Neck pain is a prevalent condition that often prompts individuals to seek medical attention. Rather than stemming from a single injury, neck pain commonly develops gradually due to the wear and tear associated with daily activities. Over time, this ongoing strain can lead to the degeneration of the spinal structures, which ultimately becomes a source of discomfort.

Understanding the normal mechanics of your neck and the reasons behind your pain is crucial for effective self-care and management. Patients who are well-informed about their condition tend to feel less anxious and more confident in making decisions about their treatment options.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of neck pain, aiming to help you:

- Learn about the structure and function of the neck and spine

- Identify common causes of neck pain

- Understand diagnostic tests your doctor might recommend

- Discover strategies to reduce pain and improve mobility

By addressing these aspects, you can take proactive steps toward managing neck pain effectively.

Anatomy

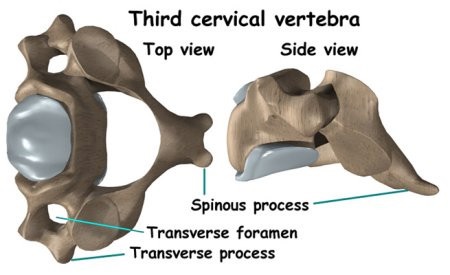

The cervical spine, a critical section of the human spinal column, plays a key role in supporting the head and enabling neck movement. The spine comprises 24 vertebrae, stacked to form the spinal column, which serves as the primary structural support for the body. The first seven vertebrae make up the cervical spine, labeled C1 to C7 by medical professionals. This region begins at the junction of the skull and the top vertebra (C1) and extends downward to where the seventh vertebra (C7) connects with the thoracic spine at the chest.

Each vertebra consists of a round bone block, known as the vertebral body, with a bony ring attached to its back. These rings form a protective hollow tube when stacked, housing the spinal cord as it descends from the brain through the spine. Much like the skull shields the brain, the vertebrae safeguard the spinal cord. Nerve roots branch off the spinal cord between the vertebrae, forming the body’s intricate electrical system. In the cervical spine, these nerves primarily control the arms and hands, while nerves from the thoracic and lumbar spines supply the chest, abdomen, legs, and feet.

To better understand the cervical spine’s structure, it helps to examine a spinal segment. A typical segment includes two vertebrae separated by an intervertebral disc, nerve roots exiting at that level, and small facet joints that connect the vertebrae. Intervertebral discs, composed of specialized connective tissue, act as shock absorbers. These discs are made of collagen fibers, arranged like cloth or ropes, which provide flexibility and resilience. The disc has two parts: the spongy nucleus at its center, which absorbs shocks, and the annulus, a strong ligament ring encasing the nucleus.

Facet joints, found between each pair of vertebrae, are small bony structures along the spine’s back. These joints enable smooth neck movements, such as bending and turning, thanks to articular cartilage—a slick, rubbery material covering the joint surfaces. This cartilage minimizes friction, allowing pain-free motion.

Lastly, spinal nerves exit on both sides of each segment through neural foramina, small bony openings that allow nerve roots to pass from the spinal cord to various parts of the body. This intricate system of bones, joints, discs, and nerves enables the cervical spine to support and protect while maintaining flexibility and function.

Causes

What Causes Neck Pain?

Neck pain can arise from various factors, and identifying the exact source is not always possible. Your doctor will work diligently to rule out serious conditions like cancer or spinal infections as the cause of your symptoms. Below are some of the most common causes of neck pain:

Spondylosis

Most neck pain stems from years of gradual wear and tear on the cervical spine. Initially, these minor injuries are painless, but over time, they accumulate and lead to discomfort. This degeneration, commonly referred to as spondylosis, can affect both the bones and soft tissues of the spine. It’s important to note that spondylosis is often a natural part of the aging process and not necessarily a sign of severe illness.

Degenerative Disc Disease

Aging also brings changes to the intervertebral discs. Repeated stress weakens the connective tissues in the disc, and the central nucleus begins to dry out, reducing its ability to absorb shock. The outer annulus may develop small cracks and tears, and while many of these changes are painless, larger tears can cause neck pain. The body attempts to repair these cracks with scar tissue, but this tissue is weaker and less resilient than the original. Over time, the disc may lose its ability to cushion the spine, leaving it more susceptible to further damage from gravity and daily activities.

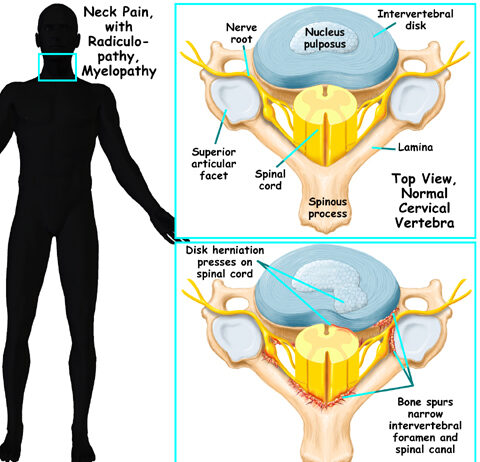

As the disc degenerates, the space between vertebrae narrows, putting pressure on the facet joints. This increased stress damages the articular cartilage in these joints, potentially leading to arthritis. Degenerative changes in discs, facet joints, and ligaments can loosen and destabilize spinal segments, amplifying wear and tear. The weakened annulus may eventually rupture, allowing the nucleus to push into the spinal canal. This condition, known as a herniated or ruptured disc, can compress spinal nerves and release chemicals that cause inflammation, resulting in pain.

Bone Spurs and Nerve Compression

As degeneration progresses, bone spurs often develop around the facet joints and discs. While their exact cause is uncertain, many experts believe these spurs form as the body’s response to stabilize the spine. However, they can press on nerves as they exit the spinal canal through the neural foramina, leading to symptoms such as neck pain, numbness, and weakness in the arms and hands. This combination of nerve irritation and inflammation contributes to the discomfort associated with neck pain.

By understanding the underlying causes, patients can take informed steps toward managing neck pain effectively.

Understanding Neck Pain and Its Causes

Minor neck pain or stiffness is often attributed to a muscle strain. However, unless there has been a significant injury to the neck, it’s unlikely that the muscles themselves are damaged. Instead, the pain may result from irritation or injury to other spinal tissues, such as discs or ligaments. In such cases, neck muscles may go into spasm to stabilize and protect the affected area.

Mechanical Neck Pain

Mechanical neck pain arises from wear and tear in the structures of the neck, similar to the aging of a machine’s components. This type of pain is typically caused by degenerative changes in the discs. As the discs deteriorate and collapse, the space between vertebrae narrows, potentially inflaming the facet joints. Mechanical neck pain is generally chronic, meaning it develops gradually and persists over time.

The discomfort is often localized to the neck but may radiate to the upper back or outer shoulder. Unlike nerve-related pain, mechanical neck pain does not typically result in numbness or weakness in the arms or hands because it does not involve spinal nerve compression.

Cervical Radiculopathy (Pinched Nerve)

When pressure or irritation affects the nerves in the cervical spine, it can disrupt their electrical signals. This may manifest as numbness in the skin, muscle weakness, or sharp pain along the nerve’s pathway. Commonly referred to as a “pinched nerve,” this condition is medically known as cervical radiculopathy.

Several factors can lead to cervical radiculopathy, including degeneration, herniated discs, and spinal instability:

- Degeneration: Aging causes the discs to lose water content and collapse, narrowing the space between vertebrae. This added pressure can inflame and enlarge the facet joints, potentially compressing nerves as they exit through the neural foramina. Bone spurs, another common result of degeneration, can also press on nerves, contributing to radiculopathy symptoms.

- Herniated Disc: Repetitive heavy lifting, bending, and twisting can place excessive pressure on the disc’s nucleus. If this pressure damages the outer annulus, the inner nucleus can protrude, leading to a herniated disc. As the annulus weakens with age, it is more prone to cracking and tearing, increasing the likelihood of herniation.

When herniated disc material compresses a nerve root, it can cause pain, numbness, or weakness in the areas served by that nerve. This condition, known as cervical radiculopathy, is often accompanied by inflammation triggered by chemicals released from the damaged disc. In severe cases, if the herniation compresses the spinal cord, it can result in cervical myelopathy, a more serious condition affecting multiple nerves throughout the spinal cord.

By understanding these causes, patients can work with their healthcare providers to identify the source of their neck pain and pursue effective treatments.

Spinal instability occurs when there is excessive movement between the vertebrae in the spine. In the cervical spine, this instability can result from stretched or torn ligaments caused by a severe neck or head injury. Certain medical conditions that weaken connective tissues can also contribute to spinal instability. Another form of instability involves a vertebral body slipping forward over the one below it, a condition known as spondylolisthesis.

Regardless of the cause, this abnormal movement can irritate or compress the nerves in the neck, leading to symptoms such as pain, numbness, or weakness. Recognizing and addressing spinal instability is crucial to prevent further complications.

Spinal Stenosis and Cervical Myelopathy

Spinal stenosis refers to the narrowing of the spinal canal, which results in compression of the spinal cord. This condition often arises from degenerative changes, such as bone spurs impinging on the spinal cord within the canal. However, spinal stenosis can also occur at any age due to a herniated disc pressing into the spinal canal.

When the spinal cord is compressed in the neck, the condition is known as cervical myelopathy, a serious medical issue requiring prompt attention. Symptoms of cervical myelopathy may include difficulties with bowel and bladder control, changes in gait, and reduced dexterity in the fingers and hands. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential to prevent long-term damage.

By understanding these conditions, individuals experiencing neck pain can seek timely medical care to address the underlying causes and improve their quality of life.

Common Symptoms of Neck Problems

The symptoms of neck problems can vary widely depending on the underlying condition and the specific structures of the neck that are affected. Below are some of the most common symptoms associated with neck issues:

- Neck pain: A primary indicator of many neck conditions.

- Headaches: Often resulting from tension or nerve-related issues in the cervical spine.

- Radiating pain: Discomfort that spreads to the upper back or travels down the arm.

- Stiffness and limited range of motion: Difficulty moving the neck due to tightness or discomfort.

- Muscle weakness: Weakness in the shoulder, arm, or hand caused by nerve compression.

- Sensory changes: Numbness, tingling, or prickling sensations in the forearm, hand, or fingers.

If you experience any of these symptoms, especially when they persist or worsen, it’s important to consult a healthcare professional to determine the cause and receive appropriate treatment. Identifying symptoms early can help prevent further complications and improve outcomes.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing neck problems begins with a detailed review of your medical history and symptoms. You may be asked to complete a questionnaire to provide specific details about your condition. During your consultation, your doctor will ask about the onset of your symptoms, factors that worsen or improve them, and how these issues impact your daily activities. These insights help guide the physical examination.

Next, your doctor will examine the muscles and joints in your neck. This assessment includes checking neck alignment, observing its range of motion, and identifying areas of discomfort.

Simple neurological tests may also be conducted to evaluate the function of your nerves. These tests assess arm and hand strength, reflexes, and the presence of numbness or tingling in your arms, hands, or fingers.

The information gathered from your medical history and physical examination helps your doctor determine which diagnostic tests are necessary. Each test provides valuable information to pinpoint the cause of your neck problem and guide appropriate treatment.

Radiological Imaging for Neck Problems

Radiological imaging plays a crucial role in helping doctors visualize the structure of the spine and diagnose neck issues. Different imaging tests provide specific insights:

X-rays

X-rays are commonly used to detect bone-related problems, including infections, tumors, or fractures. They also help assess spinal degeneration by showing the space between discs and in the neural foramina. As the initial imaging test, X-rays are often performed before more advanced procedures. Special flexion and extension X-rays may be ordered to evaluate spinal instability. These images are taken as you bend forward and backward, allowing your doctor to assess the motion between spinal segments.

MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging)

MRI scans use magnetic waves to produce detailed images of the cervical spine in cross-sectional slices. Unlike X-rays, MRI provides a clear view of not only the spinal bones but also the surrounding soft tissues, including discs, joints, and nerves. This makes MRI particularly valuable for diagnosing issues such as disc herniation or nerve compression.

By using these imaging techniques, doctors can gain a comprehensive understanding of the spine’s anatomy and identify the root cause of neck pain.

CT Scan (Computed Tomography)

A CT scan is a specialized form of X-ray that generates detailed cross-sectional images of bone tissue. Using a computer and X-rays, this test is particularly useful for identifying problems in the bones, such as fractures or structural abnormalities.

Myelogram

A myelogram is a diagnostic procedure that involves injecting a special dye into the spinal sac. The dye enhances X-ray images, making it easier to detect conditions like herniated discs, spinal cord compression, nerve pressure, or tumors. Before the advent of CT and MRI, the myelogram was the primary test for diagnosing herniated discs. Although less common today, myelograms are sometimes combined with CT scans for greater diagnostic detail.

Bone Scan

A bone scan is a specialized test that uses radioactive tracers to identify areas of rapid bone repair, such as those associated with healing fractures, infections, or tumors. The tracers are injected into the bloodstream and highlight active bone activity on imaging. Bone scans are typically used to locate a problem area, which is then further examined with a CT or MRI scan

These imaging tests offer complementary insights, enabling doctors to accurately diagnose neck problems and develop tailored treatment plans.

Additional Diagnostic Tests

Electromyogram (EMG)

An electromyogram (EMG) is a diagnostic tool used to assess nerve function in the upper limbs. This test is particularly helpful in identifying whether nerve roots are being compressed by a herniated disc. During the procedure, small needles are inserted into specific muscles connected to each nerve root. The electrical signals from the muscles are then measured to detect any changes in nerve function, helping to pinpoint which nerve root is affected.

Laboratory Tests

Not all neck pain stems from degenerative spine conditions. Blood tests can be used to identify other potential causes, such as arthritis or infections. These tests help rule out conditions unrelated to the spine, ensuring accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Treatment Options for Neck Pain

Nonsurgical Treatments

Doctors often prioritize nonsurgical methods to alleviate neck pain and related symptoms. These treatments focus on relieving pain, improving mobility, and encouraging healthy posture to slow degeneration and restore normal activity.

- Medications: Pain relievers, anti-inflammatory drugs, and sleep aids may be prescribed to manage symptoms, though they do not cure neck pain.

- Soft Neck Collar: A soft neck collar may be recommended for short-term use to immobilize the neck, allowing muscles and joints to rest and reduce pain, inflammation, and spasms.

- Ice and Heat Applications: Alternating between cold and hot packs can help manage pain and inflammation. Cold packs are applied for 10–15 minutes, or contrast therapy may be used to alternate between cold and heat.

- Physical Therapy: A physical therapist may design a rehabilitation program to reduce pain, improve neck movement, and promote healthy posture. Therapy focuses on preventing future issues while addressing current symptoms.

Injections

Spinal injections are both diagnostic and therapeutic, delivering medications directly to the source of pain. Common injection types include:

- Epidural Steroid Injection (ESI): Medication is injected into the epidural space around nerve roots to reduce pain and inflammation. ESIs are usually considered when other treatments fail.

- Selective Nerve Root Injection: A targeted injection using fluoroscopy to deliver medication to an inflamed nerve root, relieving localized pain and aiding in diagnosis.

- Facet Joint Injection: Used to diagnose and treat facet joint pain by injecting medication into the joint.

- Trigger Point Injection: An anesthetic and cortisone mixture is injected into muscles or soft tissues near the spine to relieve muscle spasms and tenderness.

Surgical Treatments

Surgery is generally considered only after nonsurgical methods have been tried for at least three months unless symptoms indicate serious conditions like spinal cord pressure or rapidly worsening muscle weakness.

- Foraminotomy: Enlarges the neural foramen to relieve nerve compression caused by bone spurs or inflammation.

- Laminectomy: Removes part or all of the lamina to reduce spinal cord pressure from herniated discs or bone spurs.

- Discectomy: Removes a damaged disc, often combined with cervical fusion for stability.

- Cervical Fusion: Joins two or more vertebrae to stabilize the spine, alleviate nerve pressure, and treat conditions like cervical radiculopathy and instability.

- Anterior Discectomy and Fusion: Performed through the front of the neck, often with a bone graft to support fusion.

- Posterior Fusion: Uses bone grafts placed over the back of the spine, primarily for fractures.

- Corpectomy with Strut Graft: Removes vertebral bodies and replaces them with bone graft material to relieve widespread spinal cord compression.

Rehabilitation After Treatment

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Physical therapy often lasts two to four weeks and focuses on relieving pain, improving neck function, and teaching long-term strategies to protect the neck. Patients may be given regular exercises to maintain neck health and prevent future problems.

With consistent care, nonsurgical treatments can delay the need for surgery and improve quality of life.

Rehabilitation After Neck Surgery

Rehabilitation following neck surgery is often more complex and tailored to the patient’s specific needs. The recovery process can vary depending on the type of surgery performed.

Some patients are discharged from the hospital shortly after surgery, while others may need to stay for a few days. During their hospital stay, patients often work with a physical therapist to learn how to move and perform daily activities without placing unnecessary strain on their neck.

Once discharged, many patients continue physical therapy on an outpatient basis for one to three months, depending on the surgery. Therapy sessions are designed to:

- Reduce pain and muscle spasms

- Teach safe movement techniques

- Improve strength and mobility

As therapy progresses, the physical therapist may assist patients in transitioning back to work or other daily activities. For those returning to physically demanding jobs, a work assessment may be conducted to ensure they can perform their duties safely. If needed, therapists can recommend modifications to work tasks or lifestyle habits to prevent future complications and maintain long-term spinal health.

Rehabilitation is an essential part of recovery, helping patients regain functionality while minimizing the risk of reinjury.