Lumbar spinal canal narrowing is a frequent source of lower back pain and leg discomfort, often leading to sciatica symptoms.

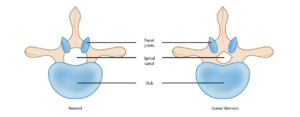

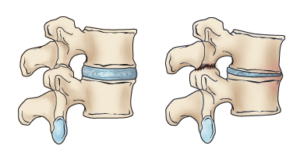

As the body ages, natural wear-and-tear can gradually reduce the width of the spinal canal, which encases the spinal nerves and spinal cord—a condition known as spinal stenosis. Degenerative spinal changes are common, appearing in as many as 95% of individuals by age 50, and lumbar spinal stenosis predominantly affects adults over 60. Both men and women experience similar rates of nerve root compression.

In rare cases, some individuals are born with spinal structures that predispose them to lumbar spinal stenosis, referred to as congenital spinal stenosis. This typically occurs in people with a naturally smaller spinal canal, where restricted space makes them more susceptible to early degeneration or arthritis. This form of stenosis is more common in men, with symptoms generally beginning between ages 30 and 50.

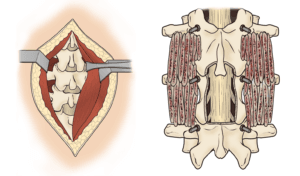

Anatomy

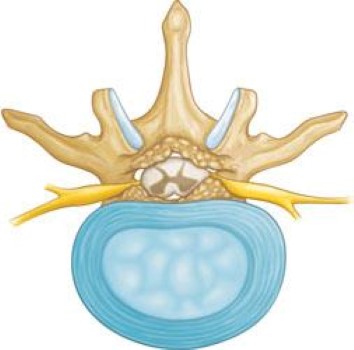

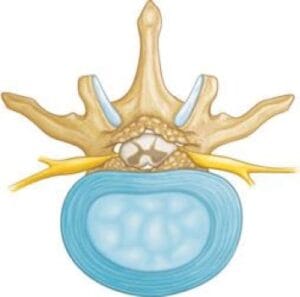

The spine consists of a series of small bones, called vertebrae, stacked along the back to form a sturdy column. Alongside these vertebrae, the spine comprises muscles, ligaments, nerves, and intervertebral discs, all essential for stability, flexibility, and protection.

A basic understanding of spine structure and function is key to grasping spinal stenosis. For an overview of spine anatomy, visit our section on Spine Basics.

Description

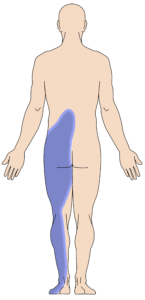

Spinal stenosis develops when the space surrounding the spinal cord and nerves becomes restricted. This narrowing can place pressure on the spinal cord and nerve roots, often resulting in pain, numbness, or leg weakness.