Arthritis affecting the hip joint can significantly hinder daily activities, with various types presenting unique challenges. The most prevalent form is osteoarthritis (OA), often referred to as degenerative arthritis. Unlike inflammatory arthritis, OA is non-inflammatory and primarily results from aging-related wear and tear or prior trauma. Typically affecting middle-aged individuals, OA manifests through progressive joint pain and stiffness but is not linked to immune system dysfunction.

Inflammatory arthritis, on the other hand, stems from an overactive immune system and is categorized as an autoimmune disorder. Unlike OA, this form of arthritis can affect individuals of all ages, frequently appearing in early adulthood. Beyond joint pain, inflammatory arthritis may involve multiple organ systems, such as the eyes, lungs, heart, gastrointestinal tract, and skin. Common types of inflammatory arthritis impacting the hip joint include rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis. Less common variants include systemic lupus erythematosus, juvenile inflammatory arthritis (JIA), and immune checkpoint inhibitor-induced arthritis from chemotherapy.

Additionally, certain inflammatory arthritis types are not autoimmune but still cause hip joint symptoms. Examples include gout (uric acid crystal accumulation), pseudogout (calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition), septic arthritis (bacterial or viral infection), and Lyme arthritis (associated with Lyme disease).

While there is no definitive cure for inflammatory arthritis, significant progress in treatment options—especially new medications—has improved outcomes. Early diagnosis and proactive treatment are crucial for preserving joint function and mobility, preventing severe joint damage over time.

Anatomy

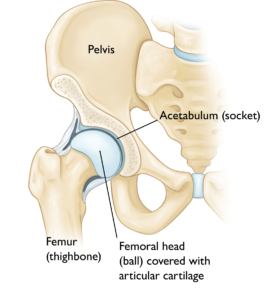

The hip joint is a classic example of a ball-and-socket joint, designed for stability and a wide range of motion. The socket is formed by the acetabulum, a part of the pelvic bone, while the ball is the femoral head, located at the upper end of the femur (thighbone).

A smooth, slippery tissue known as articular cartilage coats the surfaces of the ball and socket. This cartilage minimizes friction, allowing the bones to glide effortlessly during movement. Additionally, the joint is lined by a thin membrane called the synovium. In a healthy hip, the synovium produces a small quantity of fluid that lubricates the cartilage and facilitates smooth movement.

Common Types of Inflammatory Arthritis in the Hip

Description

Inflammatory arthritis encompasses several conditions that can significantly impact the hip joint, causing pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility. Below are the most common types of inflammatory arthritis affecting the hip:

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune condition where the synovium thickens, swells, and releases chemicals that degrade the articular cartilage covering the joint. This process leads to pain, stiffness, and joint damage. Rheumatoid arthritis commonly affects the same joint on both sides of the body, often involving both hips.

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis primarily targets the spine and large joints, including the hips. It causes inflammation that leads to stiffness and pain. Over time, it may result in the erosion of the sacroiliac joint and fusion of the spine, a condition often referred to as “bamboo spine.”

Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is a form of arthritis seen in individuals with psoriasis, a skin condition marked by red, scaly patches. This type of arthritis is characterized by:

- Red, swollen, and warm joints.

- Sausage-like swelling in the fingers and toes.

- Nail changes, such as pitting.

- Pain localized to the tailbone (coccyx) in some cases.

- Rephrased Cause Section:Inflammatory arthritis arises when the body’s immune system fails to regulate itself, mistakenly attacking its own tissues. This immune dysfunction leads to the infiltration of immune cells into areas where inflammation is unnecessary, triggering the release of chemicals that damage affected tissues.While the exact cause of inflammatory arthritis remains unclear, research suggests that genetic factors contribute to the development of certain types of the condition.

Symptoms

Inflammatory arthritis can cause a range of systemic symptoms, including fever, fatigue, and loss of appetite. When it affects the hip joint, individuals may experience pain, stiffness, and additional localized symptoms, such as:

- A dull, persistent ache in the groin, outer thigh, knee, or buttocks.

- Reduced range of motion in the hip.

- Pain that worsens in the morning or after periods of inactivity, improving slightly with movement.

- Severe joint pain that may result in limping or difficulty walking.

These symptoms can vary in intensity but often interfere with daily activities and overall mobility.

Medical Evaluation and Diagnosis of Inflammatory Hip Arthritis

Doctor Examination

If inflammatory arthritis of the hip is suspected, it is essential to consult a rheumatologist—a specialist in diagnosing and treating autoimmune diseases. Without timely intervention, long-standing inflammatory arthritis or cases resistant to medical treatment can result in severe joint damage, often necessitating joint replacement surgery.

During the initial consultation, your doctor will review your medical history and discuss your symptoms. This will be followed by a physical examination and diagnostic tests to confirm the diagnosis and assess the severity of the condition.

Physical Examination

As part of the physical examination, your doctor will assess the range of motion in your hip. If certain movements trigger pain or are restricted, it could indicate inflammatory arthritis. Additionally, the doctor will observe your gait (the way you walk) to identify any limping or movement difficulties caused by hip stiffness.

X-ray

X-rays are commonly used to evaluate the condition of the hip joint. These imaging tests provide detailed views of dense structures, such as bones. In cases of inflammatory arthritis, X-rays can reveal key indicators such as bone thinning, erosion, loss of joint space, or excess fluid accumulation in the joint. This information helps in determining the extent of joint damage and planning an appropriate treatment strategy.

Blood Tests

Blood tests play a vital role in diagnosing inflammatory arthritis. Markers such as the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are commonly used to detect inflammation in the body. Additionally, specific antibodies like rheumatoid factor (RF), antinuclear antibodies (ANA), and anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPA) provide valuable insights into autoimmune processes that contribute to the condition.

Treatment

While there is no definitive cure for inflammatory arthritis, a variety of treatment options can effectively manage symptoms and prevent joint damage. Treatment typically involves a multidisciplinary team, including rheumatologists, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, rehabilitation specialists, and orthopedic surgeons, to provide comprehensive care.

Nonsurgical Treatment

The choice of treatment depends on the specific type and progression of the inflammatory condition. Advances in medical therapies have transformed outcomes, often allowing individuals to achieve remission when treated early.

- Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Medications like ibuprofen and naproxen can alleviate pain and reduce inflammation. These are available over the counter or by prescription.

- Corticosteroids: Powerful anti-inflammatory drugs like prednisone can suppress the immune response. They can be administered orally or through injections.

- Injections for Hip Pain: Corticosteroid, hyaluronic acid, or platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections can be effective in controlling hip pain and inflammation.

- Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs (DMARDs): Medications such as methotrexate target the immune system to slow disease progression.

- Biologic Medications: These genetically engineered proteins specifically block parts of the immune system responsible for inflammation. Biologics are highly effective in managing conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis.

- Physical Therapy: Tailored exercises can improve hip range of motion and strengthen supporting muscles. Activities like swimming are particularly beneficial for individuals with ankylosing spondylitis, as they minimize spinal stiffness.

- Assistive Devices: Canes, walkers, and other tools can help with mobility and reduce strain on the hip joint.

Surgical Treatment

If nonsurgical methods do not provide sufficient relief, surgical intervention may be recommended. The choice of surgery depends on factors such as age, hip joint condition, type of arthritis, and disease progression.

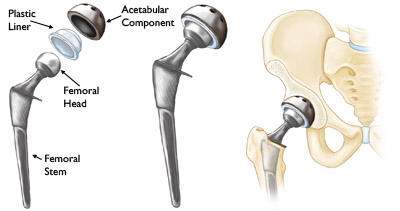

- Total Hip Replacement: This procedure involves removing the damaged cartilage and bone, replacing them with metal or plastic components to restore hip function. It is commonly performed for conditions like rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis to reduce pain and improve mobility.

- Synovectomy: This surgery removes all or part of the inflamed joint lining (synovium). It is typically used in early-stage inflammatory arthritis before significant cartilage damage occurs.

Your doctor will explain the surgical options, the reasons for their recommendation, and the expected outcomes. Be sure to ask questions and understand the benefits and risks involved.

Surgical Complications and Recovery

Although rare, surgical complications can occur. Common risks include infection, excessive bleeding, blood clots, damage to blood vessels or nerves, dislocation of the new joint (in total hip replacement), and differences in leg length. Your surgeon will take measures to minimize these risks and discuss them thoroughly with you.

Recovery time varies depending on your overall health and the procedure performed. Walking aids like canes or crutches may be necessary initially, and physical therapy is often recommended to restore strength and mobility in the hip.