As we age, our bones naturally become thinner, and their strength gradually diminishes. Osteoporosis is a condition where bones weaken significantly, making them prone to fractures. This condition can progress silently over many years, often without noticeable symptoms until a fracture occurs.

In cases of osteoporosis, fractures commonly happen in the spine. Known as vertebral compression fractures, these spinal injuries affect approximately 1.5 million individuals annually in the United States, nearly twice as frequently as other osteoporosis-related fractures, like those of the hip or wrist.

Although vertebral compression fractures can have various causes, osteoporosis often plays a crucial role. For many individuals, experiencing such a fracture may be the first indicator of a weakened skeletal structure due to osteoporosis.

Anatomy

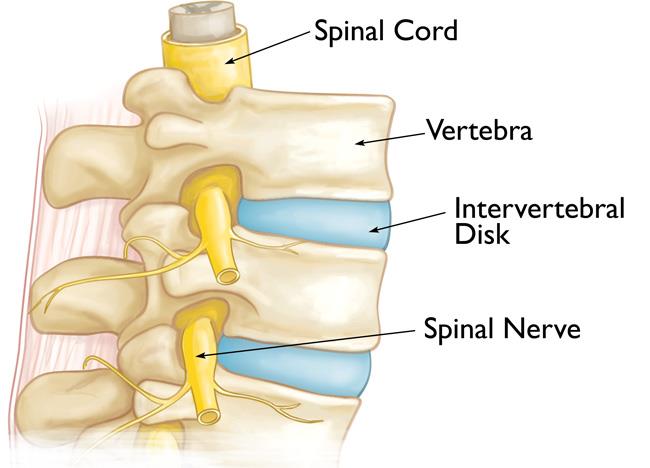

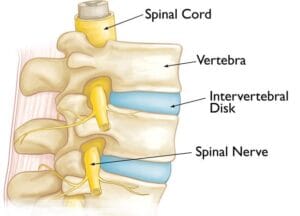

The spine consists of 24 stacked bones, known as vertebrae, which together form a protective canal for the spinal cord. In addition to the vertebrae, the spine includes:

- Spinal Cord and Nerves: These “electrical cables” run through the spinal canal, transmitting signals between the brain and muscles. Nerve roots extend outward from the spinal cord through openings in the vertebrae.

- Intervertebral Discs: Positioned between the vertebrae, these flexible, flat discs—each about half an inch thick—act as cushions, absorbing shock and protecting the vertebrae during activities like walking and running.

Causes

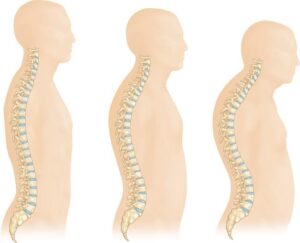

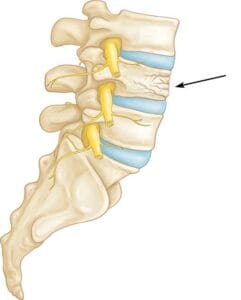

Osteoporosis is a natural part of aging, as bones gradually lose strength over time. When the vertebrae in the spine weaken, they may become thinner and flatter, often resulting in a loss of height and a rounded back or hunched posture in elderly individuals. These weakened vertebrae are particularly susceptible to fractures. A vertebral compression fracture occurs when excessive force is placed on a weakened vertebra, causing it to crack and reduce in height. While these fractures are commonly triggered by falls, people with osteoporosis can sustain them even from everyday movements like twisting, reaching, coughing, or sneezing.

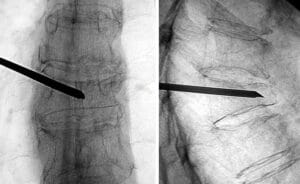

Symptoms Vertebral compression fractures often lead to localized back pain, usually centered around the fracture site. These fractures frequently occur around the waistline, as well as just above (mid-back) or below it (lower back). Movement, especially when changing positions, can intensify the pain, which typically eases with rest or lying down. Activities like coughing or sneezing may also increase discomfort. While it’s less common, the pain can sometimes radiate to other areas, such as the abdomen or legs. In severe cases, nerve pain may extend into the legs if the fracture impacts nearby nerves. Physical Examination During your consultation, the doctor will review your general health, medical history, and specific symptoms. They’ll conduct a physical exam to assess your spine’s alignment and posture while standing, as well as press on specific areas of your back to determine if the pain originates from a muscle or bone injury. To rule out damage to spinal nerve roots, a neurological exam will assess for any loss of sensation, reflex changes, or muscle weakness. Imaging Tests Imaging tests are crucial for evaluating the fracture and determining whether it is recent (acute) or older (chronic). When a vertebral compression fracture occurs, it’s essential to evaluate whether osteoporosis is present and determine its severity. X-rays can often reveal overall bone thinning in the spine, a condition known as osteopenia, which precedes osteoporosis. Osteopenia indicates reduced bone mass, which, if untreated, can progress to osteoporosis, making bones much more fragile and prone to fractures. To measure the degree of bone loss, a Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DEXA) scan is often used. This bone mineral density test helps the doctor assess fracture risk both in the spine and other bones. The DEXA results also guide treatment decisions, including whether medication is needed to address bone density loss. Timely osteoporosis treatment is critical; research shows that over 30% of individuals with a spinal compression fracture may experience another fracture within a year. Many patients with vertebral compression fractures recover within three months without specific fracture repair. Basic care, including short periods of rest, limited use of pain relief medications, and sometimes wearing a brace to restrict movement, often suffices. It’s important to note that while the bone heals, it doesn’t regain its original shape, but the healed bone becomes stable and less likely to collapse further. If osteoporosis is diagnosed, the risk for additional vertebral fractures—as well as fractures in the hip or wrist—increases. During this period, your doctor will discuss treatment options to improve bone density and reduce fracture risk. In cases where pain persists despite nonsurgical treatments, surgery may be an option. In the past, surgical solutions for vertebral compression fractures were extensive. However, minimally invasive vertebral augmentation techniques, such as kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty, are now available. Your surgeon will discuss which option may be better for you based on the fracture’s specifics.Doctor Examination

Bone Density Testing

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

Surgical Treatment

Surgical Outcomes