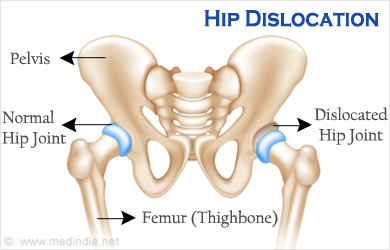

A traumatic hip dislocation occurs when the head of the femur (thighbone) is forcibly displaced from its socket in the hip bone (pelvis). This injury typically requires a substantial force, such as from a car accident or a fall from a significant height, and is often accompanied by other injuries, such as fractures.

Anatomy of the Hip

The hip joint is a ball-and-socket joint, consisting of:

- The acetabulum, a part of the pelvis that forms the socket.

- The femoral head, the ball at the upper end of the femur.

Articular cartilage covers both the ball and the socket, allowing smooth movement. The acetabulum is surrounded by fibrocartilage called the labrum, providing stability. Ligaments also contribute to the joint’s stability.

Description of Hip Dislocation In a hip dislocation, the femoral head is displaced either backward (posterior dislocation) or forward (anterior dislocation).

- Posterior Dislocation: Occurs in approximately 90% of cases. The femur is pushed backward, leaving the lower leg in a fixed position with the knee and foot rotated inward.

- Anterior Dislocation: The femur slips forward, causing the knee and foot to rotate outward.

Such dislocations often damage the surrounding ligaments, labrum, muscles, and other soft tissues. Nerve injuries are also possible.

Causes Common causes of traumatic hip dislocations include:

- Motor vehicle accidents, particularly when the knee hits the dashboard.

- Falls from significant heights.

- Industrial accidents.

- Collisions in sports like football or rugby.

These dislocations are often associated with other injuries, such as fractures in the pelvis and legs, and injuries to the back, abdomen, and head. A common accompanying injury is a posterior wall acetabular fracture-dislocation.

Symptoms A hip dislocation is extremely painful. Patients cannot move the leg and may lose sensation in the foot or ankle if nerves are damaged.

Diagnosis and Examination Hip dislocation is a medical emergency. Immediate medical attention is required. Do not attempt to move the injured person; keep them warm with blankets.

An orthopaedic surgeon can often diagnose a dislocation by examining the leg’s position. Imaging tests like X-rays and CT scans confirm the diagnosis and check for additional injuries.

Treatment Reduction Procedures If no other injuries are present, an orthopaedic surgeon will perform a reduction procedure, manipulating the bones back into their proper position under anesthesia or sedation. Sometimes, surgery is required to remove loose tissues or fragments blocking the femur from returning to the socket.

Nonsurgical Treatment If the hip joint is stable and there are no fractures, nonsurgical treatment may be suitable. This includes avoiding weight-bearing on the injured leg for 6 to 10 weeks and steering clear of certain positions.

Surgical Treatment Surgery is necessary if there are associated fractures or if the hip remains unstable after reduction. The goal is to restore stability and align the cartilage surfaces. This surgery often involves a large incision and may require a blood transfusion.

Complications Long-term consequences of hip dislocation can include:

- Nerve Injury: The sciatic nerve is commonly affected, causing weakness in the lower leg.

- Osteonecrosis: Loss of blood supply can lead to bone death and arthritis.

- Arthritis: Damage to the cartilage increases arthritis risk, potentially necessitating hip replacement surgery.

Recovery Healing from a hip dislocation can take 2 to 3 months, longer if fractures are present. Physical therapy is crucial for recovery, with patients often starting to walk with crutches shortly after the injury. Walking aids help regain mobility during the rehabilitation process.

In summary, traumatic hip dislocations are serious injuries requiring immediate medical attention and a comprehensive treatment plan to ensure proper healing and recovery.