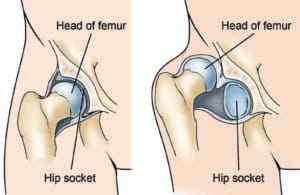

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint where, under normal conditions, the ball-shaped top of the thighbone (femur) sits securely within the socket of the pelvis. However, in infants and young children with developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), this joint does not form correctly. The femoral head becomes loose within the socket, making it prone to dislocation.

DDH is commonly present at birth but can also develop within the first year of life. Studies indicate that infants who are swaddled with their legs straightened and hips tightly bound face a significantly increased risk of developing DDH. As swaddling continues to gain popularity, it’s essential for parents to understand the proper technique to minimize this risk. When swaddling is done incorrectly, it may inadvertently lead to issues like DDH, highlighting the importance of safe swaddling practices.

Description

In all cases of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), the socket, or acetabulum, is too shallow, preventing the thighbone (femur) from fitting securely within the joint. In some instances, the ligaments that stabilize the joint may also be stretched, contributing to varying levels of hip looseness or instability among affected children.

- Dislocated: In the most severe cases, the femoral head is completely dislocated from the socket.

- Dislocatable: Here, the femoral head is positioned within the acetabulum but can be easily pushed out during a physical examination.

- Subluxatable: In milder cases, the femoral head remains loose within the socket. Although it moves within the joint during a physical exam, it does not fully dislocate.

In the U.S., approximately 1 to 2 out of every 1,000 newborns have DDH. Pediatricians routinely screen for DDH during the initial newborn examination and at every subsequent well-baby checkup.

(Left) In a normal hip, the head of the femur fits firmly inside the hip socket. (Right) In severe cases of DDH, the thighbone is completely out of the hip socket (dislocated).

Cause

DDH often has a genetic component, appearing more frequently in certain families. It can occur in one or both hips and affect anyone, though certain groups are at higher risk. The left hip is more commonly affected, and the risk is elevated for:

- Girls

- Firstborns

- Babies born in the breech position, especially those with feet positioned by the shoulders. The American Academy of Pediatrics now advises ultrasound screening for all female infants born breech.

- Those with a family history of DDH (parents or siblings)

- Babies born with oligohydramnios, a condition involving low levels of amniotic fluid

Symptoms

In some cases, babies born with a dislocated hip may not display any visible symptoms initially.

However, it’s important to consult your pediatrician if you observe any of the following in your baby:

- One leg appears shorter than the other

- Uneven skin folds on the thigh

- Reduced mobility or flexibility on one side of the hip

- Signs of difficulty walking, such as limping, toe walking, or a waddling gait

Doctor Examination

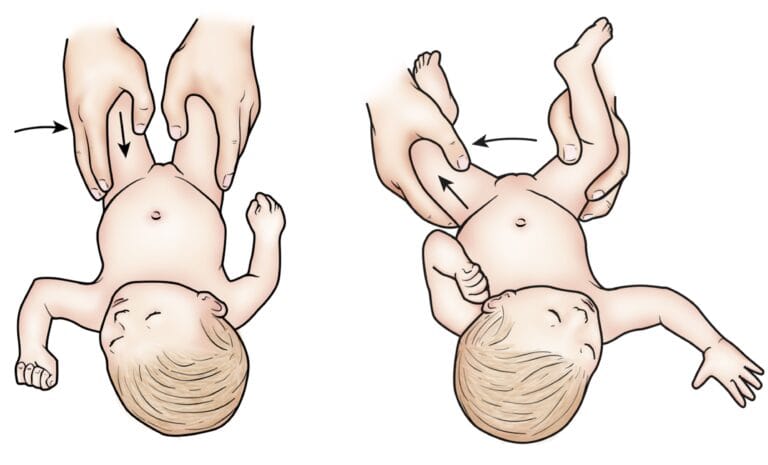

Beyond visible signs, your child’s doctor will conduct a thorough physical examination to assess for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). During this exam, the doctor will feel and listen for any “clunk” sounds or sensations as the hip is moved into different positions. Specific maneuvers are used to check whether the hip can be dislocated or repositioned properly within the socket.

Newborns identified as having a higher risk for DDH often undergo an ultrasound, which produces detailed images of the hip bones. For older infants and children, X-rays may be used to capture clear images of the hip joint structure.

During the exam, your child’s doctor will maneuver your baby’s legs and hips in certain ways to detect hip instability.

Treatment

When DDH is detected at birth, it can typically be corrected with a harness or brace. However, if the condition is not diagnosed until the child starts walking, treatment becomes more complex, and results may be less predictable.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Treatment for DDH varies based on the child’s age and the severity of the condition.

- Newborns: For newborns, a soft positioning device known as a Pavlik harness may be used for 1 to 3 months to keep the thighbone securely in the hip socket. This harness is designed to hold the hip in place while allowing the legs to move freely, making diaper changes easy. The Pavlik harness tightens the ligaments around the joint and supports proper hip socket formation. Parents are essential to the success of this treatment, and healthcare providers will teach them how to handle daily tasks such as diapering, bathing, feeding, and dressing. Regular clinic visits are crucial to monitor the hip and ensure the harness fits properly.

- 1 to 6 Months: Treatment is similar to that for newborns, with the thighbone held in place using a harness or similar device. Even hips that are initially dislocated often respond well to this method. The harness is typically worn full-time for about 6 weeks, followed by part-time wear for an additional 6 weeks. If the harness does not maintain hip positioning, an abduction brace, made of firmer material, may be used.

In some cases, a procedure called closed reduction is needed, in which the doctor gently repositions the thighbone and applies a body cast (spica cast) to keep the bones in place. This is done under anesthesia. Specific guidance on caring for a baby in a spica cast is provided by the healthcare team.

- 6 Months to 2 Years: Older infants may also require closed reduction and spica casting. In some cases, skin traction is applied for a few weeks before repositioning the thighbone. This process, performed at home or in the hospital, helps prepare the soft tissues around the hip for bone repositioning.

Surgical Treatment

- 6 Months to 2 Years: If closed reduction fails to correctly position the thighbone, open surgery becomes necessary. During this procedure, an incision is made in the hip to give the surgeon a clear view of the bones and tissues. Sometimes, the thighbone is shortened to help it fit properly into the socket. X-rays are taken during surgery to confirm the bone alignment, and a spica cast is applied post-surgery to hold the hip in place.

- Older than 2 Years: As some children grow, hip looseness can worsen, particularly as activity levels increase. In these cases, open surgery is often required to realign the hip, followed by the use of a spica cast to secure the hip in the joint.

Newborns may be placed in a Pavlik harness for 1 to 3 months to treat DDH.

Recovery

In children with DDH, a body cast or brace is usually necessary to keep the hip joint stable during healing, with the cast generally worn for 2 to 3 months. The cast may need to be changed periodically, and X-rays and regular follow-ups are essential to monitor recovery until growth is complete.

Complications

Spica casting may cause a temporary delay in walking, but normal walking development resumes once the cast is removed. Positioning devices like the Pavlik harness may cause skin irritation around the straps, and some leg length discrepancy may persist. Rarely, prolonged positioning in the harness may lead to nerve compression in the leg, potentially causing temporary loss of movement. This usually resolves once the harness is adjusted or removed. Though uncommon, blood supply issues to the growth area of the thighbone may affect its growth, and a shallow hip socket may persist, potentially requiring surgery to correct hip anatomy.

Outcomes

With early diagnosis and successful treatment, most children develop normal hip function without limitations. Untreated DDH can result in pain and osteoarthritis by early adulthood, as well as leg length discrepancy and reduced agility. Even with proper treatment, hip deformities or osteoarthritis may arise later in life, especially if treatment begins after age 2.

To support doctors in managing DDH, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) has developed clinical practice guidelines based on research. These recommendations offer guidance but may not apply to every case. For further details, refer to the AAOS’s Plain Language Summary – Clinical Practice Guideline – Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip.