Collateral ligament injuries, such as sprains or tears, are among the most common knee injuries experienced by athletes. These essential ligaments connect the thighbone (femur) to the bones of the lower leg, providing stability and support to the knee joint. The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is located on the inner side of the knee, while the lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is on the outer side. Athletes engaged in high-impact sports, such as football or soccer, which involve frequent contact and sudden movements, face a higher risk of damaging these ligaments.

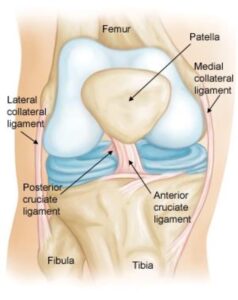

Anatomy of the Knee Joint

The knee joint is formed by the connection of three key bones: the femur (thighbone), tibia (shinbone), and patella (kneecap). The patella is positioned in front of the joint, acting as a protective shield.

Ligaments, which are strong connective tissues, link bones together and play a crucial role in stabilizing the knee. There are four main ligaments in the knee that function like durable ropes to maintain its stability:

- Collateral Ligaments:

Located on the sides of the knee, these ligaments help control side-to-side movements and protect the knee against abnormal motion.- The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is situated on the inner side of the knee and connects the femur to the tibia.

- The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) lies on the outer side and links the femur to the fibula, the smaller bone in the lower leg.

- Cruciate Ligaments:

Found within the knee joint, these ligaments cross each other in an X-shaped formation. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is located in the front, while the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is positioned at the back. Together, they manage the forward and backward movement of the knee.

Normal knee anatomy. The knee is made up of four main things: bones, cartilage, ligaments, and tendons.

Description of Knee Injuries

The knee joint depends heavily on its ligaments and surrounding muscles for stability, making it prone to injuries. Sudden impacts, such as direct blows to the knee, or forceful muscle contractions, like abruptly changing direction during running, can damage these ligaments.

Ligament injuries, commonly referred to as sprains, are categorized based on their severity:

- Grade 1 Sprains:

In this mild form of injury, the ligament is slightly stretched but retains its ability to stabilize the knee joint. - Grade 2 Sprains:

A moderate injury where the ligament is stretched to the point of becoming loose. This condition is often called a partial ligament tear. - Grade 3 Sprains:

A severe injury involving a complete tear of the ligament. The ligament is either split into two or completely detached from the bone, resulting in an unstable knee joint.

Among these, the MCL is injured more frequently than the LCL. Due to the intricate structure on the outer side of the knee, an LCL injury is often accompanied by damage to other components of the joint.

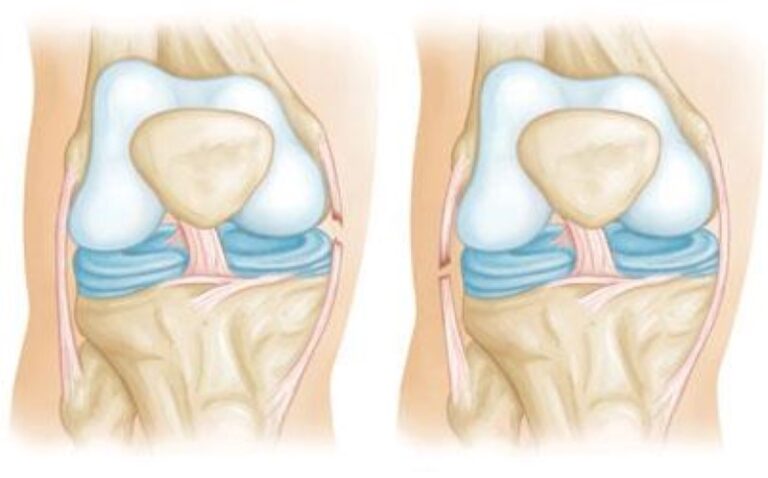

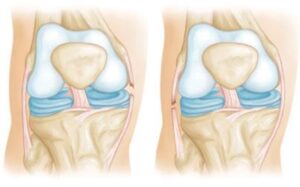

Complete tears of the MCL (left) and LCL (right).

Complete tears of the MCL (left) and LCL (right).

Causes of Collateral Ligament Injuries

Collateral ligament injuries often result from a force that pushes the knee sideways, with contact injuries being the most common cause.

- Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) Injuries:

These injuries typically occur due to a direct blow to the outer side of the knee, forcing it inward toward the opposite knee. - Lateral Collateral Ligament (LCL) Injuries:

Blows to the inner side of the knee that push it outward can cause damage to the LCL.

Symptoms of Collateral Ligament Injuries

Signs of a collateral ligament injury may include:

- Localized Pain: Pain on the inner side of the knee indicates an MCL injury, while pain on the outer side suggests an LCL injury.

- Swelling: Swelling is often present around the injured area.

- Instability: A sensation that the knee is unstable or “giving way” may occur.

Diagnosis of Collateral Ligament Injuries

Physical Examination and Medical History

Your doctor will begin by discussing your symptoms and reviewing your medical history. A thorough physical examination will compare the injured knee with the uninjured one, often providing sufficient information to diagnose ligament injuries.

Imaging Tests

To confirm the diagnosis, the following tests may be performed:

- X-rays: While X-rays cannot show ligament damage, they can reveal if the ligament injury caused a piece of bone to break off (avulsion).

- MRI Scans: Magnetic resonance imaging produces detailed images of soft tissues, making it effective for visualizing the collateral ligaments.

Treatment Options for Collateral Ligament Injuries

Nonsurgical Treatments

- Ice Therapy: Applying crushed ice to the injured area for 15–20 minutes at a time, with at least an hour between sessions, helps reduce swelling. Avoid placing chemical cold packs directly on the skin, as they are less effective and may cause skin irritation.

- Bracing and Activity Modification: A hinged brace may be recommended to prevent further stress on the injured ligament. Crutches may be provided to avoid weight-bearing on the affected leg.

- Physical Therapy: Strengthening and flexibility exercises help restore knee function and improve the strength of surrounding muscles.

Surgical Treatments

Surgery is generally reserved for severe cases, such as when the ligament is torn in a way that prevents natural healing or when the injury involves other structures in the knee. Surgical repair techniques will be tailored to the specific injury, and your surgeon will guide you through the best option for recovery.

Returning to Sports Activities

Rehabilitation focuses on restoring range of motion, eliminating limping, and gradually reintroducing physical activity.

- Functional Progression: This involves a step-by-step return to sports, starting with light jogging, advancing to sprints, and eventually resuming full activity, such as running and kicking in soccer.

- Protective Measures: Depending on the severity of the injury, your doctor may recommend using a knee brace during sports to provide additional support.

By following the recommended treatment and rehabilitation plan, athletes can recover fully and minimize the risk of re-injury.