Introduction

The wrist joint is one of the most intricate structures in the human body, comprising multiple bones and joints that work together to provide mobility and strength. This complexity allows for a wide range of motion, essential for hand function, while also ensuring stability for gripping and weight-bearing activities.

This guide will help you understand:

• The anatomical components of the wrist

• How these structures function together

Key Structures of the Wrist

The wrist consists of several critical anatomical components, which can be categorized into:

• Bones and joints

• Ligaments and tendons

• Muscles

• Nerves

• Blood vessels

Bones and Joints

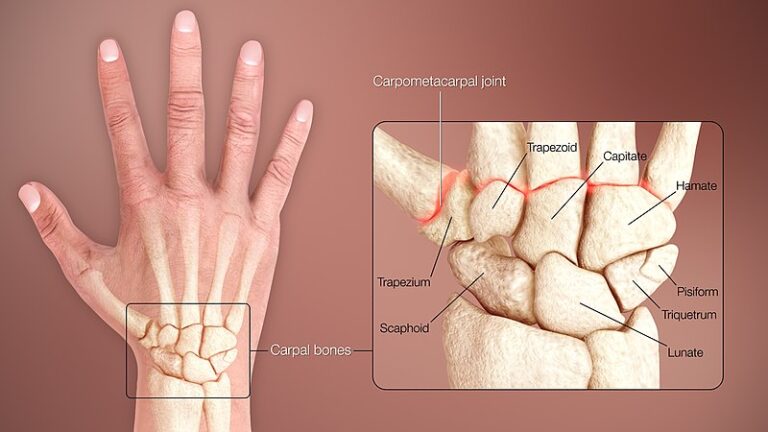

The wrist is composed of 15 interconnected bones that link the forearm to the hand. These include eight small carpal bones, which are divided into two rows:

• Proximal row (closer to the forearm) – Scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum

• Distal row (closer to the hand) – Trapezium, trapezoid, capitate, hamate, and pisiform

These carpal bones connect with the radius and ulna, the two bones of the forearm, andmetacarpal bones of the hand. The metacarpals then attach to the **phalanges, the bones that form the fingers and thumb.

Due to these multiple bone-to-bone articulations, the wrist is not a single joint but a complex system of small joints working in coordination to enable move

Articular Cartilage and Joint Function

The articular cartilage lines the surfaces of these joints, acting as a shock absorber and providing a smooth, frictionless surface for movement. While articular cartilage in major weight-bearing joints is thick, it is thinner in the wrist since it does not support significant loads.

This cartilage covers the contact points of the carpal bones, radius, ulna, and metacarpals, facilitating seamless motion an

Ligaments and Tendons

Ligaments are connective tissues that link bones together, forming a joint capsule—a sealed, fluid-filled sac that encases the joint and contains synovial fluid, which lubricates and nourishes the joint surfaces. In the wrist, the eight carpal bones are enclosed and stabilized by this joint capsule, along with numerous supporting ligaments.

Collateral Ligaments of the Wrist

Two key ligaments, known as collateral ligaments, reinforce the sides of the wrist:

• Ulnar Collateral Ligament (UCL) – Positioned on the ulnar side of the wrist (opposite the thumb), this ligament originates at the ulnar styloid (a small bony prominence on the distal ulna) and extends to both the pisiform and transverse carpal ligament. Another portion of the UCL attaches to the triquetrum, another small carpal bone near the ulnar side. The UCL plays a crucial role in stabilizing the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC)—a key structure that cushions the joint where the ulna meets the wrist and prevents excessive radial deviation (movement toward the thumb side).

• Radial Collateral Ligament (RCL) – Found on the thumb side of the wrist, the RCL originates from the radial styloid and extends to the scaphoid, a carpal bone at the base of the thumb. This ligament restricts ulnar deviation (bending toward the little finger) and enhances wrist stability.

The wrist’s structural complexity arises from the multitude of ligaments interconnecting the carpal bones. If these ligaments become stretched, torn, or weakened—often due to injury or repetitive stress—they can compromise joint integrity and contribute to wrist instability and arthritis.

Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex (TFCC)

The TFCC is a cartilage-based structure situated between the ulna and the lunate and triquetrum bones. It serves as a shock absorber and enhances the gliding motion of the wrist joint. Injury to the TFCC can lead to pain, instability, and reduced wrist function.

Tendons of the Wrist

Tendons attach muscles to bones, allowing movement by transmitting muscular force. The tendons crossing the wrist originate from muscles located in the forearm.

Flexor Tendons (Palm Side of the Wrist)

These tendons bend the fingers, thumb, and wrist. They pass beneath the transverse carpal ligament, a thick band of fibrous tissue on the palm side of the wrist. The transverse carpal ligament prevents the flexor tendons from bowing outward during flexion movements.

Extensor Tendons (Back of the Wrist)

Extensor tendons travel over the dorsal (back) side of the wrist and are enclosed within specialized compartments lined with tenosynovium. This slick lubricating tissue reduces friction, allowing smooth tendon movement.

Muscles of the Wrist

The primary wrist muscles originate in the forearm and extend their tendons across the wrist to control the fingers, thumb, and wrist movements. These muscles are functionally divided into:

• Flexors – Located on the palm side, these muscles enable gripping and wrist flexion.

• Extensors – Located on the dorsal side, these muscles facilitate wrist extension and finger straightening.

Nerves of the Wrist

All nerves supplying the hand and fingers pass through the wrist, playing a crucial role in motor function and sensation. The three primary nerves—radial nerve, median nerve, and ulnar nerve—originate from the shoulder and extend down the arm. These nerves control hand movements and transmit sensory information such as touch, temperature, and pain back to the brain.

Radial Nerve

The radial nerve runs along the thumb-side (lateral edge) of the forearm, wrapping around the radius bone before extending to the back of the hand. It provides sensation to the dorsal (back) surface of the thumb, index, and middle fingers, as well as the proximal portion of the ring finger. This nerve is responsible for wrist and finger extension, allowing for actions such as straightening the fingers and lifting the wrist.

Median Nerve

The median nerve travels through the carpal tunnel, a narrow passage in the wrist formed by bones and the transverse carpal ligament. It supplies sensation to the palm side of the thumb, index finger, middle finger, and half of the ring finger. Additionally, it controls the thenar muscles, which enable thumb movement and facilitate opposition—the ability to touch the thumb to the fingertips, a function essential for gripping and dexterity.

Ulnar Nerve

The ulnar nerve passes through Guyon’s canal, a tunnel formed by the pisiform and hamate bones and their connecting ligament. This nerve supplies sensation to the little finger and half of the ring finger. It also innervates the intrinsic muscles of the hand, including the hypothenar muscles and the adductor pollicis, which draw the thumb toward the palm, contributing to fine motor control.

Nerve Compression Syndromes

The wrist’s intricate structure and constant movement make its nerves prone to compression and irritation. Repetitive wrist flexion and extension can lead to nerve entrapment syndromes, such as:

• Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS): Compression of the median nerve causing numbness, tingling, and weakness in the thumb, index, and middle fingers.

• Ulnar Nerve Compression (Guyon’s Canal Syndrome): Pressure on the ulnar nerve, leading to numbness, weakness, or muscle wasting in the little and ring fingers.

• Radial Tunnel Syndrome: Entrapment of the radial nerve, resulting in pain and weakness in the back of the hand and forearm.

Blood Supply to the Wrist and Hand

The blood vessels that supply the hand run alongside the nerves, ensuring adequate oxygen and nutrient delivery for function and healing.

Radial Artery

The radial artery runs along the thumb side of the wrist and is the primary site for checking the wrist pulse. It supplies blood to the thumb and lateral aspect of the hand, playing a crucial role in hand circulation.

Ulnar Artery

The ulnar artery travels through Guyon’s canal alongside the ulnar nerve. It supplies blood to the medial (little finger) side of the hand, ensuring oxygenation of the small intrinsic hand muscles.

Palmar and Dorsal Arterial Arches

The radial and ulnar arteries form two interconnected arches in the palm:

• Superficial Palmar Arch – Mainly supplied by the ulnar artery, it distributes blood to the fingers and palm.

• Deep Palmar Arch – Fed primarily by the radial artery, it supplies the bones and deep tissues of the hand.

Smaller dorsal arteries supply the back of the hand and fingers, ensuring balanced circulation.

Summary

The wrist is one of the most intricate anatomical structures in the body, allowing for precise movements, grip strength, and sensory perception. Its bones, ligaments, tendons, nerves, and blood vessels function together to enable daily activities ranging from fine motor tasks to heavy lifting. Given its constant use, the wrist is highly vulnerable to injuries and degenerative conditions, which can significantly impact hand function and quality of life. Understanding the anatomy and biomechanics of the wrist is essential for diagnosing and managing wrist-related disorders effectively.