thoracic disc herniation is most commonly observed in individuals aged 40 to 60 years.

This guide provides insights into:

• The underlying causes and progression of thoracic disc herniation

• How physicians diagnose the condition

• Available treatment options for managing symptoms

Anatomy of the Thoracic Spine

What Structures Are Involved?

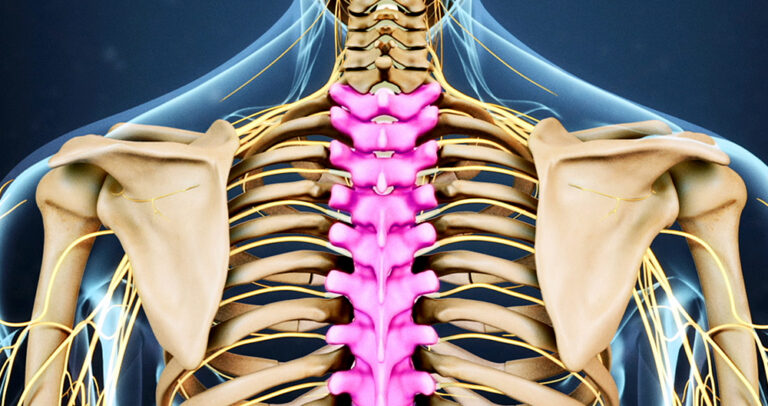

The human spine consists of 24 vertebrae, stacked in a column to form the spinal column. The thoracic spine is composed of 12 vertebrae (T1-T12), extending from the base of the neck to the lower ribcage. The T12 vertebra serves as a transitional point, connecting the thoracic spine to the lumbar spine (L1).

• The upper thoracic spine (T1-T6) is relatively immobile due to its attachment to the ribcage, making disc herniations in this region uncommon.

• The lower thoracic spine (T8-T12) is more flexible and susceptible to mechanical stress, accounting for nearly 75% of thoracic disc herniations, particularly at T11-T12.

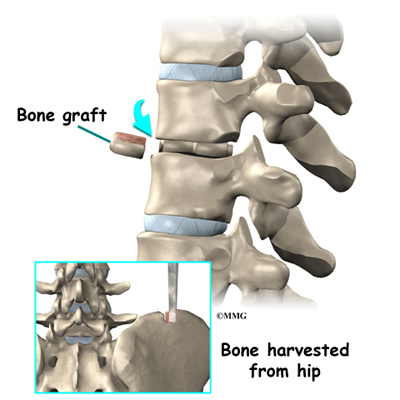

The intervertebral discs between the vertebrae provide shock absorption and stability. Each disc consists of:

• Nucleus pulposus – A gel-like central core responsible for cushioning forces.

• Annulus fibrosus – A strong outer layer of fibrous rings, securing the nucleus in place.

A herniation occurs when the nucleus pulposus protrudes through the annulus fibrosus, leading to compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots.

The Critical Zone: Why Some Herniations Are More Dangerous

The spinal canal houses the spinal cord, which extends through the thoracic spine. Unlike the cervical and lumbar regions, the thoracic spinal canal is narrower, making any space-occupying lesion, such as a herniated disc, a potential risk for spinal cord compression.

A particularly vulnerable region within the thoracic spine is the “critical zone” (T4-T9). This section is supplied by only one blood vessel—the anterior spinal artery. Compression in this area can compromise blood flow, leading to spinal cord ischemia and potential paralysis if untreated.

Causes of Thoracic Disc Herniation

Why Does This Condition Develop?

Thoracic disc herniation primarily results from degenerative changes in the spine. Over time, the intervertebral discs experience wear and tear, leading to:

• Disc dehydration and loss of elasticity, making them more prone to herniation.

• Small tears in the annulus fibrosus, allowing disc material to protrude.

• Progressive degeneration, particularly at T11-T12, due to mechanical forces from bending and twisting.

Other Contributing Factors

In some cases, a herniation may occur suddenly due to acute trauma. These events include:

• High-impact injuries – Such as falls or motor vehicle accidents.

• Repetitive strain – Chronic overuse from activities involving twisting, lifting, or poor posture.

• Pre-existing spinal conditions – Individuals with Scheuermann’s disease have a higher likelihood of multiple thoracic disc herniations.

When a herniation occurs in the critical zone (T4-T9), there is an increased risk of spinal cord injury due to direct compression or reduced blood flow. This can result in significant neurological deficits, including weakness, loss of sensation, and, in severe cases, paralysis.

Symptoms of Thoracic Disc Herniation

What Are the Signs and Symptoms?

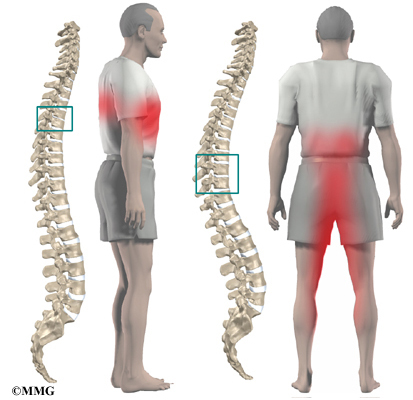

Symptoms of thoracic disc herniation vary based on:

• The location and size of the herniation.

• Whether the disc is compressing the spinal cord or nerve roots.

Common symptoms include:

• Mid-back pain – The most frequent symptom, often worsened by movement, deep breathing, or prolonged sitting.

• Radiating pain – Discomfort may extend to the chest, ribs, or abdomen, sometimes mimicking heart, lung, or gastrointestinal conditions.

• Numbness and tingling – Sensory disturbances can occur along the rib cage or lower extremities.

• Muscle weakness – In cases of spinal cord compression (myelopathy), patients may experience leg weakness, difficulty walking, or even bowel and bladder dysfunction.

Referred Pain: How Thoracic Disc Herniation Mimics Other Conditions

Depending on the level of disc herniation, symptoms may radiate to different parts of the body, making diagnosis challenging:

• Upper thoracic herniations (T1-T5) – May cause pain in the arms, chest, or mimic cardiac symptoms.

• Mid-thoracic herniations (T6-T9) – Can lead to abdominal pain, sometimes mistaken for gastrointestinal issues.

• Lower thoracic herniations (T10-T12) – May result in groin or lower limb pain, resembling kidney disorders.

If the spinal cord is compressed, patients may experience progressive neurological decline, requiring urgent medical evaluation.