The knee, the largest and one of the most intricate joints in the human body, plays a pivotal role in facilitating movement and supporting daily activities.

Knee ligaments are essential connective tissues that link the femur (thighbone) to the tibia (shinbone) and fibula (the slender bone in the lower leg). These ligaments are frequently subjected to sprains or tears, especially during sports or physically demanding activities.

Historically, sustaining injuries to multiple knee ligaments often meant the end of an athlete’s career in competitive sports. However, advancements in medical treatments and rehabilitation techniques now enable many athletes to regain full functionality and even return to high-performance sports after combined ligament injuries.

This modern progress highlights the transformative potential of personalized recovery plans and state-of-the-art surgical interventions.

Anatomy of the Knee Joint

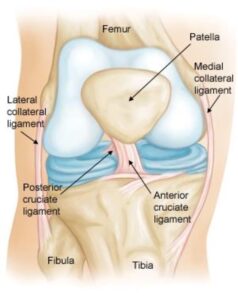

The knee joint is a meeting point for three critical bones: the femur (thighbone), the tibia (shinbone), and the patella (kneecap). Positioned at the front of the joint, the patella provides a protective shield for the underlying structures.

This modern progress highlights the transformative potential of personalized recovery plans and state-of-the-art surgical interventions. The knee features four primary ligaments, which function like sturdy ropes to ensure proper alignment and movement.

- Collateral Ligaments: Located on the sides of the knee, these ligaments manage side-to-side motion and protect the knee from abnormal lateral movements.

- Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL): Found on the inner side of the knee, it connects the femur to the tibia.

- Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL): Positioned on the outer side, it links the femur to the fibula.

- Cruciate Ligaments: Situated within the knee joint, these ligaments form an X-shape, with the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in the front and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) at the back. They regulate the forward and backward motion of the knee.

Normal knee anatomy. The knee is made up of four main things: bones, cartilage, ligaments, and tendons.

Normal knee anatomy. The knee is made up of four main things: bones, cartilage, ligaments, and tendons.

Understanding Knee Ligament Injuries

The knee relies heavily on its ligaments and surrounding muscles for stability, making it prone to injuries. Direct trauma to the knee or abrupt muscular contractions—such as sudden direction changes while running—can lead to ligament damage.

Ligament injuries, commonly known as sprains, are classified into three grades based on severity:

- Grade 1 Sprains: The ligament is slightly stretched and mildly damaged but remains functional, providing stability to the knee joint.

- Grade 2 Sprains: This involves a partial tear of the ligament, causing it to loosen and compromise the joint’s stability.

- Grade 3 Sprains: A complete tear where the ligament is either torn in half or detached from the bone, resulting in significant instability of the knee.

Combined Knee Ligament Injuries and Complications

Injuring multiple ligaments simultaneously can lead to serious complications, including:

- Disruption of Blood Flow: Damage to the ligaments may impair blood supply to the lower leg.

- Nerve Damage: Nearby nerves responsible for muscle control in the limb can be affected.

- Severe Outcomes: In rare cases, extensive damage to multiple ligaments may necessitate amputation.

The MCL is the most frequently injured ligament, often in isolation, but it may also occur alongside ACL tears or other ligament injuries. Conversely, LCL injuries are more commonly associated with damage to other knee structures due to the complex anatomy of the knee’s outer side.

With a clear understanding of knee anatomy and injury mechanisms, prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment are essential to mitigate complications and support recovery.

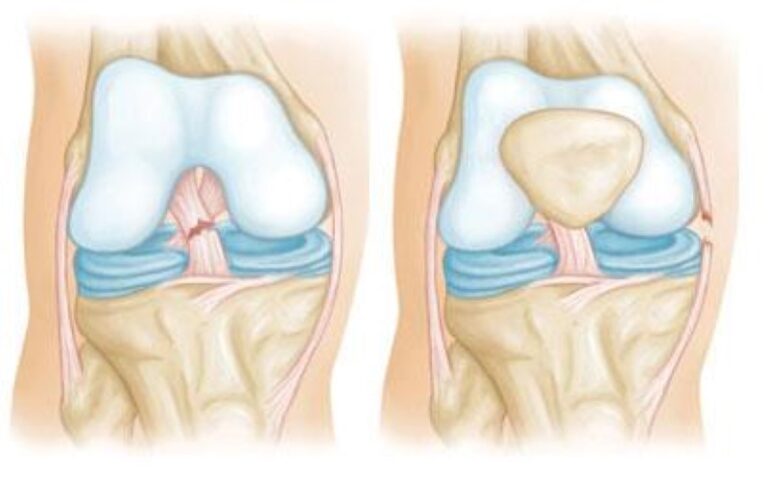

Tears of the anterior cruciate ligament (left) can occur along with injuries to the medial collateral ligament (right).

Treatment Approach

When a multiple ligament injury is suspected, a comprehensive evaluation by an experienced orthopedic specialist is essential. In some cases, the orthopedic surgeon may collaborate with other experts, such as vascular surgeons or microsurgeons, particularly if there are complications involving blood vessels or nerves.

Unlike single ligament tears, surgery for combined ligament injuries is often performed shortly after the injury. Early intervention may be necessary to:

Repair certain ligaments that are more challenging to fix as time passes.

Address vascular injuries that require immediate attention.

However, early surgery for multiple ligament tears carries risks, such as arthrofibrosis, where scar tissue forms within the joint, leading to stiffness. To manage these complexities, treatment may involve multiple procedures, including:

Staged Ligament Reconstruction: Surgery performed in phases to restore knee stability.

Scar Tissue Release: Additional surgery to improve joint mobility if stiffness develops.

This staged approach allows for optimal healing and minimizes long-term complications.

Expected Outcomes

The outcomes for multiple ligament surgery vary and are less predictable compared to single ligament repair. While advancements in surgical techniques have enabled many patients to return to high-level sports, success is not guaranteed.

Improved Prognosis: Unlike the past, where such injuries often marked the end of athletic careers, many individuals now regain significant functionality.

Challenges with Severe Injuries: Cases involving nerve damage may result in permanent weakness in the foot or ankle, potentially impairing athletic performance and daily function.

With the right treatment plan and rehabilitation, patients can maximize their chances of recovery and functional improvement, although outcomes depend on the severity and complexity of the injury.