Synovial chondromatosis, also known as synovial osteochondromatosis, is a rare, non-cancerous (benign) disorder that affects the synovium, the thin layer of tissue lining the joints. While this condition most commonly develops in the knee joint, it can also impact other joints throughout the body, such as the hip, elbow, and shoulder.

Although synovial chondromatosis is benign, it can lead to significant joint damage if left untreated, eventually progressing to osteoarthritis. Early diagnosis and intervention are essential to alleviate symptoms, prevent joint damage, and maintain joint health.

Anatomy of Joints and Synovium

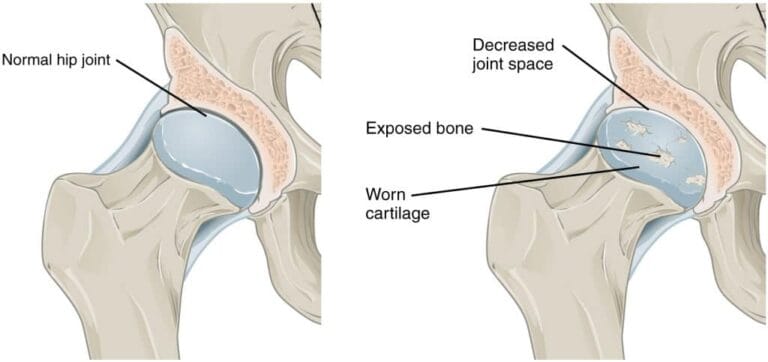

A joint is where two or more bones connect, as seen in the knee, shoulder, and ankle joints. In healthy joints, the bones are covered by articular cartilage, a smooth tissue that helps the bones glide effortlessly. The joint is protected by a capsule of thick tissue, and the inner layer of this capsule, the synovium, produces synovial fluid—the lubricant that keeps the joint moving smoothly.

The knee joint is the most commonly affected location for synovial chondromatosis. Although not visible in standard imaging, the condition starts in the thin synovial membrane that lines the joint. This is where abnormal growth occurs, leading to the development of the characteristic cartilage nodules

The knee joint is the most commonly affected location for synovial chondromatosis. Although not visible in standard imaging, the condition starts in the thin synovial membrane that lines the joint. This is where abnormal growth occurs, leading to the development of the characteristic cartilage nodules

Description of Synovial Chondromatosis

In synovial chondromatosis, the synovium undergoes abnormal growth and produces cartilage nodules. These nodules can sometimes detach from the synovium and become loose bodies within the joint.

The loose bodies can vary in size, from a few millimeters (the size of a small pill) to a few centimeters (similar to a marble). These loose bodies are nourished by the synovial fluid, and may grow, calcify (harden), or even ossify (transform into bone). As they roll around the joint space, they can damage the articular cartilage, which can lead to osteoarthritis.

In more severe cases, the loose bodies can occupy the entire joint space or invade surrounding tissues, leading to further joint complications.

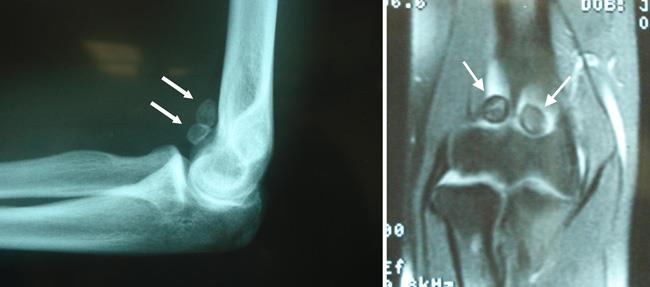

In these X-rays of the elbow joint (left) and ankle joint (right), the loose bodies associated with synovial chondromatosis are clearly visible.

In these X-rays of the elbow joint (left) and ankle joint (right), the loose bodies associated with synovial chondromatosis are clearly visible.

(Left) Reproduced from Johnson TR, Steinbach LS (eds.): Essentials of Musculoskeletal Imaging. Rosemont, IL, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2004, p. 297.

Commonly Affected Joints and Demographics

Synovial chondromatosis most often affects the knee joint, though it can also appear in the hip, elbow, and shoulder joints. Usually, the condition affects just one joint at a time. It typically occurs in individuals between the ages of 30 and 50, with men being twice as likely as women to develop this condition.

Cause of Synovial Chondromatosis

The exact cause of synovial chondromatosis remains unknown, and it occurs spontaneously. It is not hereditary and does not run in families.

Symptoms of Synovial Chondromatosis

Symptoms of synovial chondromatosis often mimic those of osteoarthritis, and include:

- Joint pain

- Joint swelling

- Limited range of motion

Other symptoms may include:

- Fluid accumulation in the joint

- Tenderness in the joint area

- A creaking, grinding, or popping sound during movement (known as crepitus)

In joints close to the skin, such as the knee, ankle, and elbow, the cartilage nodules may even be felt.

Doctor Examination and Diagnosis

Early diagnosis and treatment of synovial chondromatosis are key to preventing joint damage and the progression of **osteoarthosteoarthritis.

Physical Examination

During the examination, your doctor will discuss your

- Swelling

- Tenderness

- Limited range of motion

- Grinding or creaking noises during movement, which may indicate bone-on-bone friction

Diagnostic Tests

Your doctor will likely order imaging tests to confirm the diagnosis of synovial chondromatosis and differentiate it from **osteoosteoarthritis.

- X-rays: X-rays provide clear images ocalcified or ossified loose bodies are typically visible

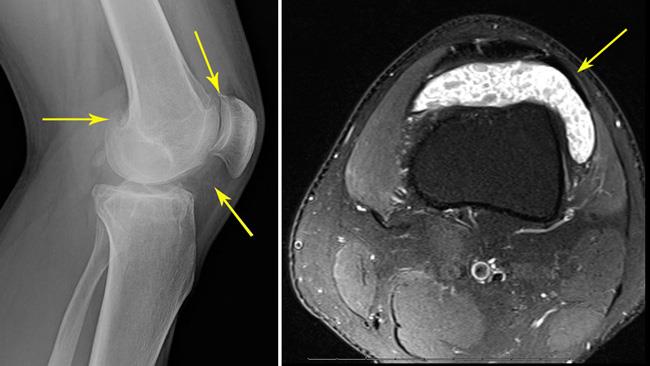

(Left) In this X-ray of a knee joint, the small loose bodies are barely visible (indicated by arrows). (Right) In this MRI scan, a cross-sectional image of the same knee shows the loose bodies more clearly (arrow).

(Left) In this X-ray of a knee joint, the small loose bodies are barely visible (indicated by arrows). (Right) In this MRI scan, a cross-sectional image of the same knee shows the loose bodies more clearly (arrow).

(Left) X-ray of an elbow joint reveals two large ossified loose bodies (indicated by arrows). (Right) The MRI scan provides a cross-sectional image of the same elbow.

(Left) X-ray of an elbow joint reveals two large ossified loose bodies (indicated by arrows). (Right) The MRI scan provides a cross-sectional image of the same elbow.

Reproduced from Ahmad CS, Vitale MA: Elbow arthroscopy: setup, portal placement, and simple procedures. Instructional Course Lectures, Vol. 60. Rosemont, IL, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2011, pp. 171-180.

- Other Imaging Tests: If X-rays do not reveal the loose bodies, your doctor may order amagnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or **computed tomogracomputed tomography (CT) scan. These scans provide a more detailed view of the joint aloose bodies, as well as other conditions like **ffluid accumulation or **joint space narrowijoint space narrowing (a sign of osteoarthritis).

Treatment of Synovial

Nonsurgical Treatment

Observation: In mild cases, observation may be recommended. Your doctor wosteoporosisprogression or worsening symptoms durin

Surgical Treatment

For most patients, surgery is the best option to remove the loose cartilage bodies. In some cases, the synovisynovectomy.

The type of surgery

- The number of loose bodies

- The size of the loose

- The condition of the *synovium

During an open surgical procedure, the surgeon makes one or two incisions to remove a large number of loose bodies from the knee joint.

During an open surgical procedure, the surgeon makes one or two incisions to remove a large number of loose bodies from the knee joint.

Open Surgery vs. Arthroscopy

In a traditional open surgery, the surgeon makes one or two lararthroscopic procedure, smaller incisions aBoth

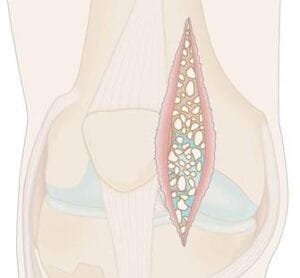

Calcified loose bodies removed from the knee joint of a patient with synovial chondromatosis.

Calcified loose bodies removed from the knee joint of a patient with synovial chondromatosis.

Recovery After Surgery for Synovial Chondromatosis

Recovery time depends on the type of surgery performed and the affected joint. Your doctor will provide you with personalized instructions to support your rehabilitation and help you return to your daily activities safely.

Even after surgery, synovial chondromatosis may recur in up to 20% of patients. To monitor for recurrence, your doctor will schedule follow-up visits and assess the joint for signs of osteoarthritis progression. The degree of joint damage prior to surgery will influence your risk of developing osteoarthritis.