Introduction:

Guyon’s Canal Syndrome refers to the compression of the ulnar nerve as it travels through a passage in the wrist known as Guyon’s canal. While this condition is similar to carpal tunnel syndrome, it affects a different nerve entirely. In some cases, both conditions can occur simultaneously in the same hand.

This guide provides insights into:

- The development of Guyon’s canal syndrome

- How the condition is diagnosed

- Available treatment options

Anatomy:

Where Is the Ulnar Nerve and What Is Its Function?

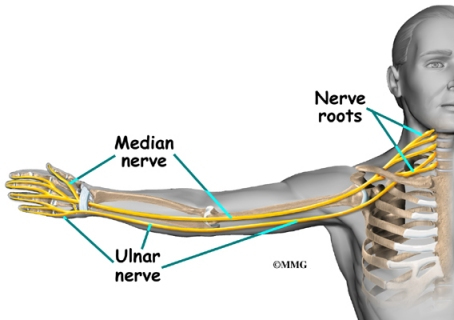

The ulnar nerve originates at the side of the neck, where individual nerve roots exit the spinal column through small openings between the vertebrae. These roots merge to form three main nerves that travel down the arm to the hand, one of which is the ulnar nerve.

After leaving the neck, the ulnar nerve passes through the armpit, continues down the arm, and reaches the hand and fingers. As it crosses the wrist, the ulnar nerve and the ulnar artery pass through a tunnel called Guyon’s canal. This canal is formed by two bones, the pisiform and hamate, connected by a ligament. Beyond this tunnel, the ulnar nerve branches out to provide sensation to the little finger and half of the ring finger. It also controls the small muscles in the palm and the muscle responsible for moving the thumb toward the palm.

One side of Guyon’s canal is formed by the hamate bone, which has a small hook-shaped projection called the hook of hamate. This structure provides an attachment point for several wrist ligaments. However, if the hook of hamate breaks, it can press against the ulnar nerve within the canal, potentially leading to compression.

Causes :

What Causes Guyon’s Canal Syndrome?

Guyon’s canal syndrome can result from various factors. Overuse of the wrist through activities involving heavy gripping, twisting, or repetitive wrist and hand motions is a common cause. Working with the wrist bent downward and outward can also compress the nerve within Guyon’s canal.

Constant pressure on the palm is another contributing factor, often seen in cyclists and weightlifters due to prolonged gripping. Similar pressure can occur from operating tools like a jackhammer or using crutches.

Irritation or compression of the ulnar nerve leads to symptoms of Guyon’s canal syndrome. Swelling from a traumatic wrist injury can increase pressure on the nerve. Additionally, arthritis in the wrist bones and joints can irritate or compress the ulnar nerve over time. In rare cases, damage to the ulnar artery—located next to the nerve—can result in a blood clot. This clot mimics the symptoms of Guyon’s canal syndrome, likely due to reduced blood supply to the nerve.

A fractured hamate bone is another potential cause. This fracture can pinch the ulnar nerve within Guyon’s canal. Such injuries may occur when a golfer strikes the ground instead of the ball or when a baseball player is batting.

Symptoms:

What Are the Symptoms of Guyon’s Canal Syndrome?

The initial symptoms of Guyon’s canal syndrome often include a tingling or “pins and needles” sensation in the ring and little fingers, typically noticed early in the morning upon waking. Over time, this can progress to a burning pain in the wrist and hand, accompanied by reduced sensation in the ring and little fingers. As the condition worsens, weakness may develop in the hand muscles controlled by the ulnar nerve. This weakness can affect the small muscles in the palm and the muscle responsible for pulling the thumb into the palm, making it challenging to spread the fingers or pinch using the thumb.

Although Guyon’s canal syndrome is much less common than carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), both conditions can sometimes occur simultaneously. However, the numbness caused by each syndrome affects different areas of the hand. In CTS, compression of the median nerve results in pain and numbness in the thumb, index finger, middle finger, and half of the ring finger. In contrast, ulnar nerve compression in Guyon’s canal syndrome primarily causes numbness in the pinky and half of the ring finger.

Diagnosis:

How Is Guyon’s Canal Syndrome Diagnosed?

Diagnosing Guyon’s canal syndrome begins with a thorough medical history and physical examination. Since the ulnar nerve can be compressed at various points, your doctor will perform specific tests to identify the exact location of the issue. If the physical exam does not clearly indicate where the nerve is being compressed, additional diagnostic tests, such as electrical studies, may be recommended.

One common test is nerve conduction velocity (NCV), which measures how quickly nerve impulses travel along the ulnar nerve. This test helps pinpoint the area of compression. In some cases, an electromyogram (EMG) is also performed. The EMG evaluates the function of the forearm muscles controlled by the ulnar nerve. If these muscles are not functioning properly, it indicates potential issues with the nerve supplying them—similar to diagnosing faulty wiring in a lamp when replacing the bulb doesn’t resolve the issue.

If symptoms began following a traumatic wrist injury, X-rays might be required to check for fractures or dislocations in the wrist bones that could be affecting the ulnar nerve.

Treatment:

What Are the Treatment Options for Guyon’s Canal Syndrome?

Nonsurgical Treatment

To alleviate symptoms, it’s essential to modify or avoid activities that contribute to the condition. This includes reducing repetitive hand movements, heavy gripping, resting the palm on hard surfaces, and working with the wrist bent down and outward.

A wrist brace can help manage symptoms, especially during the early stages of Guyon’s canal syndrome. It keeps the wrist in a neutral position, preventing excessive bending and providing relief from pain and numbness, particularly at night. The brace may also be worn during the day to minimize discomfort and allow the tissues within the canal to rest.

Anti-inflammatory medications, such as ibuprofen and aspirin, can help reduce swelling and alleviate symptoms.

Working with a physical or occupational therapist can also be beneficial. Therapists focus on identifying and addressing the root cause of nerve pressure. They may evaluate your workstation, suggest ergonomic adjustments, recommend exercises, and provide guidance on maintaining proper wrist alignment to prevent future issues.

Surgical Treatment

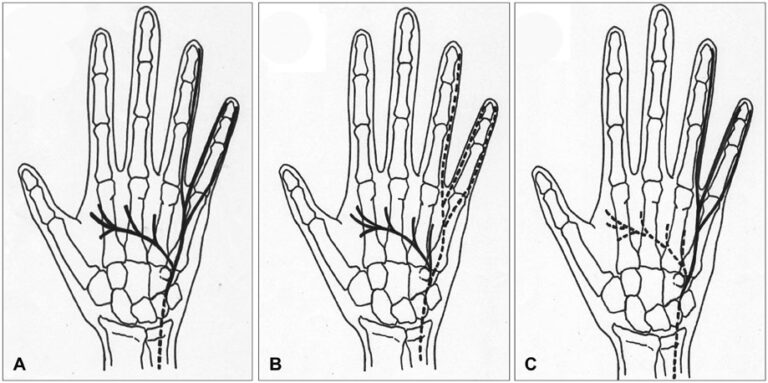

If nonsurgical methods fail to provide relief, surgery may be recommended to reduce pressure on the ulnar nerve.

Surgery can be performed under general anesthesia (putting you to sleep) or regional anesthesia, which numbs only the affected area. Regional options include an axillary block (numbing the arm) or a wrist block (numbing the hand). Alternatively, a local anesthetic like lidocaine may be injected directly into the surgical site.

During the procedure, the surgeon cleans the palm with an antiseptic solution and makes a small incision over Guyon’s canal. This allows the surgeon to access the ligament forming the canal’s roof, which is then carefully released using a scalpel or scissors. Special care is taken to protect the ulnar nerve during this process.

Releasing the ligament relieves pressure on the nerve. The skin is then sutured together, leaving the ligament’s ends separated. Over time, scar tissue forms in the gap, ensuring the ligament no longer compresses the nerve.

This procedure is usually performed on an outpatient basis, meaning you can return home the same day.

Rehabilitation:

What Can You Expect During Rehabilitation?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

If nonsurgical treatments are successful, you can expect noticeable improvements within four to six weeks. During this period, you may need to continue wearing a wrist splint at night to prevent your wrist from curling while you sleep. Focus on maintaining proper body and wrist alignment during daily activities, and avoid repetitive motions, heavy gripping, or placing excessive pressure on your palm.

Post-Surgical Rehabilitation

After surgery, your hand will be wrapped in a bulky dressing. To reduce swelling, elevate your hand above heart level throughout the day and gently move your fingers and thumb periodically. Keep the dressing in place until your follow-up appointment with your surgeon, typically 10 to 14 days after surgery, when the stitches are removed. Avoid getting the stitches wet during this time.

While pain and numbness generally improve shortly after surgery, the incision site may remain tender for several months. Full recovery often takes several months and involves attending occupational or physical therapy sessions for six to eight weeks.

Therapy begins with gentle hand movements and range-of-motion exercises, complemented by techniques such as ice packs, soft-tissue massage, and hands-on stretching to enhance mobility. Once the stitches are removed, you may start light strengthening exercises, such as squeezing and stretching special putty.

As rehabilitation progresses, your therapist will guide you through exercises to strengthen and stabilize the muscles and joints in your hand, as well as improve fine motor skills and dexterity. Some exercises will simulate work tasks or sports activities to help you regain full functionality.

Your therapist will also provide strategies to perform daily tasks without placing unnecessary strain on your hand and wrist. Before completing therapy, you’ll learn preventive techniques to reduce the risk of future problems.