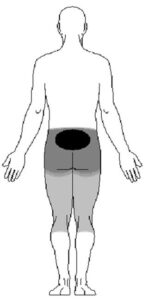

Spondylolysis (pronounced spon-dee-low-lye-sis) and spondylolisthesis (pronounced spon-dee-low-lis-thee-sis) are prevalent sources of lower back pain among children and adolescents.

Spondylolysis occurs when a vertebra — one of the small bones that form the spinal column — develops a weakness or stress fracture. This condition can affect up to 5% of children as young as six, even without any apparent injury. Adolescents involved in sports that put repeated strain on the lower back, such as gymnastics, football, or weightlifting, are at higher risk of developing this type of stress fracture. In certain instances, the fracture significantly weakens the bone, compromising its stability in the spine. When this happens, the affected vertebra may begin to shift or slip from its position, a condition known as spondylolisthesis.

Anatomy of the Spine

The spine consists of 24 small, rectangular vertebrae stacked sequentially to form a protective canal for the spinal cord. The five vertebrae in the lower back make up what is known as the lumbar spine.

Key components of the spine include:

- Spinal Cord and Nerves: These essential “electrical cables” run through the spinal canal, transmitting signals between the brain and muscles. Nerve roots branch from the spinal cord through openings in each vertebra.

- Facet Joints: Located between and behind neighboring vertebrae, these small joints provide spinal stability and help regulate movement. They function like hinges, aligned in pairs along each side of the spine.

- Intervertebral Disks: Flat, round, and about half an inch thick, these flexible disks sit between vertebrae, acting as cushions and absorbing shock from activities like walking or running.

Understanding Spondylolysis and Spondylolisthesis

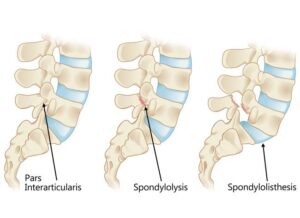

Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are distinct spinal conditions often closely related.

Spondylolysis Spondylolysis refers to a crack or stress fracture in the pars interarticularis, a narrow section of the vertebra connecting the upper and lower facet joints. This fracture most frequently affects the fifth vertebra in the lumbar spine, though it can also occur in the fourth. The fracture may be unilateral or bilateral.

The pars interarticularis is the vertebra’s most vulnerable area, particularly susceptible to repetitive stress and overuse, common in high-impact sports. Although spondylolysis often affects young athletes, it can develop in people of all ages without any sports-related activity.

Many patients with spondylolysis also experience some degree of spondylolisthesis.

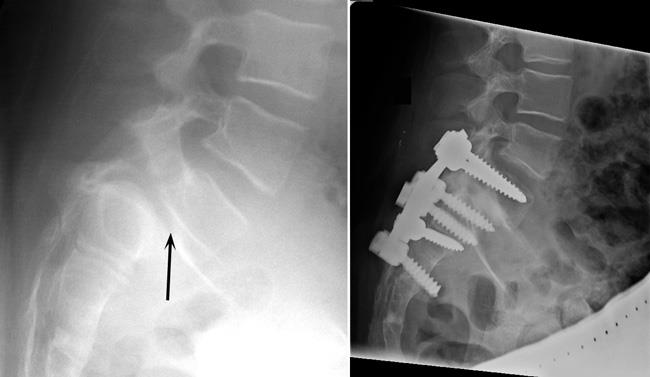

Spondylolisthesis In spondylolisthesis, the fractured pars interarticularis separates, allowing the affected vertebra to slip forward over the vertebra directly below it. This slippage often occurs during periods of rapid growth, such as an adolescent growth spurt.

Doctors classify spondylolisthesis as either low-grade or high-grade based on the extent of slippage. High-grade spondylolisthesis, where more than 50% of the fractured vertebra shifts forward, often results in greater pain and nerve-related symptoms, potentially necessitating surgery to alleviate discomfort and prevent further progression.