Cause

In adults, Baker’s cysts often arise from conditions or injuries that lead to swelling and inflammation within the knee joint. Common triggers include:

- Osteoarthritis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Meniscus tears

- Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tears

- Other conditions that damage the knee’s internal tissues

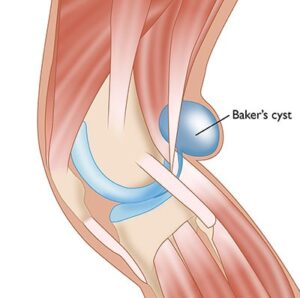

When inflammation occurs, the knee responds by producing excessive synovial fluid. This surplus fluid can move to the back of the knee and collect within the popliteal bursa, causing it to swell and form a Baker’s cyst.

In younger individuals, Baker’s cysts are often idiopathic, meaning they develop without a known underlying cause.

A cyst forms when excess synovial fluid travels to the popliteal bursa at the back of the knee.

A cyst forms when excess synovial fluid travels to the popliteal bursa at the back of the knee.

Symptoms

Many Baker’s cysts are asymptomatic, often discovered incidentally during a routine physical examination or imaging tests like an MRI performed for unrelated reasons. However, when symptoms are present, they may include:

- A noticeable lump or sensation of fullness behind the knee

- Pain in the knee

- Stiffness or a feeling of tightness at the back of the knee

- Swelling that may extend to the knee and lower leg

In cases where the cyst grows significantly in size, it may compress nearby structures, potentially interfering with blood flow in the leg veins. This can lead to symptoms such as pain, swelling, weakness, or numbness due to nerve compression. In rare instances, a Baker’s cyst may even rupture, releasing fluid into surrounding tissues.

It’s important to note that the symptoms of a Baker’s cyst can sometimes mimic those of more serious conditions like a blood clot or deep vein thrombosis (DVT). If you experience increasing pain and swelling in your calf, seek medical attention promptly to rule out the possibility of a blood clot.

Doctor Examination

Medical History and Physical Examination

To accurately diagnose a Baker’s cyst, your doctor will begin by reviewing your complete medical history and asking about your symptoms. This includes inquiries about any previous knee injuries that may contribute to the condition.

A thorough physical examination of the affected knee will follow, with comparisons to the unaffected knee. During the evaluation, your doctor will check for:

- Swelling around the joint

- Joint instability

- Clicking or popping sounds when bending the knee

- Stiffness or restricted range of motion

The doctor will also palpate the area behind your knee to assess the cyst. Typically, a Baker’s cyst feels firm when the knee is fully extended and softer when the knee is bent.

Imaging Tests

Imaging tests are often used to confirm the diagnosis and gather additional details about the knee joint’s condition.

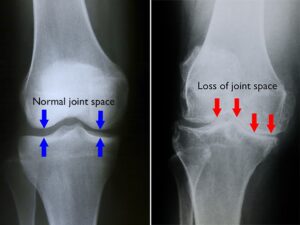

- X-rays: While X-rays do not show the cyst itself, they can help identify other underlying issues, such as joint space narrowing or signs of arthritis, which may be contributing to the development of the cyst.

(Left) In this x-ray of a normal knee, the space between the bones indicates healthy cartilage. (Right) This x-ray of an arthritic knee shows severe loss of joint space.

(Left) In this x-ray of a normal knee, the space between the bones indicates healthy cartilage. (Right) This x-ray of an arthritic knee shows severe loss of joint space.

- Ultrasound: Ultrasound imaging uses sound waves to produce detailed images of the structures inside your body. This non-invasive test allows your doctor to examine the lump behind your knee more closely, helping to determine whether the cyst is fluid-filled or solid.

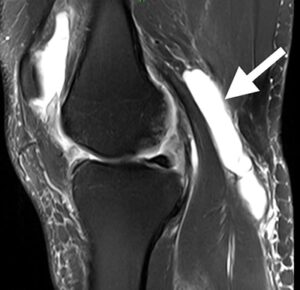

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI scans provide highly detailed images of the soft tissues within the knee. Your doctor may recommend an MRI to gain more insight into the cyst and to identify any underlying issues, such as a meniscus tear or other joint abnormalities, that could be contributing to your symptoms.

This MRI scan shows an area of fluid behind the knee, the characteristic location of a Baker’s cyst.

This MRI scan shows an area of fluid behind the knee, the characteristic location of a Baker’s cyst.

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

In most cases, Baker’s cysts resolve on their own without requiring treatment. For cysts that persist, nonsurgical options are typically recommended as the first line of treatment and may include:

- Observation: Your doctor may choose to monitor the cyst over time to ensure it does not grow larger or cause discomfort.

- Activity Modification: Reducing activities that place stress on the knee, such as running or aerobics, can help alleviate symptoms and prevent further irritation.

- Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Medications like ibuprofen or naproxen can help decrease pain and reduce swelling in the affected area.

- Steroid Injections: A corticosteroid injection into the knee joint may be used to minimize inflammation and relieve symptoms.

- Aspiration: This procedure involves numbing the area around the cyst and using a needle to drain excess fluid from the joint. Ultrasound guidance is often employed to ensure accurate needle placement.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is rarely required to address a Baker’s cyst. However, it may be considered if symptoms persist despite nonsurgical treatments or if the cyst recurs frequently after aspiration.

- Arthroscopy: During this minimally invasive procedure, the doctor makes small incisions and uses an arthroscope—a tiny camera—to visualize the inside of the knee joint. Guided by the camera, specialized surgical tools are used to address underlying issues such as meniscus tears, which may be contributing to the formation of the cyst.

Photo shows a camera and instruments inserted through portals in the knee.

Photo shows a camera and instruments inserted through portals in the knee.

Excision

For larger Baker’s cysts or those causing complications such as nerve compression or vascular issues, your doctor may recommend an open surgical procedure to completely remove the cyst.

Recovery

Following recovery guidelines is crucial to minimize the risk of a Baker’s cyst recurring.

- Early Movement: If your cyst has been aspirated or you’ve undergone arthroscopic surgery, walking is usually permitted soon after the procedure. However, you should refrain from engaging in strenuous activities during the recovery period.

- Bracing: Your doctor may advise wearing a knee brace for several weeks after surgery to keep the knee stable and promote healing.

- Physical Therapy: Targeted exercises can help restore the knee’s range of motion and strengthen the surrounding muscles, supporting a quicker recovery.

The recovery timeline varies based on individual circumstances and whether underlying knee issues were treated during the procedure. Most patients can expect to resume normal activities within 4 to 6 weeks following surgery.

A Baker’s cyst (arrow) can cause a sense of fullness behind your knee, especially when you straighten your leg.

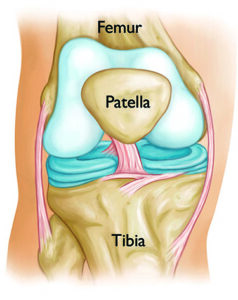

A Baker’s cyst (arrow) can cause a sense of fullness behind your knee, especially when you straighten your leg. The bones that make up the knee joint.

The bones that make up the knee joint.

This MRI scan shows an area of fluid behind the knee, the characteristic location of a Baker’s cyst.

This MRI scan shows an area of fluid behind the knee, the characteristic location of a Baker’s cyst.