Introduction to Osteoarthritis of the Ankle

Ankle joint injuries are quite common. While most ankle fractures and sprains heal well, they can sometimes lead to complications later in life. Over time, wear and tear in the joint following an injury can result in a condition known as osteoarthritis (OA) or posttraumatic arthritis. The term “posttraumatic arthritis” specifically refers to arthritis that develops as a consequence of a prior injury (trauma).

This guide provides insights into:

- How arthritis of the ankle develops

- How the condition is diagnosed

- Available treatment options

Anatomy: How Does the Ankle Joint Work?

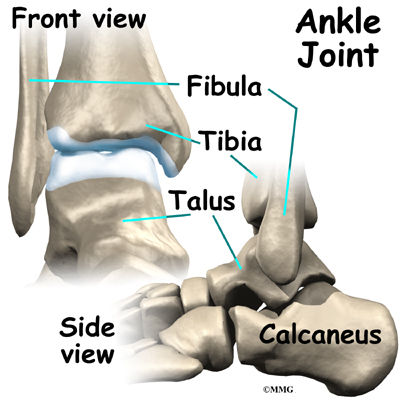

The ankle joint is formed by three primary bones:

- The tibia (shinbone) at its lower end

- The fibula, the smaller bone of the lower leg

- The talus, which fits into the socket formed by the tibia and fibula

Beneath the talus lies the calcaneus (heelbone). The talus primarily functions as a hinge, allowing the foot to move up and down.

Supporting Structures

- Ligaments: Located on both sides of the ankle, these connective tissues stabilize the joint by holding the bones together.

- Tendons: Numerous tendons cross the ankle to facilitate movement of the foot and toes. The Achilles tendon, located at the back of the ankle, is the strongest tendon in the foot. It connects the calf muscles to the heelbone, providing the power needed for walking, running, and jumping.

Articular Cartilage

Inside the ankle joint, the bones are covered with a smooth, slippery material called articular cartilage. This cartilage allows the bones to glide against each other effortlessly. In weight-bearing joints like the ankle, hip, and knee, the cartilage lining is about one-quarter of an inch thick. It is designed to absorb shock and endure a lifetime of use, provided it remains free from injury.

Causes: Why Does Osteoarthritis of the Ankle Develop?

Degenerative Arthritis (OA)

Osteoarthritis (OA) is commonly referred to as wear-and-tear arthritis. Whether it develops years after a joint injury or arises without a history of trauma, OA behaves similarly. Over time, the cartilage in the joint deteriorates, leading to pain and stiffness.

Genetic Factors

Recent studies suggest that OA may have a genetic component, meaning it can run in families. People with certain genetic differences in the chemical makeup of articular cartilage may be more prone to developing OA, even without prior injury.

Injury-Related Causes

Joint injuries, such as severe sprains or fractures, can damage articular cartilage in several ways:

- Bruised Cartilage: Excessive pressure on the cartilage can cause internal damage that may not be immediately visible. Symptoms often develop months later.

- Cartilage Tears: Severe injuries may rip pieces of cartilage from the bone. These fragments cannot reattach themselves and may float within the joint, causing pain, catching sensations, or further damage to the joint surface.

- Scar Tissue Formation: Unlike bone, cartilage does not regenerate. When damaged, the defects are filled with scar tissue, which lacks the durability and smoothness of healthy articular cartilage. Scar tissue cannot support weight effectively and wears out more quickly.

Changes in Joint Mechanics

Even injuries that do not directly damage the cartilage can alter the joint’s biomechanics:

- Fractures: Bones may heal in a way that changes the joint’s alignment or movement.

- Ligament Damage: Injured ligaments can lead to joint instability, increasing stress on the cartilage.

Over time, these changes create an imbalance in the joint’s mechanics, much like an unbalanced machine that wears out faster. This ongoing imbalance gradually damages the articular cartilage. Since cartilage has a limited ability to repair itself, the damage accumulates until the joint can no longer compensate, leading to pain and dysfunction.

Types of Arthritis

Arthritis can develop in two primary ways:

- Genetic or Degenerative OA: Resulting from inherited differences in cartilage composition.

- Post-Traumatic Arthritis: Occurring after an injury that causes progressive damage to joint surfaces.

Regardless of the cause, both types of arthritis result in worn-out joints that eventually become painful. For simplicity, this guide refers to both as osteoarthritis (OA).

Symptoms: What Does Osteoarthritis of the Ankle Feel Like?

The primary symptom of ankle osteoarthritis (OA) is pain, which initially occurs during activity. Over time, the condition progresses, and the nature of the pain changes:

- Early Stages: Pain is often activity-related and tends to subside once movement begins. However, after resting for a few minutes, pain and stiffness can increase.

- Progression: As OA worsens, pain may persist even during rest and can interfere with sleep. The ankle joint may swell, fill with fluid, and feel tight, especially after increased activity.

- Advanced Stages: The wearing away of the articular cartilage can cause the joint to produce a squeaking sound during movement, known as crepitation.

Impact on Joint Function

OA progressively limits joint movement and flexibility:

- Stiffness: The joint may lose its range of motion, making certain movements difficult and painful.

- Instability: Trusting the joint to bear weight becomes challenging. A pain reflex may cause the surrounding muscles to stop working suddenly, increasing the risk of stumbling or falling.

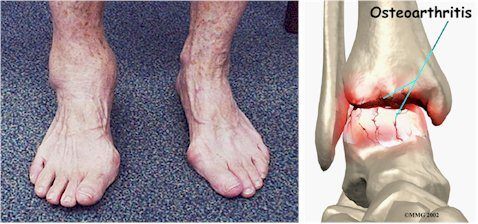

Severe Stage

In advanced cases, the bone beneath the articular cartilage may wear away, leading to:

- Joint Deformities: Misalignment of the bones can create abnormal angles where they meet.

- Structural Changes: These deformities further impair joint function and contribute to chronic pain.

Diagnosis: How Is Osteoarthritis of the Ankle Identified?

The diagnosis of osteoarthritis (OA) begins with a detailed medical history. Your doctor will ask about:

- Past injuries to the joint, even if they occurred years ago, as they may explain the development of OA.

- Whether family members have OA, as genetics can play a role.

After gathering your history, your doctor will conduct a physical examination:

- Assessing the range of motion in the ankle and checking for stiffness or limitations.

- Evaluating the alignment of the ankle joint.

- Examining the nerves and circulation in the legs and ankles.

- Observing your gait to determine if there is a noticeable limp.

Imaging and Tests

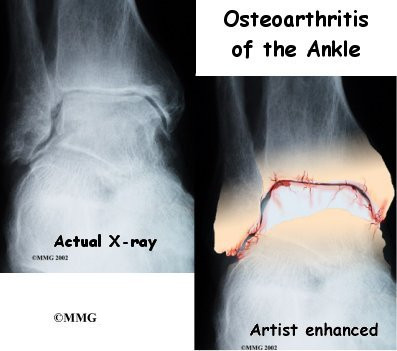

- X-rays: Regular X-rays are the most critical diagnostic tool for assessing the severity of OA. They provide an estimate of how much articular cartilage remains in the joint and reveal other joint damage.

- Blood Tests: If there’s a possibility of another condition causing the arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis, blood tests may be ordered.

- Joint Fluid Analysis: A needle may be used to extract fluid from the joint for lab analysis. This can help detect:

- Crystals associated with gouty arthritis

- Signs of infection

These diagnostic steps help determine the extent of the arthritis and identify any underlying causes, ensuring the appropriate treatment plan is developed.

Treatment: How Can Osteoarthritis of the Ankle Be Managed?

The treatment of ankle osteoarthritis (OA) involves both nonsurgical methods to manage symptoms and surgical procedures for more severe cases. Surgery is typically considered only when nonsurgical options fail to control the symptoms effectively.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Treatment usually begins when ankle pain first occurs. Early symptoms, often triggered by heavy use, may be managed with:

- Mild Anti-inflammatory Medications: Over-the-counter options like aspirin or ibuprofen can help alleviate pain and reduce inflammation.

- Activity Modification: Reducing activities that involve prolonged standing or walking may help control symptoms.

Medications

- Glucosamine and Chondroitin Sulfate: These supplements are increasingly used by orthopedic specialists to reduce OA pain in various joints, including the ankle.

- Injectable Medications: These treatments, which lubricate the joint, are primarily studied in the knee and are not yet commonly prescribed for the ankle.

Rehabilitation and Therapy

Physical therapy plays a vital role in managing ankle OA. Therapy focuses on:

- Controlling symptoms with techniques like rest, heat therapy, and topical rubs.

- Improving flexibility, balance, and strength in the ankle.

- Retraining gait to ensure smooth, pain-free walking, possibly with the use of aids such as walkers, crutches, or canes.

Footwear and Braces

- Rocker Soles: These modified shoe soles have a rounded design that allows the foot to roll smoothly during steps, reducing stress on the ankle.

- Braces:

- Ankle Braces: Limit ankle motion to reduce pain.

- Patellar Tendon Bearing Braces: These specialized braces transfer some body weight to the knee to protect the ankle. However, they are bulky and may not be well-tolerated by all patients.

Cortisone Injections

A cortisone injection into the joint can provide temporary relief from pain and inflammation.

- Effectiveness: Relief typically lasts several weeks to months.

- Risks: As with any joint injection, there is a small risk of infection.

Surgery for Osteoarthritis of the Ankle

When nonsurgical treatments are no longer effective, surgery may become necessary to manage osteoarthritis (OA) of the ankle. The choice of surgical procedure depends on several factors, including:

- The severity of ankle degeneration

- Your activity level and lifestyle

- Your age

- Any existing medical conditions

Your surgeon will evaluate these factors and discuss the risks and benefits of each option to help determine the most suitable procedure for you. Common surgical options include:

- Arthroscopic Surgery

- This minimally invasive procedure involves inserting a small camera and instruments into the joint to clean out debris, remove damaged tissue, and improve joint function.

- Joint Fusion (Arthrodesis)

- In this procedure, the bones of the joint are fused together to eliminate motion and reduce pain. While this can improve stability and alleviate discomfort, it also limits flexibility in the ankle.

- Ankle Replacement (Arthroplasty)

- This involves replacing the damaged joint with an artificial ankle joint. The goal is to preserve mobility while relieving pain. This option is often recommended for patients with severe OA who want to maintain joint movement.

Arthroscopic Debridement

In cases of ankle osteoarthritis (OA), loose cartilage and bone fragments can accumulate inside the joint, causing irritation and inflammation. These loose bodies may also become trapped between joint surfaces, leading to sharp pain. Additionally, the cartilage can become rough, with peeling layers similar to paint flaking off a ceiling. Bone spurs may form around the joint over time, rubbing against soft tissues and causing pain and swelling.

The Procedure

An arthroscope, a small TV camera, is inserted into the joint through tiny incisions (about a quarter of an inch). Surgical tools are introduced through these incisions to:

- Remove loose bodies and bone spurs.

- Smooth the rough cartilage surfaces.

This minimally invasive procedure helps reduce pain and improve joint function by addressing these mechanical issues.

Ankle Fusion (Arthrodesis)

When OA makes walking painful and difficult, ankle fusion surgery may be recommended. This procedure fuses the three main bones of the ankle joint—tibia, fibula, and talus—into a single bone. While this eliminates movement in the ankle, it effectively relieves pain.

Key Considerations

- Post-Surgery Function: Most patients can walk with minimal difficulty after a successful fusion, though running becomes challenging due to the inability to push off with the toes.

- Shoe Modifications: Patients often require shoes with a rocker sole, which helps compensate for the loss of ankle motion and eases walking. A special heel may also be added to absorb shock.

- Durability: Ankle fusion is a long-lasting solution, especially for younger, active individuals. However, complications can occur, and not all fusions are successful.

This procedure is commonly recommended for post-traumatic arthritis of the ankle.

Artificial Ankle Replacement

Efforts to preserve ankle mobility have led to significant advances in artificial ankle replacements. Historically, artificial ankles were less successful than replacements for hips or knees, primarily due to the ankle’s complex anatomy. The tibia and fibula, which form the ankle socket (mortise), move slightly against each other during walking, making it difficult for the artificial joint to remain stable.

Advancements in Design

Newer artificial ankle designs have improved outcomes significantly. Surgeons now often:

- Fuse the tibia and fibula during the procedure, stabilizing the socket.

- Use screws to secure the bones and improve the longevity of the replacement.

These advancements have made artificial ankle replacements a viable alternative to fusion, particularly for patients with post-traumatic arthritis. This procedure preserves ankle motion, avoiding some of the functional limitations associated with fusion.