Rephrased Section on Congenital Kyphosis:

Congenital kyphosis is a spinal condition present at birth, arising from abnormal spinal column development during fetal growth. This condition may result from vertebrae that do not form correctly or from multiple vertebrae that are fused together. Congenital kyphosis commonly progresses as the child grows.

Children with congenital kyphosis often require surgical intervention at a young age to halt further curve progression. Additionally, many children with this condition have other congenital anomalies affecting various body systems, such as the heart and kidneys.

This rephrased content maintains scientific accuracy and incorporates SEO phrases like “congenital kyphosis,” “spinal development,” and “surgical intervention for congenital kyphosis.” Let me know if you’d like further adjustments!

(Left) Clinical photo of a child with congenital kyphosis in his thoracic spine. (Right) A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of his spine shows spinal cord compression. This can lead to neurological symptoms like weakness and numbness in the legs.

Rephrased Symptoms Section:

The symptoms of kyphosis can vary widely depending on the underlying cause and the severity of the spinal curve. Common signs and symptoms may include:

- Rounded shoulders

- A noticeable hump on the back

- Mild back pain

- Fatigue

- Spinal stiffness

- Tightness in the hamstrings (muscles at the back of the thigh)

In rare cases, progressive kyphotic curves can lead to additional symptoms over time, such as:

- Weakness, numbness, or tingling sensations in the legs

- Loss of sensation

- Changes in bowel or bladder function

- Shortness of breath or breathing difficulties

Rephrased Doctor Examination Section:

Mild kyphosis can often go unnoticed until a routine scoliosis screening at school leads to a referral to a doctor. However, when visible changes in the patient’s back become apparent, it can be distressing for both the child and the parents, often prompting concerns about the back’s cosmetic appearance and a visit to a healthcare provider.

Rephrased Physical Examination Section:

During the initial consultation, the doctor will review your child’s medical history and inquire about their overall health and specific symptoms. The examination begins with an assessment of your child’s spine, where the doctor will press along the back to identify any tender areas.

In this exam, your child will be asked to bend forward with feet together, knees straight, and arms relaxed at the sides. This test, known as the Adam’s forward bend test, helps the doctor observe the spine’s slope and identify any deformity. Additionally, the doctor may have your child lie down to check if the curve straightens—a sign that the kyphosis may be flexible, often indicating postural kyphosis.

This revision is designed with SEO in mind, emphasizing keywords like “kyphosis symptoms,” “doctor examination for kyphosis,” and “Adam’s forward bend test.” Let me know if you’d like further edits!

To assess for a curve, your doctor will ask your child to bend forward at the waist.

Rephrased Tests Section:

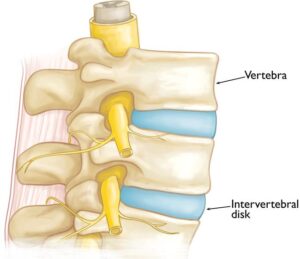

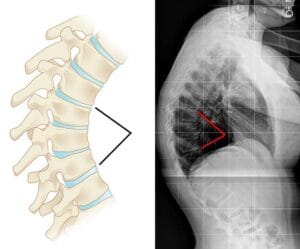

X-rays: X-rays are commonly used to capture images of dense structures like bones. Your doctor may request X-rays from multiple angles to examine the vertebrae for any structural abnormalities and determine the degree of the kyphotic curve. Curves exceeding 50 degrees are considered outside the normal range, though this doesn’t necessarily imply a need for invasive treatment.

Pulmonary Function Tests: For more severe curves, the doctor may recommend pulmonary function tests to evaluate any potential impact on lung function due to reduced chest space.

Additional Tests: In cases of congenital kyphosis, progressive curvature can lead to symptoms of spinal cord compression, including pain, tingling, numbness, or weakness in the lower limbs. If these symptoms arise, or if the curve changes significantly over time, neurologic testing or an MRI scan may be recommended to assess the spinal cord’s condition.

Rephrased Treatment Section:

The primary goal of treatment for kyphosis is to halt curve progression and prevent spinal deformity. Your doctor will consider several factors in developing a treatment plan, including:

- Your child’s age and general health

- Remaining years of growth

- The type of kyphosis

- The curve’s severity

Rephrased Nonsurgical Treatment Section:

Nonsurgical treatment is typically advised for individuals with postural kyphosis and for those with Scheuermann’s kyphosis whose curves are below 70 to 75 degrees.

Nonsurgical approaches may include:

- Observation: For some cases, regular monitoring is sufficient. The doctor may schedule follow-up visits and X-rays to ensure the curve does not worsen until the child reaches skeletal maturity. If the curve remains stable and does not cause pain, no further treatment may be necessary.

- Physical Therapy: Targeted exercises can help alleviate back pain and improve posture by strengthening core and back muscles. Stretching exercises may also help release tight hamstrings, supporting better alignment.

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Medications like ibuprofen, aspirin, or naproxen can help reduce back pain.

- Bracing: For growing patients with Scheuermann’s kyphosis, bracing may be recommended. The type of brace and the recommended daily wear time depend on the curve’s severity. The doctor will adjust the brace periodically as the curve improves. Typically, the brace is worn until the child reaches full skeletal maturity.

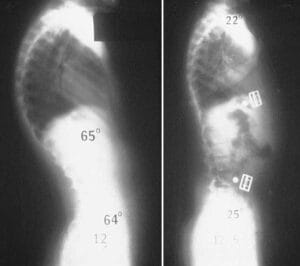

(Left) This patient has a 65-degree curve in the thoracic spine. (Right) Although it cannot be seen on X-ray, the patient is now wearing a back brace that has helped to reduce the excessive curve.

Rephrased Surgical Treatment Section:

Surgery is frequently recommended for individuals with congenital kyphosis, especially to prevent curve progression and associated complications.

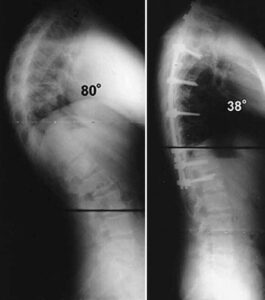

Surgical intervention may also be advised for patients with Scheuermann’s kyphosis when the spinal curve exceeds 70 to 75 degrees or in cases where severe back pain is present. Those with kyphosis in the lower back (thoracolumbar region) may require surgery even for smaller curves, typically above 25 to 30 degrees.

The most common surgical method for treating kyphosis is spinal fusion.

The primary objectives of spinal fusion are to:

- Decrease the curvature

- Prevent further curvature progression

- Ensure long-term stability of the correction

- Relieve significant back pain if it exists

Rephrased Surgical Procedure Section:

Spinal fusion functions like a “welding” process in which the affected vertebrae are fused, allowing them to heal into a single, solid structure. By stabilizing these vertebrae, the procedure reduces the degree of curvature and can alleviate back pain by eliminating motion between the affected vertebrae.

During surgery, the doctor typically uses metal rods and screws to realign the vertebrae. The goal is often to achieve a safe, partial correction—reducing the curve’s magnitude without always aiming for a fully straightened spine. Ideally, the procedure reduces the curvature by about 50% of its original angle. After alignment, small bone fragments, or bone grafts, are placed between the vertebrae to facilitate fusion. Over time, these bones grow together, similar to how a broken bone heals.

The extent of the spine that is fused depends on the curvature’s size. Only the affected vertebrae are fused, leaving the remaining spinal bones free to move, allowing for bending, straightening, and rotation. For larger curves, more vertebrae may need to be fused, resulting in fewer mobile segments for flexibility in bending and twisting

(Left) Preoperative X-ray of a 17-year-old boy with a painful 80-degree curve caused by Scheuermann’s kyphosis. (Right) After spinal fusion and stabilization with plates and screws, the curve has been reduced to 38 degrees.

If kyphosis is diagnosed early, many patients can be treated successfully without surgery and go on to lead active, healthy lives. However, curve progression could potentially lead to problems during adulthood. Patients with kyphosis need regular to monitor the condition and check progression of the curve, whether or not it is treated with surgery.