Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are among the most frequent knee injuries, often involving a sprain or tear. These injuries are particularly common among athletes engaged in high-intensity sports such as soccer, basketball, and football, where sudden stops and directional changes put the knee at risk. If you have sustained an ACL injury, surgical intervention may be necessary to restore full knee functionality. However, the need for surgery depends on various factors, including the extent of the injury and your activity level. For a comprehensive discussion on treatment options, refer to the article, “ACL Injury: Does It Require Surgery?” which serves as a valuable companion to this guide.

Anatomy of the Knee Joint

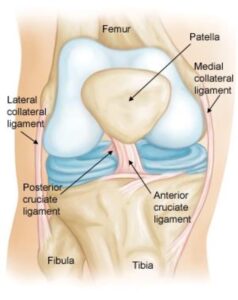

The knee joint is a complex structure where three bones converge: the femur (thighbone), tibia (shinbone), and patella (kneecap). Positioned at the front of the joint, the kneecap offers essential protection to the knee.

Ligaments play a crucial role in connecting bones and ensuring joint stability. In the knee, four primary ligaments function like robust ropes, holding the bones together and maintaining the joint’s stability.

Collateral Ligaments: Supporting Side-to-Side Movement

The collateral ligaments are located on either side of the knee. The medial collateral ligament (MCL), positioned on the inner side, and the lateral collateral ligament (LCL), located on the outer side, manage the knee’s side-to-side motion. These ligaments also provide support against excessive sideways movements, ensuring the knee remains stable.

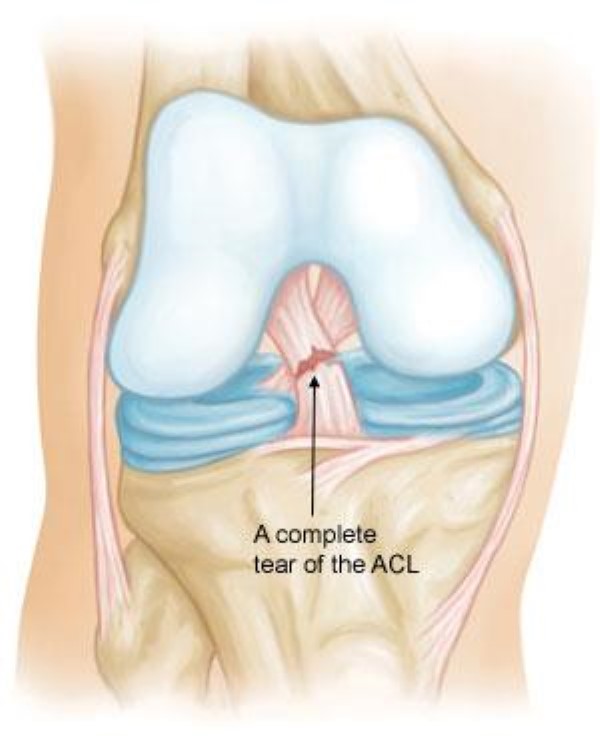

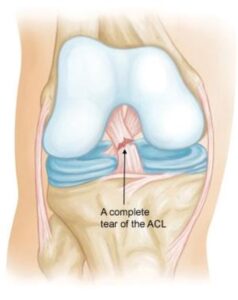

Cruciate Ligaments: Controlling Forward and Backward Motion

Situated within the knee joint, the cruciate ligaments form an X-shape by crossing over each other. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is positioned at the front, while the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is at the back. Together, they regulate the forward and backward movement of the knee.

The ACL runs diagonally through the center of the knee, preventing the tibia from sliding too far forward relative to the femur and ensuring rotational stability. The PCL, which is stronger and less frequently injured than the ACL, prevents excessive backward movement of the tibia, safeguarding the knee’s structural integrity.

Normal knee anatomy. The knee is made up of four main things: bones, cartilage, ligaments, and tendons.

Normal knee anatomy. The knee is made up of four main things: bones, cartilage, ligaments, and tendons.