Rephrased Paragraph:

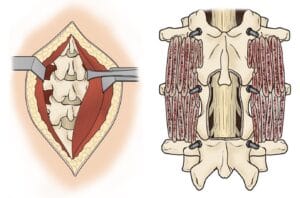

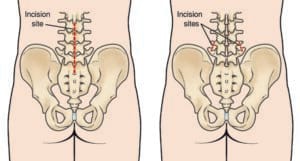

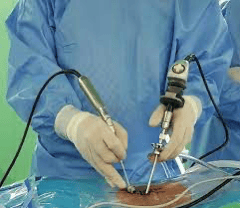

Traditional spine surgery has generally involved “open surgery,” requiring a long incision for the surgeon to fully view and access the spinal area. However, advancements in technology now allow many spine conditions to be managed through minimally invasive surgical techniques (MISS). These techniques achieve similar outcomes to open surgery but involve significantly smaller incisions, which translates to fewer muscle disruptions around the spine.

Compared to the larger incisions in open surgery, minimally invasive spine surgery reduces muscle damage, leading to less postoperative pain and a shorter recovery time. Despite these benefits, MISS can be technically demanding due to the limited access provided by smaller openings, requiring a more specialized skill set for surgeons. The criteria for opting for minimally invasive surgery are the same as those for open procedures.

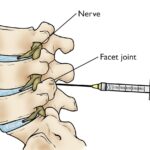

Surgical intervention is generally considered only after nonsurgical treatments, such as medications and physical therapy, fail to alleviate symptoms. Additionally, a precise diagnosis, like a herniated disk or spinal stenosis, must be confirmed before recommending surgery.

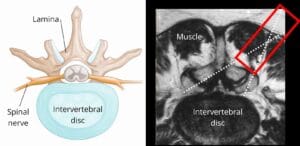

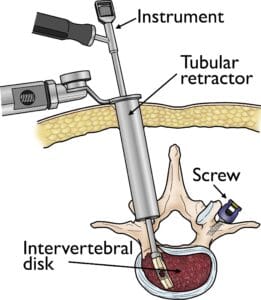

Several minimally invasive techniques exist, all characterized by their use of smaller incisions and reduced muscle impact. These methods are commonly used for lumbar decompression and spinal fusion procedures. Decompression aims to alleviate nerve pressure by removing parts of a herniated disk or bone, while spinal fusion stabilizes painful vertebrae by fusing them into a single solid bone. This article provides an overview of minimally invasive approaches to spinal decompression and fusion.

For an in-depth guide on spinal fusion, covering methods, bone grafting, potential complications, and rehabilitation, see our complete overview on Spinal Fusion.

Description

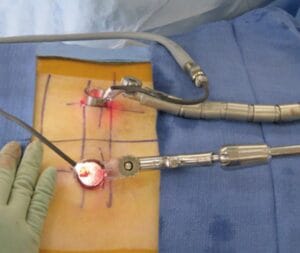

Minimally invasive spine surgery (MISS), sometimes referred to as “less invasive spine surgery,” involves accessing the spine through small incisions with specialized instruments. In contrast to traditional open surgery, which requires a 5- to 6-inch incision, MISS minimizes tissue disruption by eliminating the need to pull muscles aside to view the spine.

In open spine surgery, retracting muscles allows the surgeon to:

- Access the spine to remove damaged bone or intervertebral disks.

- Clearly identify placement points for screws, cages, and bone graft materials to stabilize the spine and aid in healing.