Introduction

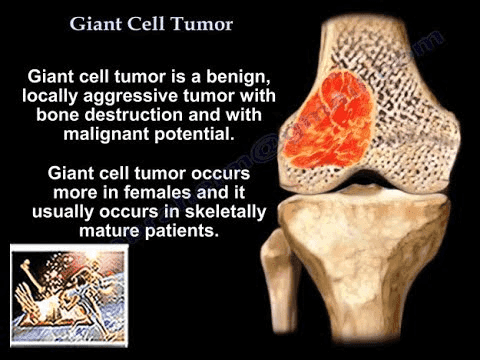

A giant cell tumour of bone is a benign (noncancerous) tumour that can exhibit aggressive behaviour. It grows primarily at the ends of long bones near joints, most commonly at the lower end of the femur or the upper end of the tibia, close to the knee joint. Giant cell tumours predominantly affect young adults, with a slight female predilection, and occur at an incidence of approximately one in a million people annually.

Despite being non cancerous, giant cell tumours can aggressively destroy surrounding bone, necessitating surgical intervention to prevent joint damage.

Description

Giant cell tumours are characterised by their appearance under a microscope, showing numerous large “giant” cells formed by the fusion of several smaller cells. Although many bone conditions feature giant cells, a diagnosis of a giant cell tumour of bone is confirmed when a significant number of these cells are present amidst other abnormal cells.

These tumours typically occur in the epiphysis (the end portion) of long bones, which is unusual as most bone tumours arise in the metaphysis (the flared area near the ends of long bones).

Common sites include:

- Lower end of the femur (thighbone)

- The upper end of the tibia (shinbone)

- Distal radius (wrist)

- Proximal femur (hip)

- Proximal humerus (shoulder)

- Spine and pelvis junction (lower back)

In rare cases, multiple giant cell tumours can manifest in different bones, a condition known as multicentric giant cell tumour of bone.

Giant cell tumours mainly affect individuals aged 20 to 40 and are uncommon in children and adults over 65. Although benign, they can grow rapidly and destructively and, in rare instances, metastasize to the lungs.

Cause

The exact cause of giant cell tumours is unknown. They occur spontaneously without any known association with trauma, environmental factors, or diet, and they are not inherited. Sometimes, they are linked with hyperparathyroidism, a condition involving overactivity of the parathyroid glands.

Symptoms

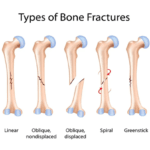

The primary symptom is localised pain, which worsens with joint movement and activity and improves with rest. The pain typically starts as mild but intensifies as the tumour grows. Sudden severe pain may occur if the weakened bone fractures. Some patients may notice a mass or swelling without experiencing pain.

Clinical examination

A thorough physical examination and imaging tests diagnose a giant cell tumour.

Tests

X-ray:

This provides images of dense structures like bone. It shows a destructive (lytic) lesion near a joint, sometimes surrounded by a thin rim of white bone, with possible bone expansion.

MRI/CT Scan:

These scans offer a detailed evaluation of the tumour and surrounding area. A chest CT or X-ray may be performed to check for lung metastasis.

Bone Scan:

This procedure identifies additional lesions by injecting a small amount of radioactive dye, highlighting “hot spots” in areas of abnormal bone activity.

Biopsy:

Confirms the diagnosis by examining a tissue sample from the tumour under a microscope. This procedure can be done with a needle or as a minor surgery.

Treatment

Without treatment, giant cell tumours will continue to grow and destroy bone. Treatment aims to remove the cancer, prevent bone damage, and avoid recurrence.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Radiation Therapy:

Used to shrink tumours in areas where surgery is risky, though it carries a small risk of inducing cancer.

Tumour Embolization:

Blocks the blood supply to the tumour, causing cell death. This procedure is often performed before surgery or as a standalone treatment when surgery is not feasible.

Medication:

Injectable medications targeting specific receptors on giant cells can slow bone breakdown. These medications are used for cases where surgery isn’t possible or for recurrent tumours.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery is the most effective treatment and may include:

Curettage:

Scraping out the tumour with special instruments.

Bone Graft:

Filling the cavity with bone from a donor (allograft) or the patient’s body (autograft), often supplemented with bone cement and additional chemicals like liquid nitrogen, hydrogen peroxide, or phenol to reduce recurrence risk. In some cases, an argon gas laser may be used.

Complex Reconstruction:

For recurrent tumours or extensive bone damage, more complex surgical removal and reconstruction using bone grafts, artificial joints, or a combination may be necessary. The goal is to restore functionality and enable normal activities.

Lung Metastasis Surgery:

In rare cases where the tumour spreads to the lungs, surgical removal of both the bone tumour and the affected lung area is required, typically resulting in a cure.

Outcomes

The outcome depends on age, tumour size, location, and treatment method. Giant cell tumours can recur, so regular follow-up visits with X-rays and chest X-rays are essential for several years post-treatment. Monitoring ensures early detection and management of any recurrence.